by Myron M. Beasley

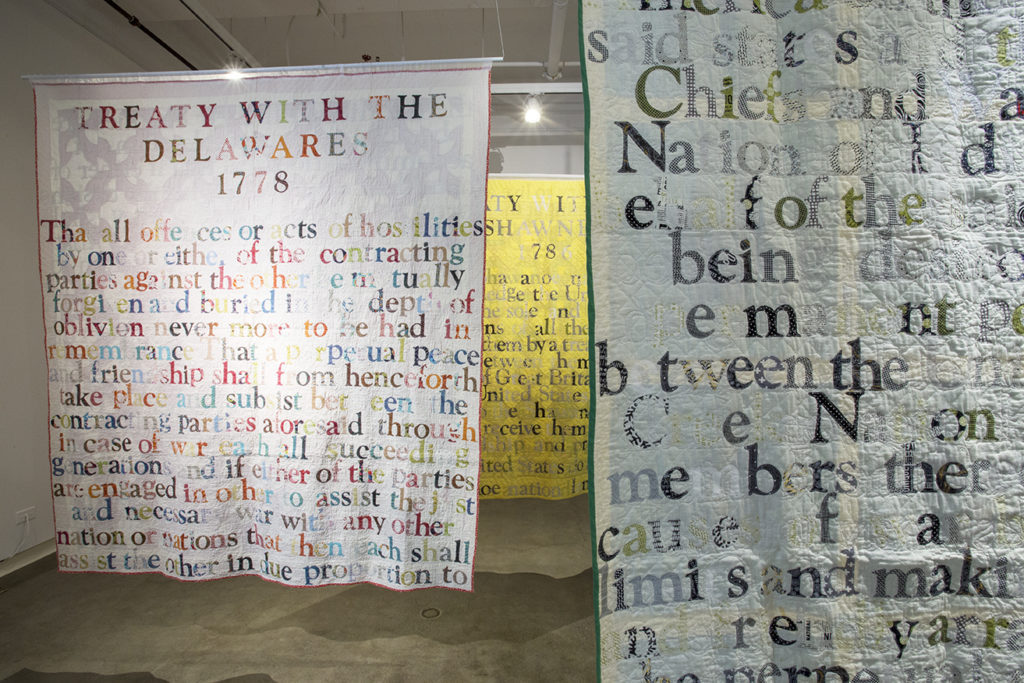

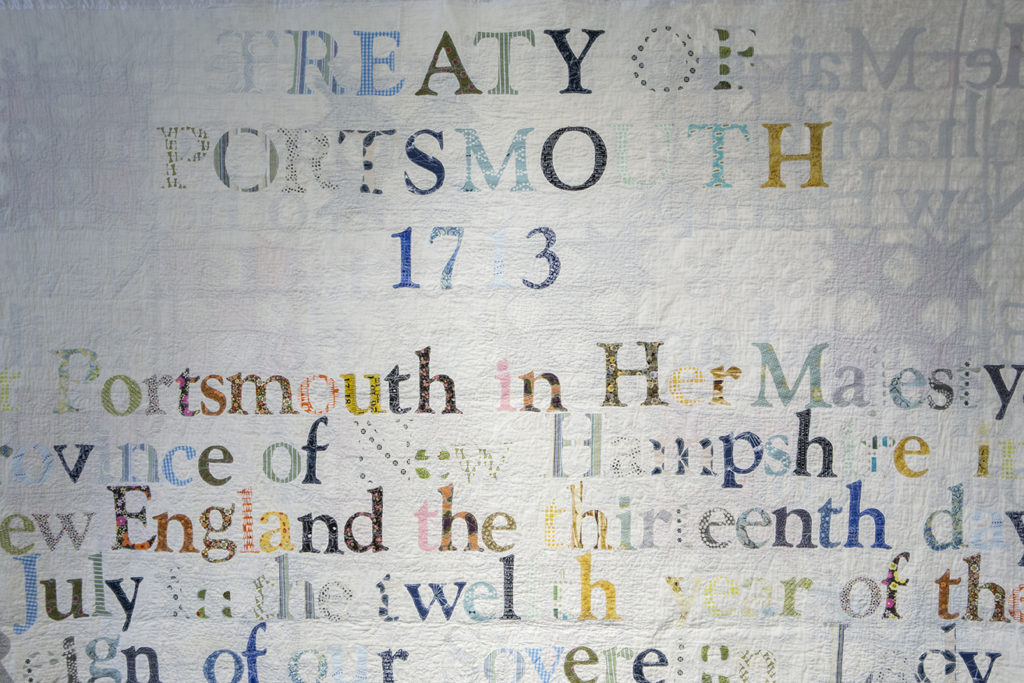

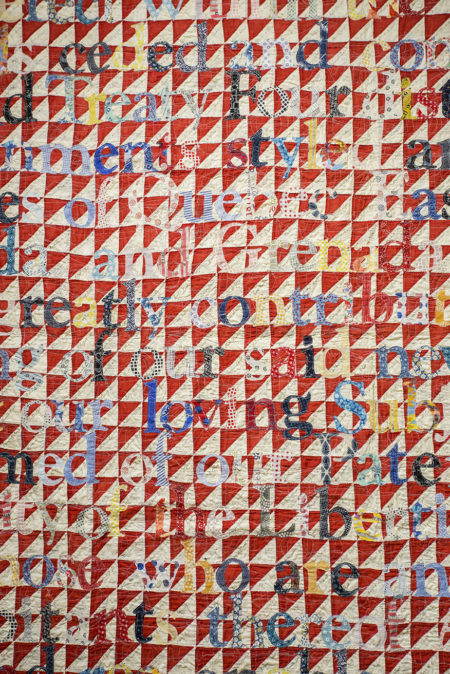

My interview with Gina Adams took place October 2018. She admitted that she was on a forced one-month respite having been on deadlines since 2015. We discussed her three-month artist residency in the studio art department at Dartmouth, with an exhibit in the Jaffe-Friede Gallery. The Dartmouth residency was one of several recent high profile endeavors, including the 2018 Portland Museum of Art Biennial, that speaks of her prolific and profound body of work. Adams’ Broken Treaty Quilts are a project in which she inscribes text of the disingenuous concordats between the white man and the indigenous communities of the United States on calico quilts. The project, like the object of the quilt itself, performs a polyvocality with each stratum: from the stitching, the weaved fiber, patterned fabric, joining the appliqué — not to mention the act of quilting which is piercing through the multiple layers with thread as a mucilage, holding the various elements together to create a tableau — for function and often aesthetic. I situate Adams in the panoply of contemporary living artists who speak succinctly and creatively, to the persistent and nuanced discourses of colonization. The use of the quilt, an everyday-use object associated with the art of making do, Adams flips into a critical performance to interrogate and deconstruct American history. Our wide-ranging interview touched many on of three broad themes: ritual, archive, and storytelling. Below are excerpts from the interview.

Myron M. Beasley | I’ve read a lot of the interviews that you’ve done and several pieces that’ve been written about your quilts and you. Gina, I am interested in a couple of areas, such as the concept of ritual and storytelling in your work. Also, how can we view your work as an archive? I ponder contemporary scholarship happening in archival studies that makes us rethink what an archive is and what nuanced ways of archiving are. Therefore it is challenging the mere epistemology of how we think about objects and things. However, first, can you begin with your quilting history, who taught you how to quilt?

Gina Adams | My earliest memories are having a needle and thread and sitting underneath my mother while she was sewing. Moreover, she would be passing down scraps to me, and I would be stitching them together. Well, now, my sons — actually my oldest son was a little bit more interested in it than my younger son. I didn’t force it upon them, but they were always around when I was sewing and making things. My oldest son still wants to make things when he comes to visit or when I’m there.

MB | And how might that practice of stitching be considered ritual for you?

GA | I study a lot of ritual and performance; [in school at Maine College of Art] I took a class on the topic of African divination, in which we explored how some African-based faiths culturally look at ritual and performance and textiles. It was transformative for me — eye-opening. I consider it to be almost like going to therapy when you start opening up, you’re peeling these layers of an onion. The times of greatest communication in my family history has always been around textiles.

MB | Interesting. So, would you tell me about that?

GA | I grew up in a blended family. My mother had three children and my father had five children from a former [partner]. However, my mother was the middle of nine and my father was the oldest of fourteen from Southern Maine. I am a fourth-generation quilt maker: my mother, my aunt, my grandmother, my great-grandmother are all quilt makers to different varying degrees.

It was my mother’s sister who taught me my first color theory lesson. I was around 13. She had been teaching me quilt making starting with small squares of appliqué to hand stitch. I went like every Tuesday or Wednesday after school, and I stayed there till after dinner. I would learn the different patterns and stitches from her. It was also that same year when I was 13 years old when she took me to a quilt shop, and we picked out the entire fabric for the quilt I wanted to make. She walked me through how to look at the color of the fiber, what to think about how it was printed, how different patterns and textures went together. My aunt was not college-educated, but she’s probably made several hundred quilts in her lifetime, and her house is like a museum of them. I can remember so fondly the times working with her. When we finish a quilt, the whole community will come together — quilt makers who were in her quilt circle. I was the youngest one, and we would sit around the quilts and be hand quilting. My grandmother was also involved, and elders in the community were involved, and it was wonderful. So, for me, when I reflect on my own identity, particularly when I am engaging with the native community, I always think in the dyad: ritual as outsider, ritual as insider.

MB | How so? Cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s discussion of identity is that it is always moving and always negotiated. Are you suggesting that you liken the construction of your quilts to the mediation of your identity?

GA | I think of it as a special division of colonizer and assimilated. I’m always placing myself in such a dyad. However, as far as native ritual, there is a lot of it to which I will always be a ritual outsider because of assimilation, because of forced assimilation to boarding school, and family history that I know when I go to powwows. I’m an insider with my language; I’m an outsider at a powwow. When I’m there, I always feel like, do I fit in? There are always reminders that I am assimilated, and that’s — that’s not a bad thing. It is an important history to recognize and respect.

I have a solid understanding of what archivists do from a museum perspective, and I’ve studied it quite a bit. There’s always a disconnect with how they (museums) treat indigenous materials because they are living objects that are connected to ancestor and ancestry. Moreover, they speak to you, and this is something that many people don’t understand. I felt it completely — I felt a complete connection when I was a Smithsonian artist research fellow. I was in the archives, and the objects were singing, and I was singing back, and it was just moving.

I am reminded of the artist Jeffrey Gibson. I love the video series he created with ancestors of archives, living objects, and the conversation that was recorded between the living ancestor and the pieces that are being held in archives. It brought me to complete tears, and it was healing, these things are healing and essential to share. So, in my work, I’m always thinking about how can I share the knowledge of the living objects without being perceived as odd? You have to have these layers because some people find it hard to understand. Also, I think mainly about spiritual and abstract art.

MB | I want to ponder of the concept of the archive. Alternatively, perhaps I should use the word objects in this context. I appreciate that you consider the objects as living and are endowed with power. I want to connect this concept of things with power and living with your construction and use of quilts. I think of Verne Harris (the personal archivist of Nelson Mandela) who writes passionately about objects, memory and social justice. Your quilts are objects — living objects — that recall a history of both injustice and genocide.

Now, what struck me — and this is also related to ritual — was a clue that I read that you said how this thing made you connect with your ancestors and your family, right? “It is interesting when the negotiation of the space becomes a performance.” At your show at Dartmouth, you engaged the community by offering public letter-cutting sessions. The engaged practice is in a tradition of the sewing rebellions made famous by artists Frau Fiber (aka Carol Francis Lung) and Steven Frost. You invited individual people to come to the letter cutting sessions at Dartmouth. How did this endeavor impact your artmaking and articulating your art practice to a range of people?

GA | After the opening, the gallery director, Jerry Hopkins, informed me that space down the hall was free. It is a rotunda-type structure that is surrounded by windows. I’ve been wanting to do this open letter-cutting session where I would have a space to invite the public. I came with a letter-cutting kit, they provided tables, and I was set to go. The first week was a little bit slow. I quickly discovered that some people were coming in because they were just interested in what I was doing. They hadn’t even seen the exhibit, which was 100 yards away. Some brought their children who had gone to the show and read the statement, and read the quilts and the treaties. The kids were mesmerized by the fabric, and they just wanted to cut. I did this every single day for two months and each day would be completely different. During the first week, I had different people who came, who then returned every single week for the entire two months. It got to the point that people would email me and say I can’t come during the open sessions today.

MB | I want to return to the meaning of things. You touched on the epistemological differences in ways in which indigenous or non-European communities think of objects and the nature of things. You mentioned speaking to objects. I understand and appreciate your use of and drawing from the history of the Calico fabric. What about the energy and spirit of the quilts you use as you tend to work with used and antique quilts. I also think of the women of Gee’s Bend Collective. I spent time with the women two years ago while I was serving as a visiting professor at a college in Alabama. Perhaps you had the opportunity to see the recent exhibition at The Met? Primarily, they speak to me more about the de Certeau concept of the art of making-do. The creative making is about survival and cultural politics.

GA | They’re incredible. I first witnessed the quilts of Gee’s Bend at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts when I was a student at MECA. I went to The Met this summer and saw the show and just recently went back to see the work — it is stunning. I have thought about their space of making, and how they come together and how we use fabric.

I sort of have a similar story where we used fabric all the time, whether it was clothing or whether it was fabric. When I was young, my mother would sew bands of Calico onto my pants because I was growing so tall, so fast, but I was skinny. My mother couldn’t keep me clothed. I was very active too and running around and playing in the mud as all kids should be. I think she sewed these calico strips on the bottom of my pants. Then when my knees would wear out, [she would sew] these patches of hearts or whatever on my knees. We saved fabric. My aunt, of course, the quilt maker, would buy fabric and she had lots and lots of it. There was a fine line between saving and saving too much. I’ve always been aware of this fine line. I want to use everything, and I don’t want to have too much.

I’m a big sharer, I share fabric, and I share things, I think that’s important. If it’s not useful to you anymore, share it. This comes from my indigenous side. The giving of your wealth is really important. It’s never for profit; I’d rather make someone’s day with it. My dear friend says, “You have to give to receive.”

MB | And how does that relate to your Broken Treaty Quilts and the Gee’s Bend quilts?

GA | When I started the Broken Treaty Quilts series, a big part was the fabric and the fabric kit — I call them kits or bundles, they’re 48 to 100 different fabrics. Probably a half or a third of every single kit has used or reclaimed material. Some of it is from my family: my mother and my sister will find things in their closets and say, “Oh, this is cotton, Calico. Gina would like this,” and they send it to me. I have used my former father-in-law’s dress shirts; he passed away in 2013.

What I learned from Gee’s Bend is that the fabric is not perfect, it has stains; there was evidence of a previous life, another youth. That, to me, is important in my growth as an artist. It’s also essential in indigenous communities that everything is used. Everything is used, whether it’s an animal, a hide, the bones, everything is used. So, in an archive, it is a living object because it was once a living object. However, it’s also a living object because every single part of it played a huge role in the survival of a community, and the learning and the passing down of skills. Then with that comes the passing down of oral traditions and history. If we don’t keep it alive, if we don’t keep the tradition of coming together, bringing it back, keeping it healthy, then it will not last, we know that. Each one of us brings different stories in the language together, and we share them so that they continue to thrive.

I was just in Baltimore at a textiles and activism workshop, and I had an incredible experience with a local group of quilt makers. There were many different groups of quilt makers who came together for this social fabric symposium. I met two African-American quilt makers; Glenda Richardson and Rosalind Robinson. They are bringing a community together. They are generating so much love for their community. They create quilts every Wednesday night; they bring the students to work with them, they teach skills of quilting. I brought a broken treaty quilt to share with them and they shared some of their quilts with me. For example, Rosalind shared this quilt with me made from used denim. It was made from her daughter’s clothing from junior high and high school and her grandson and granddaughter’s clothing from the time they were two and four. It included her son’s work pants, dress pants, it was all parts of the denim, from the waistbands, even the snaps were intricately sewn into the quilt. The quilt as a whole just told this incredible story through the used fabrics.

At one point Rosalind held my hands, and we talked about the children, how in the assimilation of Native American children being taken away from their families. She said, “You know, it’s happening at the borders right now. History’s repeating itself.” Quilting is just not about the craft, but histories, about family history, about the importance of community, and it is also political. Engaging at the quilting bee allowed us to talk about activism, and in a highly intelligent manner.

MB | If I could return to the concepts of politics and identity, how do you situate yourself as an artist? Would you consider your work a socially engaged practice? How might your native American ancestry be negotiated in your practice as an artist? I understand the cultural-political quagmire this question contains but I ask in light of a review of your work by critic Lucy Lippard in which she opines, “For those artists who still feel responsible to a near or far traditional community, the goal is to make art that is both satisfying to the individual maker and comprehensible, attractive, or provoking to many in and beyond these communities. It’s not an easy balancing act.” I continue to think of Stuart Hall’s thoughts of the continued negotiation of identity, particularly through colonization.

GA | It is complex. Lucy is speaking probably of a couple of different groups of artists or groups of artists who have an understanding, and they have a knowledge of the community. And no matter what, whatever you see from the outside of a community is always entirely different when you’re inside the community. I think what Lucy wrote was very, very accurate and inviting the viewer/reader in to consider a complexity that is much, much richer than anyone could imagine.

MB| What does the Broken Treaty project mean to you? Any ideas about future projects you are considering?

GA| My next major project is, I want to do this 50 quilt exhibitions, 50 states, 50 treaties, to 50 different communities. Also, I want the collection to travel. This will be a big project and I have been gathering quilts for it. The entire exhibit must remain together as it travels, because I want it to become a conversation about a social movement. I want to have larger conversations about Native American history and culture. I continually state that this work is not just about myself, but rather this work is about creating sincere change and having the treaties be recognized, and understanding that this history has to be taught in a better way.

Gina Adams’ Broken Treaty Quilts are currently on view as part of the exhibition, Monarchs: Brown and Native Contemporary Artists in the Path of the Butterfly, curated by Risa Puleo at Blue Star Contemporary in San Antonio, Texas, through January 6, 2019.

You can see more of Gina’s work at her website: www.ginaadamsartist.com

Myron M. Beasley, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in the areas of Cultural Studies, African American Studies, and Women and Gender studies at Bates College, USA. His ethnographic research includes exploring the intersection of cultural politics and art and social change, as he believes in the power of artists and recognize them as cultural workers. He has conducted fieldwork in Morocco, Brazil, the US and currently in Haiti. The Andy Warhol Foundation, the Whiting Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities and most recently the Reed Foundation (The Ruth Landes Award), have awarded him fellowships and grants for his ethnographic writing about art and cultural engagement. He has also been recognized for his teaching (awarded teaching awards) and work in the area of pedagogy from the International Communication Association, Ohio University, and Brown University. His writing has appeared in many academic journals including The Journal of Poverty (which he served as guest editor for a special issue on the topic of Art and Social Policy), Text and Performance Quarterly, Museum & Social Issues, The Journal of Curatorial Studies, Gastronomica, ELSE and Performance Research. He is also an international curator.