The legendary Afropop artist Miriam Makeba wrote unexpectedly joyful sounding songs during the South African apartheid. As apartheid legislation went into effect when Makeba was sixteen, she began identifying as a civil activist against the institutionalized segregation, eventually writing the song Ndodemnyama (Beware, Verwoerd!), a powerful warning song to Hendrick Verwoerd, the white prime minister of what was then the Union of South Africa, and the man considered the architect of apartheid. The lyrics of the song, when translated from isiXhosa, are: Here is the Black man, Verwoerd! Watch out, here is the Black man, Verwoerd!

Makeba was eventually exiled from South Africa. She brought her moral outrage west and redoubled her activism, where she became involved in civil rights and testified in front of the UN against the South African government. Makeba married a founder of the Black Power movement, Kwame Ture, and moved to Guinea where she began writing and performing some of her most explicitly anti-apartheid songs. In 1991, after the fall of apartheid, she returned to South Africa, touring an album she made with Nina Simone, and earning praise from Nelson Mandela. Makeba sang about pain, hope, fear, and anger — and every song was always astoundingly beautiful. Near the end of her life, Makeba said: “people say I sing politics, but what I sing is not politics, it is the truth.”

* * *

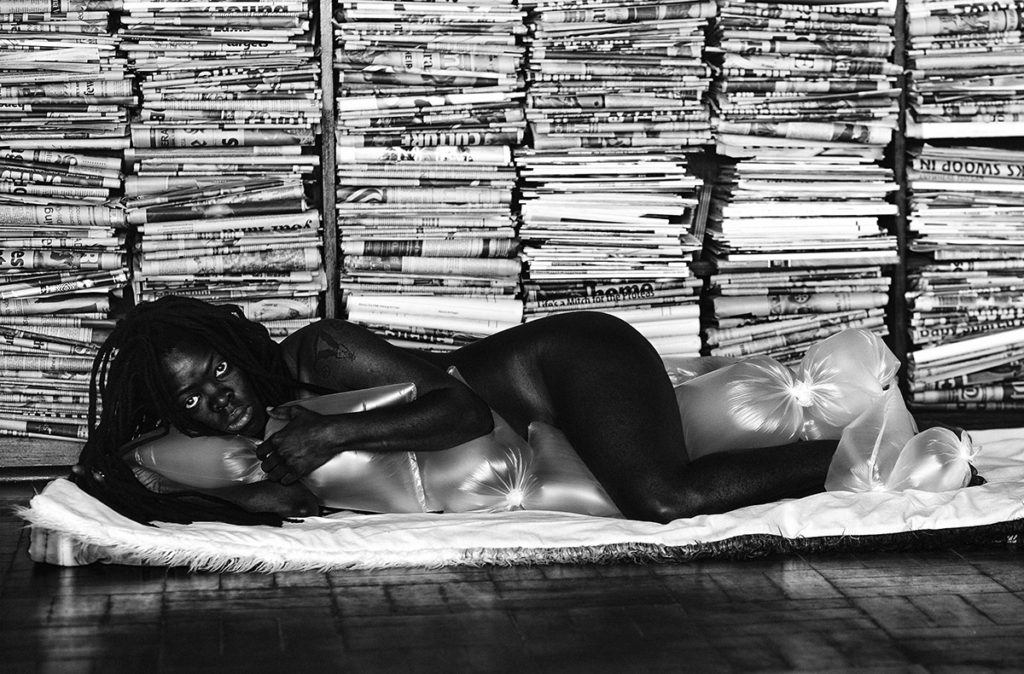

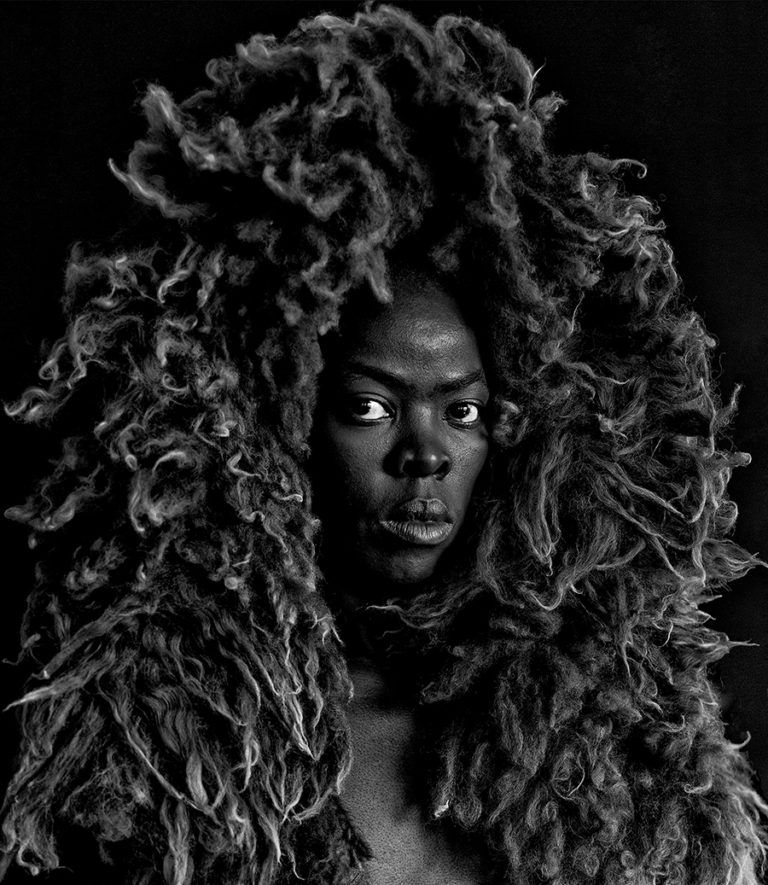

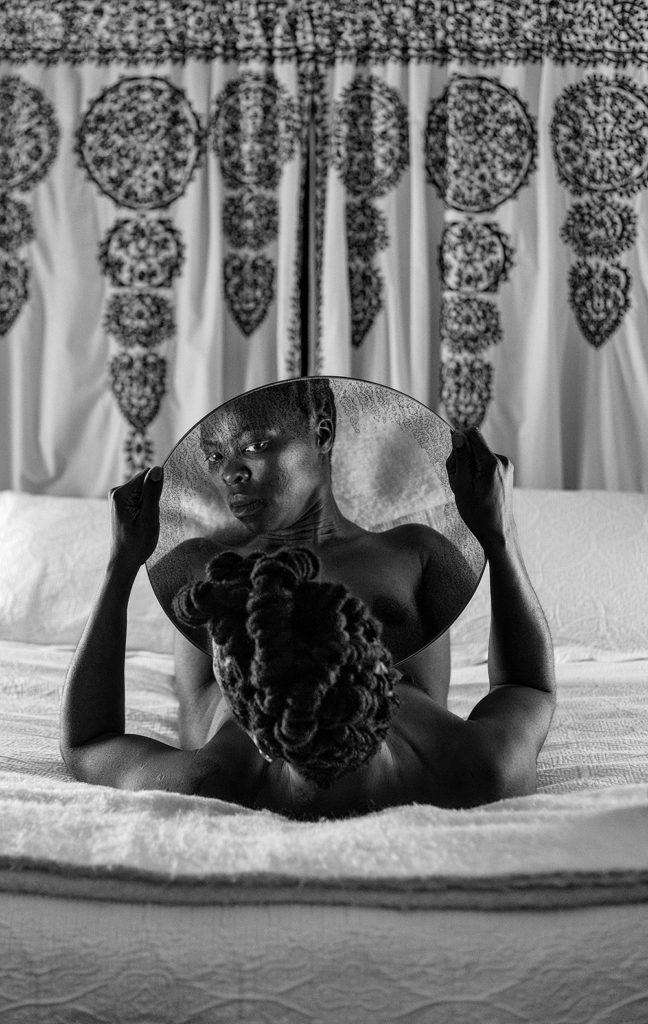

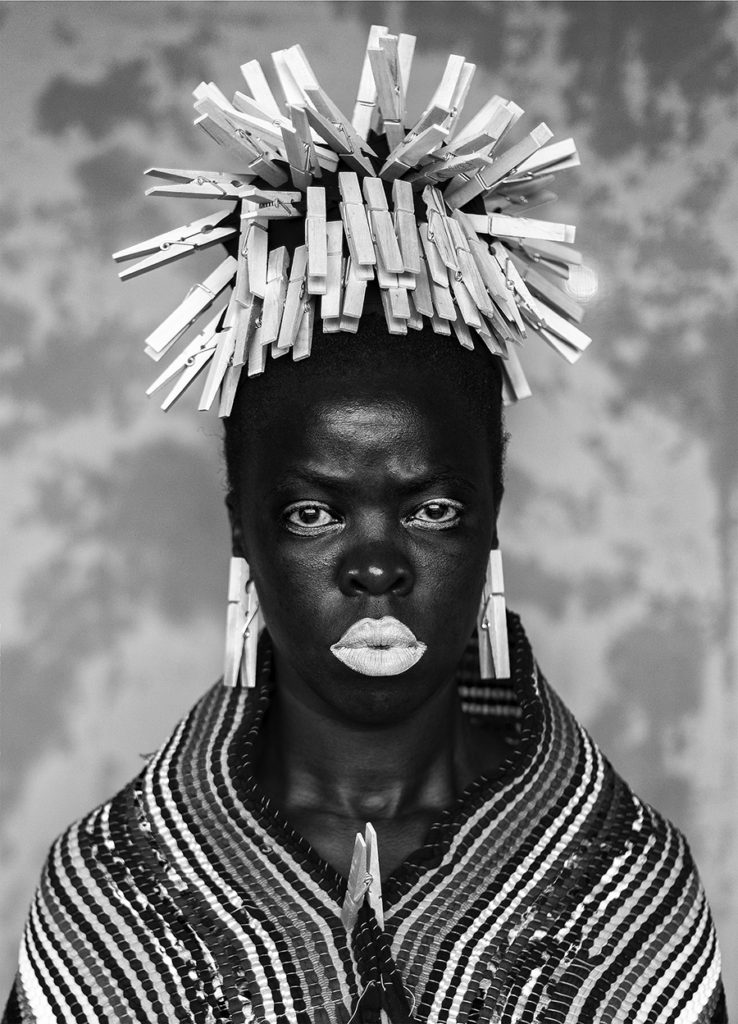

Zanele Muholi’s ongoing project Somnyama Ngonyama (isiZulu for Hail the Dark Lioness) at the Colby College Museum of Art is also political and also exists as truth. There are more than sixty images in the show, all black and white, serialized, and hung salon-style throughout the gallery. Most are traditionally framed but some are massive and applied directly to the wall. Every image is a self portrait and nearly all of them are busts: Muholi appears almost exactly life-size.

Zanele Muholi was born in 1972, at the height of apartheid. They grew up during both South African and American revolutions, the politics of which shaped racial, sexual, and gender identities during a period of raucous instability and a potentially dangerous future. Twenty-one years later, as apartheid was beginning to be repealed, Muholi came of age; their first presidential vote was one that helped ascend Nelson Mandela to power. Legislation that banned discrimination based on sexual orientation started to emerge, and Muholi began making photographs as a mode of activism, an effort to help shift the national (and, for them, eventually international) socialized stigma of queerness and blackness: “That visual narrative wasn’t there in the way that I wanted to see it.” Muholi explains, “It was distorted. It was activism that led me to do the work that I do because LGBTI media representation was so sensationalized and traumatic.”1 Even after the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2006, queerness remains dangerous in post-apartheid South Africa. Inequality based on race, class, gender, and sexuality is still part of the dogma — as it is in America. Muholi’s photographs rewrite that history.

The contemporary use of a camera in activism is largely as a documentary tool. Videos are used in trials and images can still exist as proof. Muholi seems to acknowledge this function of the camera while turning their back on it, using images instead as an aid to performance. There is a parallel of queer photographers and pseudo-documentary images — images that exist between proof of existence and constructed identity. Photographers like Catherine Opie and Ren Hang have explored the hybridity of queer identity and performed reality, working in the space between queer utopia and historic violence. Heteropatriarchal society forces socialized performance among marginalized groups of people as a part of survival, and the images in Somnyama Ngonyama lean into this, acknowledging the inherent performance of all photography and utilizing it as a mirror, reflecting both Muholi’s personal pain and forcing a reconsideration of social binaries. In his seminal book, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, the writer José Esteban Muñoz addresses the ability of art to take “damaging stereotypes and recycl[e] them to create a powerful and seductive site of self-creation.”2

Photographs lend themselves to self-creation and in Somnyama Ngonyama, Muholi does exactly this. One of the largest prints in the show at Colby, Zabo I, Kyoto, Japan (2017) is mounted directly to the wall in a corner of the gallery. The image is barely lit, but intensely contrasted. It shows Muholi standing in the branches of an evergreen tree, the white needles bright against their skin. Out of the darkness of the image Muholi’s eyes seem to fly off the paper with defiance; their expression is somewhere between surprise and confrontation. A quote from Muholi is adhered to the wall nearby, like an artist statement: “I’m reclaiming my blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other. My reality is that I do not mimic being black; it is my skin and the experience of being black is deeply entrenched in me. Just like our ancestors, we live as black people 365 days a year, and we should speak without fear.”

Somnyama Ngonyama feels like an extension of civil rights era activism: unabashed power through aesthetic seduction. In their statement, Muholi says that they aim “to rewrite a Black queer and trans visual history of South Africa for the world to know of our resistance and existence at the height of hate crimes in South Africa and beyond.” This aim to rewrite, to acknowledge and not to cower, is reminiscent of the resurgence of Afrofuturism in pop culture, from Sun Ra to Janelle Monáe and Black Panther. Muholi’s project preceding Somnyama Ngonyama was Faces and Phases, a more traditionally documentary project of lesbian and trans Black women in South Africa. The project consisted of 250 portraits, all similarly lit and composed. Visibility is among the main interests of this work: proof of the existence of queer people and a celebration of their history. The goal of Faces and Phases was reclamation — not of queerness, but of representation. The performance qualities of their subjects are subdued — not ignored, but not confrontational. “I told myself that I would do better than any other outsider to project our lives,” Muholi explains about the project. “Producing an image of a queer being in space? That’s political.”3 The images are strikingly democratizing and empathetic — a quieter contribution to equality and a reaction against the violent history of queer representation in South Africa.

Somnyama Ngonyama is not quiet. Muholi turns the camera on themself, and the work shifts from asking for visibility to performative ownership of identity. As Muholi begins making self portraits, the work also implicates viewer, accusatory and demanding. Any references to violence that were once oblique become specific. Somnyama Ngonyama is made up of hundreds of images and most of them are structurally similar. Understanding the repetition requires attention and forces visibility — any notion of hesitation that may have been present in Muholi’s past projects is gone. This loud change in Muholi’s style seems to have coincided with a worldwide shift toward socio-political frustration where loudness is necessary. Every image in Somnyama Ngonyama is confrontational — nearly every pair of eyes are looking directly into the camera lens.

Other than themself, the signifiers in the images of Somnyama Ngonyama are careful, sparse, and emotional. Muholi photographs in locations that have a personal meaning for them—like a Charlottesville, Virginia, hotel room, or the backyard of their Johannesburg home — and looks for meaningful objects there to adorn themself with. One of the most alarming images in Somnyama Ngonyama is Basizeni XI, Cassilhaus, North Carolina (2016). We see Muholi looking weary and many years older than their actual age. (Basizeni is the name of Muholi’s late sister.) Their gaze is blank, and the background of the image is blown out by a shallow depth of field. A quick read of the photograph depicts someone dressed in traditionally feminine Zulu clothing, but even an extra moment with it reveals much more — what first reads as clothing is actually coiled bicycle tire tubes draped around their neck and body. During apartheid, communities would sometime engage in what was later dubbed “necklacing,” the practice of execution and torture of pro-apartheid enemies by filling rubber tire tubes with gasoline, wrapping them around the accused, and lighting them on fire. Muholi’s image references such a horrific act of violence inexplicitly, but it doesn’t feel guarded. Instead, it feels shameless, courageous, and deeply sad.

Muholi’s images don’t always engage in such darkness. Their intent is so grounded in optimism and gratitude for their own survival, the deep love they have for their subjects, and pride. They want those who they photograph (be that others or themself) to look good, to feel proud of their photograph and for their image to be a document of that pride. During an interview in 2018, Muholi says “ I photograph myself to remind myself that I exist.”4 This refusal to accept an identity on anyone else’s terms other than their own — despite millennia of historical genocide, violence, and marginalization of queer people of color in all societies — is striking and immutable. Their images function as a narrative reclamation, but not outright celebration. Miriam Makeba’s quote — “people say I sing politics, but what I sing is not politics, it is the truth” — continues to ring throughout the show; it’s exciting to see Muholi’s images as nothing but truth.

Just as Makeba used beautiful songwriting to cloak her powerfully radical views of apartheid, Muholi uses their craft with careful intent. Beauty is intentional and cleverly manipulative in their work. The history that Muholi attempts to rewrite in Somnyama Ngonyama is not a pretty one, but the prints at the Colby are beautiful — they demand engagement. It’s hard not to compare compositions and find metaphors before suddenly standing still and falling deep into the velvet textures of a ten-foot-tall -print. This subversion mimics Muholi’s efforts as an activist. The show at Colby Museum lands in between gratefulness and anger, rewritten pasts and hopeful future, tenderness and assertion. There is almost no paper-white in these photographs other than Muholi’s eyes — they’re hard to look away from.

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, curated by Renée Mussai, is on view at Colby College Museum of Art from February 14–June 9, 2019, as part of a tour organized by Autograph London.

Colby College Museum of Art

5600 Mayflower Hill, Waterville, ME | 207-859-5600

Open Tuesday–Saturday 10am–5pm, and Sunday 12–5pm. Free.

- Raquel Willis, “Zanele Muholi Forever Changed the Image of Black Queer South Africans,” Out.com, April 23, 2019. ↩

- José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 4. ↩

- Art21, “Zanele Muholi in ‘Johannesburg’,” Art in the Twenty-First Century: Season 9, video, September 21, 2018. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Dylan Hausthor is a photographer, filmmaker, and editor based on a small island off the coast of Maine. His work is an act of hybridity–an effort to render field recordings into myth. Interested in small-town gossip and the fragility of journalistic truth, his work examines the borders between autobiography, fiction, and fact. Hausthor’s work has been showcased nationally and internationally by the Aperture Foundation, Ain’t-Bad, PHMuseum, Humble Arts, Nava Print Studio, Gomma, Yogurt Magazine, Void, and LensCulture. He founded Wilt Press in the spring of 2015 and is a current grantee and previous artist-in-residence at the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation in Rockland, Maine.