Gordon Hall | In my late teens I had two near-death experiences within a couple of months of each other—an illness and then a car accident. After recovering from both, I didn’t really know what to think about them, except for a general gratefulness to be alive and a vague fear that maybe I actually wasn’t. Mostly I just got back to life as quickly as I could. The following summer was when the sadness hit, and I spent a lot of time walking around the Christian Science reflecting pool in Boston and crying. I was staying at my parents’ house, and during this time I took on the project of fixing up a room in their house that I would stay in when I visited. I painted this room in stripes of different shades of off-white. Each paint color I chose looked white in the can, but when put next to each other on the wall appeared pink and yellow and green and blue. And the stripes were of varying widths and each had to be taped off separately. The effect was a sort of luminous pastel glow in the room, produced by the proximity of these bands of very similar but distinct shades. The project took weeks, and my commitment to it was intense, somehow not processing the impracticality of such a time-consuming undertaking on a room I was barely going to be living in. Now, looking back at this, I think that this painting project was directly related to my recent proximity to the possibility of my own death. To pour out my energy and time on something so unnecessary was actually a declaration of connection to a world from which I had been disconnecting. Telling it—myself?—that I do care about it, that I don’t want to leave yet, that I’m not ready. Sometimes I think that this home decoration project was the beginning of a way of making things in response to the threat of oblivion which is central to my work as an artist even now, twenty years later. There are numerous resonances between our ways of making, but this is one of the most central ones—the links between object-making and death.

Elizabeth Atterbury | Yes, this is a big point of connection in our work. For me, it was the experience of losing someone very close to me. My mom died when I was 15. Like you, I got right back to life. A year later, the unbearable weight of grief arrived. My version of painting the walls was writing. I used it to dig myself out and make sense of things. This is not so different from how I work now. The looping cycle of disorientation and clarity in the studio. My interest in writing shifted to photography. I was curious about the blur between life and death and I tried to make pictures about this in-between state. I also wanted to understand death through the eyes of my aging grandfather, who had lost his only child and wife and was near the end of his life. When my grandfather died, my sister and I packed up his apartment. We easily got rid of the unfamiliar, new furniture and home goods that he acquired in the last years of his life, but we took our time with everything else. We sifted through his letters and boxes, closets and drawers. Our grandmother had passed years earlier, and our grandfather had moved to a different apartment in a different town. He brought much of our grandmother’s belongings with him—her dresses and shoes, her purses, her glasses. He unpacked her things, hung up her coats, put her perfume and comb in the medicine cabinet. I asked him about this once and why he did this and he said something to the effect of “so she knows where to find everything.”

GH | So she can find them?

EA | Yes. And then, countering what he had just said, he added that being surrounded by her things brought him comfort. We moved my grandfather’s belongings into a storage locker where most of my mom’s things lived, save for a handful of treasured objects from her house that never went into storage. One of these objects is a ceramic peanut that she brought back for me after a work trip when I was 9 or 10. The shell is glazed a light sandy color and has a bottom and a lid. Inside are two peanuts painted brown like the papery skin. I can remember lifting the lid off and carefully removing the nuts, either getting my fingers around them one at a time or tipping the bottom upside down into my hand, which revealed the crude bottoms, unglazed and cracked around the opening of the cavities. I would often go over to the shelf where the peanut sat and lift the lid off to look inside, and I remember always feeling the satisfaction and surprise of what was inside. This is true even now. I think this peanut was one of the first objects I really fell in love with. Last fall, I started making my own versions.

GH | Why do you think now is the time you are finally returning to your peanut, placing the enlarged replica of it here on this table with your other small objects?

EA | Maybe I am returning to it now because of the part of my life I’ve entered. I keep thinking about my mom and her two children, and me and my two young kids now. Two forms held by one. And then to think that my kids were inside my mother’s body too, as eggs, inside my body, inside her womb. Another layer of nesting. I wanted to make the piece so I could experience looking at this object again. Remaking an existing form means I come to understand it in a different way. The peanut is still so captivating, after all these years always on display alongside other important possessions in every place I’ve lived. I guess I wanted to put it into a new arrangement, a new set of relations. In the last few years, I have been appropriating and remaking forms that exist in my world—a tennis court, an eraser shield, a clothespin spring, the base of a sandal to list a few. The peanut is part of this same family of objects—forms that both carry a specific meaning and in their remaking undergo a change for me, becoming more known and more mysterious at the same time.

GH | How can they be both more known and more mysterious to you? Aren’t these opposites?

EA | I know it sounds contradictory, but when I remake an object that I am so familiar with I simultaneously get to know it better, through studying it so closely to replicate it, and I am also meeting it for the first time, since it is now new to me and entering into the world in a different way.

GH | We are having this conversation in the peak of the second wave of the COVID 19 pandemic in the US which kills more than 3,000 people each day. A number like this is hard to know what to do with, how to imagine it, to feel its weight. When I think about people’s personal possessions, though—their clothes and shoes and books—I think about 3,000 families every day beginning the process of figuring out what to do with these things. What to throw away and what to keep. The feeling of erasing someone’s material presence after they are gone. That stillness of objects in a now lifeless room. I keep thinking about the term “still life”—the history of death in still life painting—symbolically and literally in the form of dead animals, formerly living things becoming one of many objects on a table, with a jug, a book, an orange. Perhaps there is a link here to the photographic way you arrange your small objects on surfaces. Is it possible to call these still lifes? And is there a link here between the still life and the presence of mortality in your work?

EA | First, to your point about COVID and grieving: to accept this level of mass loss is more than most of us can handle. The fact that people are dying alone, without loved ones. The fact that loved ones are grieving alone, without community or rituals of gathering. It’s so sad and wrong. We already have a messed up relationship with death—the idea of it, the process of it—and so to add more restrictions, which, I know, from a public health perspective are necessary…it harmfully compartmentalizes a process which is meant to be porous and without restrictions. I heard a story on the radio about a woman who took a job in the laundry room at her mother’s nursing home so that she could be there when she died. And she was.

Our conversation has brought up something I hadn’t thought of until now which is the extent to which I go in and out of grieving for people dear to me, who are alive but for whom I cannot see. It is a strange feeling. It is the feeling you hope for when someone actually dies, which is: maybe they are still alive but for now they are somewhere else. Eventually, they will return.

But to answer your question. Yes, I think it’s possible to call my arrangements still lifes in the very basic sense that they are objects placed with intention on a surface. When I’m making my work, however, I’m not thinking about still life painting but of different types of object arrangements—both domestic or institutional—deliberately or unconsciously configured. Is each object that I make charged with significance and metaphor for me? Yes. When I arrange individual forms on a surface into an ensemble, am I doing so with the expectation that you will be able to read my metaphors with any level of fluency? No. The individual pieces are created with specific purpose but the arrangement of them is more an act of trust (and hope) that the forms will tell me something previously unknown through their collectivity as a group, rather than tell you, the viewer, something that I already know. These small sculptures are souvenirs, from living, I suppose, in all their triviality and significance.

GH | It sounds to me like you are arranging a sort of memorial through the ritual of making and remaking these objects.

EA | That’s very plausible. A sort of choreography of forms, like how objects are arranged on altars. I often think about an arrangement of forms as a picture, with a primary vantage point. Even last night, when I woke up and couldn’t fall back asleep, my mind drifted to our conversation and then to thinking about the arrangement of bodies on the bed. My husband, straight and tight against one edge; my son, crooked along the top of the bed, head under a pillow; my daughter, a small hyphen in the middle of the mattress; and me, my body snaking around my daughter and the cat, tucked behind my knees. I thought of this arrangement not from my tangled, immersed perspective, but from above.

GH | You are both inside and outside. Participating but also looking at.

EA | I’ve always been a looker, even a snooper. I just want to see everything. I always looked through all of my parents’ stuff. This emphasis on looking brought me into sculpture in the first place. Initially, I made sculptures explicitly to photograph—ephemeral props for the camera. Gradually these props declared themselves more as objects, documented by but not really transformed by the camera. At the same time, I was looking at images of artifacts, hierarchically placed into specific configurations that made for a beautiful picture of forms. This drew my attention to all the ways we move things around into arrangements for looking. Unselfconsciously on a dresser top, inside a suitcase, or on a cluttered window sill. Or intentionally like in a museum vitrine. These various modes of looking at arrangements of things.

GH | In one of our studio visits you mentioned something that has stuck with me about your approach to arranging objects. We were talking about your love of museum displays of ancient artifacts, like the vitrines in the ancient wing at the Met. I was asking you a bunch of research-oriented questions—what are these things, what were they for, who made them, and so on. And you responded, maybe a little timidly, that the answers to those questions are not a focus for you, that maybe they should be, but that in some way it would be unhelpful for you to know them, because it would fix the objects’ meanings in the world of facts and prevent you from experiencing their full mystery as forms. There is a tension here that I think is central to your work: an engagement with specific personal and historical meanings alongside your investment in not-knowing, a certain kind of opacity that allows for intense visual observation. Am I articulating this correctly?

EA | Yes. In the case of museum displays and artifacts, it is my attraction to the form and not my curiosity to learn its function that draws me in. As you mention, the not-knowing makes for a different experience of looking. My chosen state of not-knowing extends to objects familiar to me. Recently, a friend was in the studio looking at the table top sculptures in Letters and Souvenirs. She asked about my wooden remake of a red paper wall stencil that hung in my grandparents’ apartment. It is a circle with scalloped edges. Inside the circle are straight and curved and intersecting lines that make up a Chinese character. What does it mean, she asked. I said I didn’t know but probably something along the lines of Good Fortune or Happiness. She asked if I was at all curious to know and I said I wasn’t. For me, the ornament is a relic from my memories of weekly dinners at my grandparents. Hanging over the front door, the form was the size of a clock and I would stare at it as if counting minutes and seconds, listening to my mom and grandparents converse in a language I didn’t understand. This is what I mean about something being both deeply personal and unfamiliar, even unknowable. I love thinking about how an object has a life of its own. The gap between what it means for us and what it could possibly become, beyond us.

GH | Does this interest in “not-knowing looking” apply to your arranging of the copper plates in the scrolls? These are the first ones you have made that are monochromes, correct?

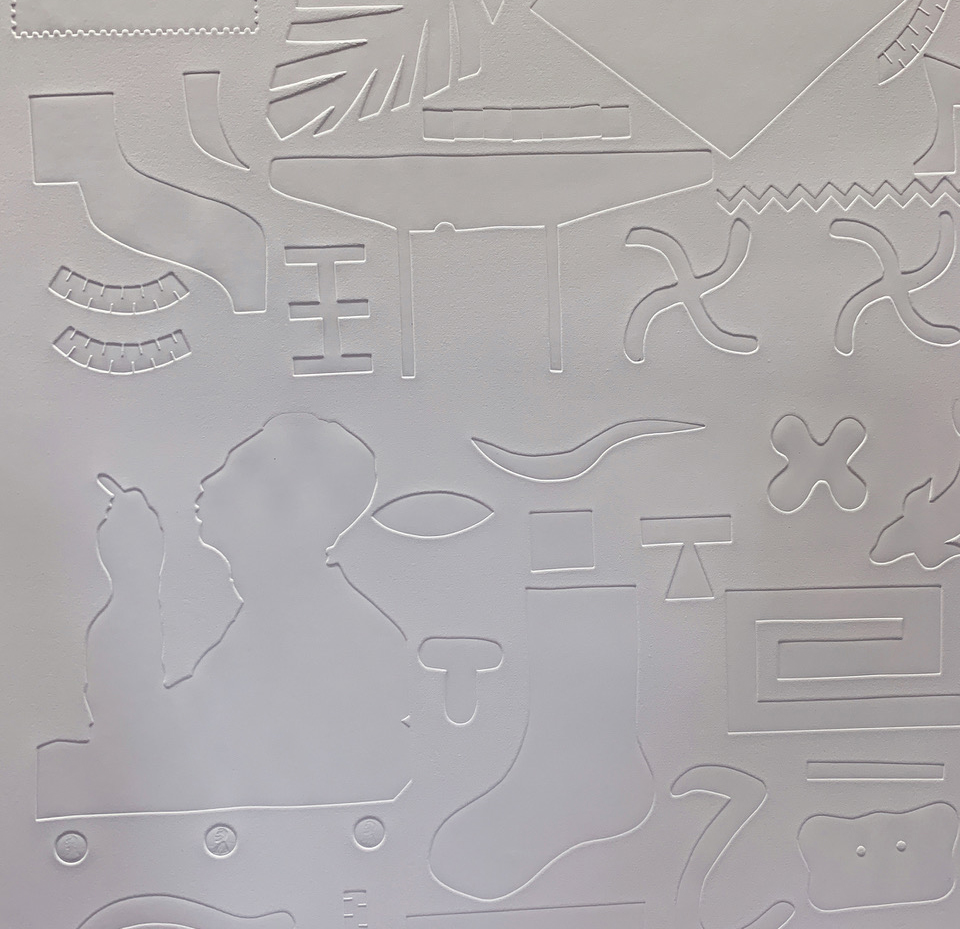

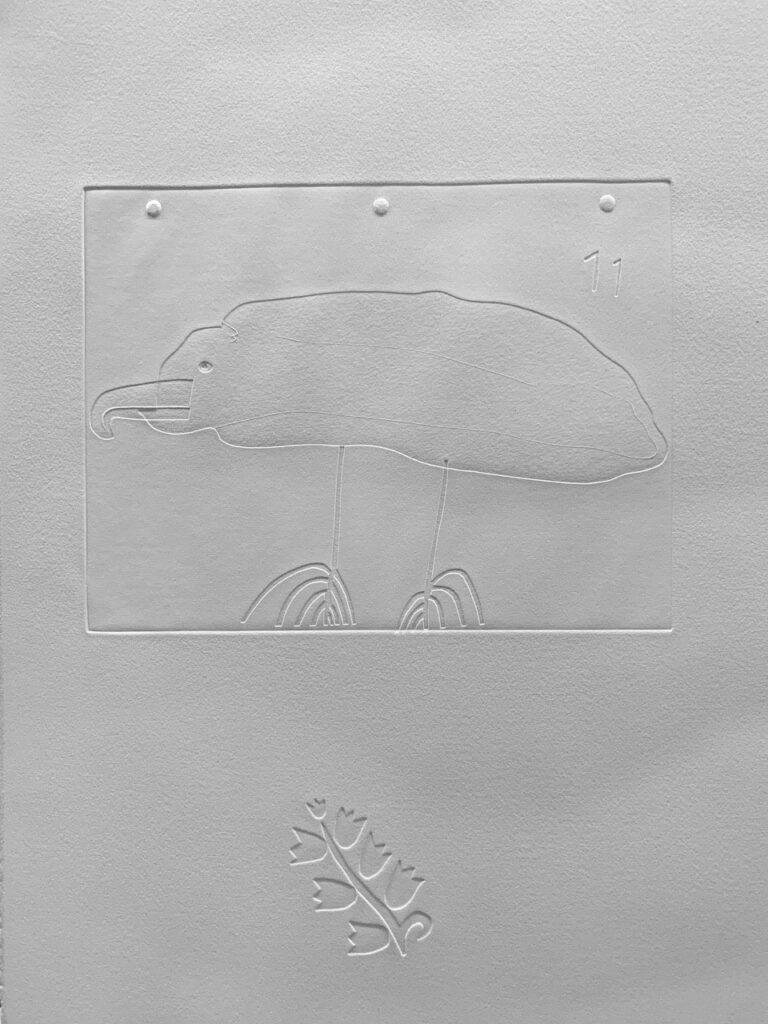

EA | For anyone looking at the prints, there will be recognizable shapes—tube socks, cherries, jacks, a skeleton key, postage stamps, letters from the alphabet. For anyone acquainted with my work, there will also be familiar forms associated with other work of mine. And for anyone viewing the scrolls in person, at the show, there will be forms in the prints that exist elsewhere in the gallery. In all instances, though, there will also be forms unknown and unlearnable.

My work is visually very formal and I think it has a politics to it as well. But I reach both of these places through autobiography. I start with the forms in my own life. This is important to me even though I often don’t reveal the personal origins of my objects. The copper plates are probably the most explicit place where I reference my life—a catalog of over 200 shapes that largely speak to my small world, materially and emotionally. The plates are words, ideas, characters, people, and quite literally the negative space between these shapes.

GH | Your work puts us in the position of un-knowing in relation to your life, just as you want to be in the position of unknowing in relation to historical artifacts.

EA | Yes. I’ve never thought about it this way. Maybe I am trying to recreate that experience of viewership. These scrolls were made over the last ten months and I think of them very much as an archive of my life during COVID, particularly during the spring and summer. They are the letters of Letters and Souvenirs. And yes, these are the first prints I have made where the copper plate embossments are shown alone, as opposed to as a layer in combination with colorful chine collé. There is no ink or additional collaged paper, only the impressions made by the plates. In these prints, I also made single-use paper plates. This is how I translated and incorporated a number of my son’s drawings into the prints.

GH | I’m still thinking about how a moment ago you described finding places to put your mother’s possessions in your own home. Giving them new spots to live, on your shelf, surrounded by your own things. I feel like you are doing something similar in the studio—remaking and combining souvenirs from your life in a way that both memorializes what has been but also changes it, turns it into something different. A kind of formal metabolizing that ensures that life continues to unfold and that meanings don’t get permanently fixed.

EA | I need to remember things but I also need to keep the future open. Just because an object lived one life doesn’t mean it cannot live another.

This interview was commissioned by The Chart with support from the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation. Elizabeth Atterbury’s exhibition, Letters and Souvenirs, is on view at DOCUMENT from January 8 through February 20, 2021. You can learn more about the show and read an additional text on Atterbury’s work by Anna Hepler at DOCUMENT’s website.

DOCUMENT

1709 w Chicago Ave, Chicago, IL | 312.535.4555

Open Tuesday–Saturday 11am–6pm or by appointment

Gordon Hall is a sculptor, performance-maker, and writer based in New York. Hall has presented solo exhibitions at EMPAC (2014), Foxy Production (2014), Temple Contemporary (2016), The Renaissance Society (2018), MIT List Visual Arts Center (2018), and Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (2019). Hall’s sculptures and performances have been exhibited in a variety of group settings including Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2010), SculptureCenter (2012), Movement Research (2012), Brooklyn Museum (2014), White Columns (2015), Whitney Museum of American Art (2015), Hessel Museum at Bard College (2015), Chapter NY (2015), Art in General (2016), Wysing Arts Centre (2017), Abrons Arts Center (2017), Socrates Sculpture Park (2017), The Drawing Center (2018), David Zwirner New York (2018), and the Verge Center for the Arts (2019). Hall has organized lecture-performance programs at MoMA PS1(2012), Recess (2013, 2014), The Shandaken Project at Storm King Art Center (yearly, 2012 -2016), Interstate Projects (2017), Brooklyn Academy of Music (2017), Artists Space (2020), RISD Museum (2020), and at the Whitney Museum of American Art, producing a series of lectures and seminars in conjunction with the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Hall’s books include Reading Things—Gordon Hall on Gender, Sculpture, and Relearning How To See (Walker Art Center, 2016), AND PER SE AND (Art in General, 2016), Details (Walls Divide Press, 2017), The Number of Inches Between Them (MIT, Printed Matter, 2019), and OVER-BELIEFS, Gordon Hall Collected Writing 2011-2018 (Portland Institute for Contemporary Art/Container Corps, 2019). Hall’s work has been covered in Artforum, Artsy, Art in America, V Magazine, Randy, Bomb, Flash Art, Title Magazine, and Mousse Magazine, and they have published essays in Theorizing Visual Studies (Routledge, 2012), Art Journal (2013), What About Power? Inquiries Into Contemporary Sculpture (SculptureCenter/Black Dog Press, 2015), Documents of Contemporary Art: Queer (Whitechapel/MIT Press, 2016), and Art in America (2018), among many other contexts. Hall has been awarded residencies and grants from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Triangle Arts Association, The Edward F. Albee Foundation, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ACRE, Fire Island Artist Residency, and Foundation for Contemporary Arts. Hall holds an MFA and an MA in Visual and Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA from Hampshire College. Hall was a 2019-2020 Provost Teaching Fellow in the Department of Sculpture at Rhode Island School of Design and will be resident faculty at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in the summer of 2021.

Gordon Hall is represented by DOCUMENT.