by Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo

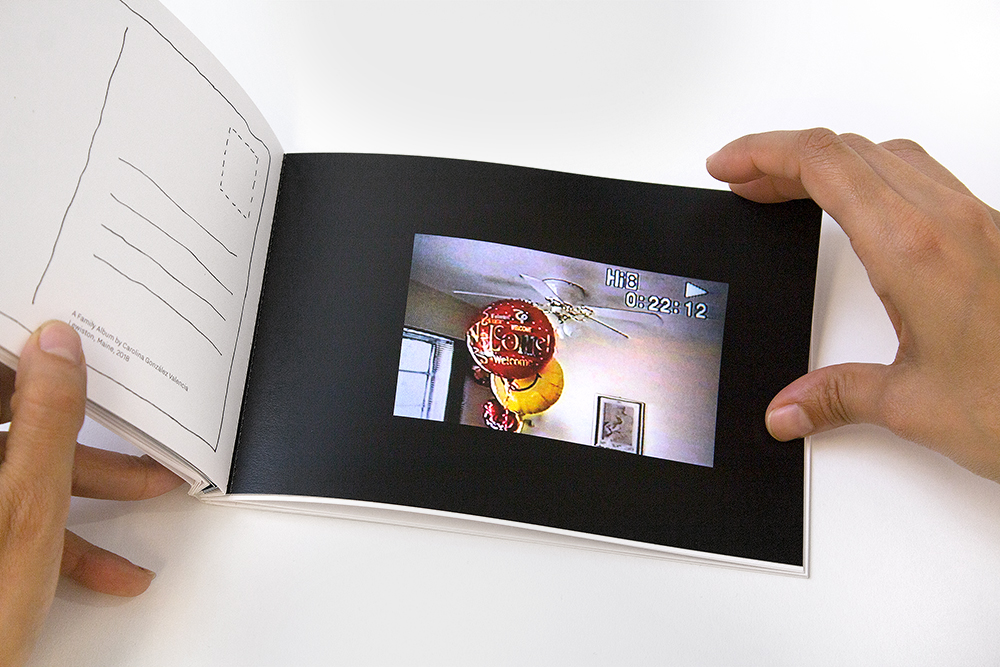

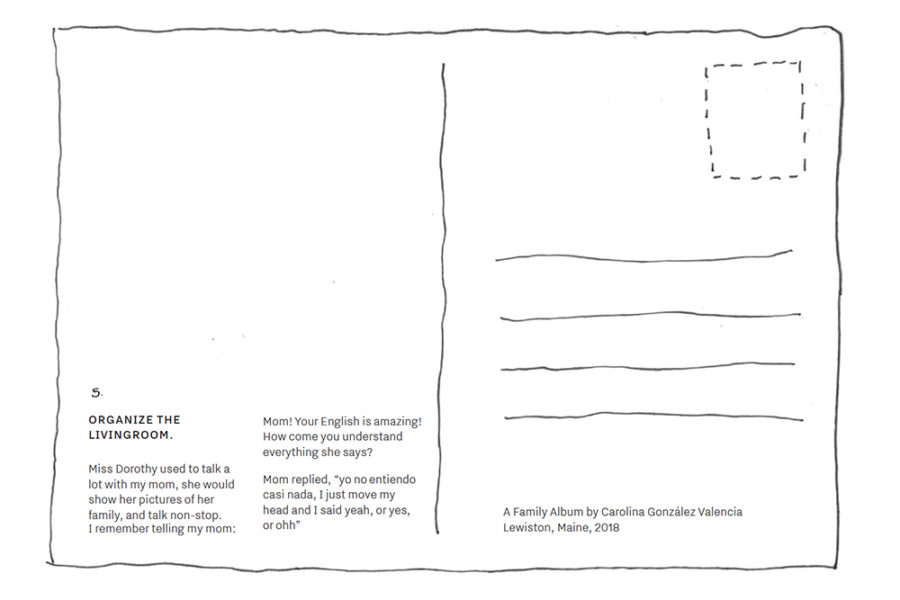

How to Clean a House: A Family Album is a 20-page book of postcards by artist Carolina González Valencia, an interdisciplinary artist working in such media as film, performance, drawing, and sculpture. The book combines instructions on how to clean someone’s house as a domestic worker with milestones from the migration experience of the artist’s family. Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo is a documentary filmmaker, artist, and teacher — she was González Valencia’s professor at the Art Institute of Chicago and since then, a mentor, inspiration, and collaborator. Below, the two speak about Carolina’s new publication, the specificity of their immigration experiences, and the complexities of domestic work in the United States.

Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo | Can you tell me a little bit about how the idea of all these different media came to be a postcards book? I see drawings, I see collage, cutouts, video, paintings, how was the process of deciding the form of a postcard book?

Carolina González Valencia | I had been wanting to make a sort of artist book for a while, so when Orbis Editions approached me with the opportunity to make a publication, I said of course! I knew I wanted to explore the ideas of cleaning a house because I had the text from a performance I did around three years ago and I wanted to give more opportunities for the text to exist.

CCS | Repetition with variation! You go back to something but you go through another door.

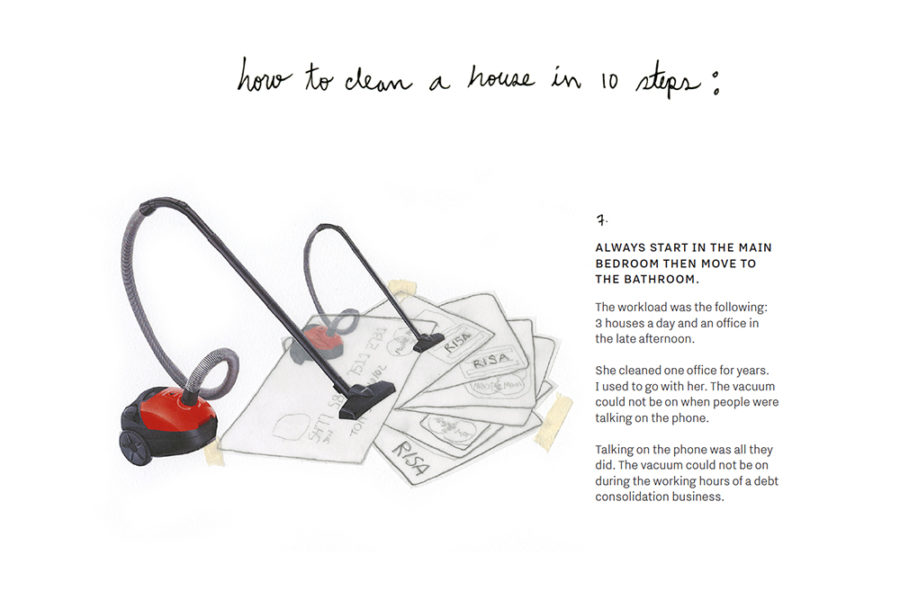

CGV | Yes! In the performance, the engagement with the audience is obviously different than in a film or a book. I thought I could also have some kind of manual that people can keep. When I was writing for the performance I asked my mother to send me the ten most important steps to clean a house — so the work comes from very practical and real steps. But I also wanted to include a different narrative that was not so practical. I’ve been working in the studio using photographs from my family albums, making drawings and paintings out of them. I am very interested how in these photographs of our immigrant narrative were inserted with other family events. For example, a photo of mom eating chicken, or a birthday next to the photo of my mom and brother getting the work authorization card, or the day I arrived in the United States.

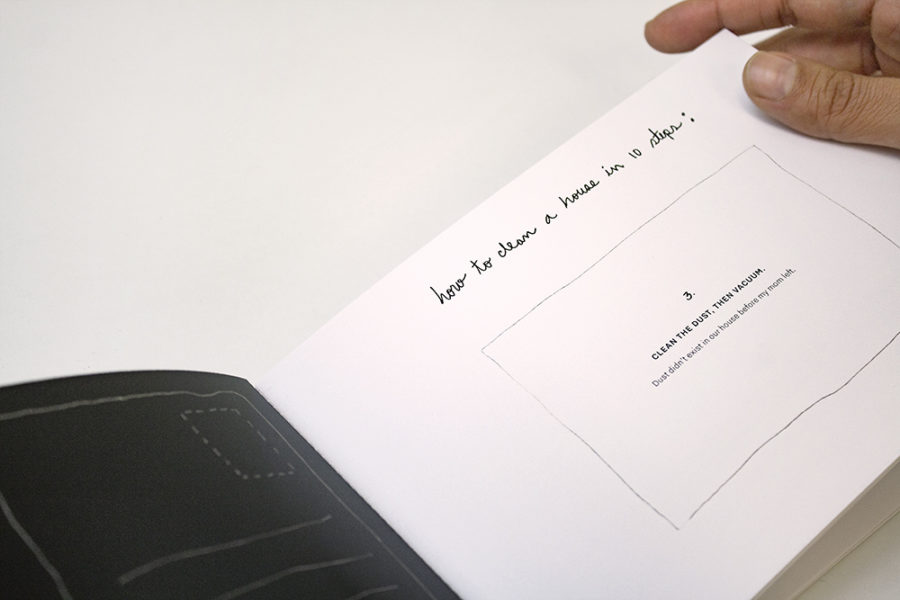

The form of the postcard came to be for many different reasons. I moved to Maine in 2016. I have been observing, learning, reflecting, and questioning my presence here, and the presence of Maine in my life. [It’s] a place that is so different from everything I’d experienced before. From the weather, its culture, to its geography, but also its silence and my solitude. I started thinking about how my mother and I live in these “vacation states”: my mom lives in the Sunshine State of Florida, and I live in Vacationland. Ideals of vacation that we both don’t have access to, though both of us are surrounded by touristic images in postcards of this dream. I thought about creating my/our postcards — I decided I can have the postcards as a family album which also reflects how fragmented and distant my family is. By making it a postcard book, the album could be fragmented and detached, and those fragments could travel. As far as the images and the two narratives in it, in a way, I see them as interrupting or complicating each other. The labor story will interrupt the family story, and vice versa. They are interconnected.

CCS | Yeah! For me, more than interruptions they become a combination of mundane elements — even automatic actions such as cleaning a house following very specific steps in a quite prescriptive fashion — and moments of tenderness, separation, and absence. What I loved about the work and the way it’s displayed, is that each postcard has its space, which is another way of saying that every moment has its place. This has a democratizing effect as there is no attempt at assigning greater importance to one event over another. Whether people are vacuuming, arriving to a new country, or getting a car, the moments are all treated with equal care. This has another effect that I find compelling, which is that the work as a whole lacks sentimentality. The fact that your mom leaves doesn’t get any more screen time than anything else. This is a universe in which elements that are very “small” — and you could even argue “unimportant” — are rescued and reclaimed as if saying, No, this is part of life, too. So, yes, I think they could be read as interruptions, but also as equally important narratives that often are thought of as having different values.

CGV | Exactly, it is kind like a way of reclaiming our personhood in grand narratives where the specificity tends to be ignored, or the complexities tend to be watered down. So many moments exist at the same time and they do not deny each other.

CCS | I also really like the idea that “this is not the story of a woman who discovers penicillin,” but there is value in the domestic work she performs. In this case it’s not only a structuring device, but it represents the very tangible way in which she has framed her life and provided for her kids and herself.

CGV | Yes, and that is part of the complexity of domestic labor. For immigrant domestic workers who travel to another country without speaking the language, leaving their families, this job in many ways liberates them, but also oppresses them in many other ways — those realities exist at the same time. These women are sometimes victimized, but they also provide for their families, become independent, self-sufficient women in the workforce; they contribute to the economy — often in two different countries — just like any other job. I see it in my mom every day: the agency, strength, and how much she learns and is eager to learn, how adaptable she is, and not afraid to keep growing. She shows me the multidimensionality of her job. One of the problems is that domestic work is not seen as a legitimate job, and their employers don’t see themselves as employers. This, among other things, contributes to the oppression of domestic workers and has denied them their basic rights.

CCS | Domestic work is often framed as not worth doing or talking about, like in Chantal Akerman’s film, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, so eloquently shows. Though the film doesn’t tell the whole story, either.

CGV | Yes, it is usually presented flat, not multidimensional. For me it is important to show that this is the story of one immigrant domestic worker in the U.S. — my mom — but this story also comes with all these others stories, complexities, mundane everyday gestures. It’s my way to defend our personhood, especially in representation. I think the exercise of making — and remaking — stories like this one and working with my family archive allows me to see it and understand it better. The stories, the archives, the drawings, postcards, films, speak to this. They work like witnesses.

CCS | When you think about it, cleaning is so much about making something disappear, but the act of putting this project together is the opposite. It is like calling something back into existence, especially after learning in the last postcard that your dad got rid of the photo albums. Cleaning is similar to the act of erasing, but this project has to do with bringing back and even creating images for those events and memories that were not documented.

CGV | Domestic work is all about invisibility. The work is good when you can’t see it. They “erase” what people do not want to see in their homes. On another note, I relate this need to create new documents to the condition of being an immigrant, where in the new place there are no records of you and your past, nothing around you reminds you of who you were. I am creating this new album for us.

CCS | How did you decide which images and media to include in the publication?

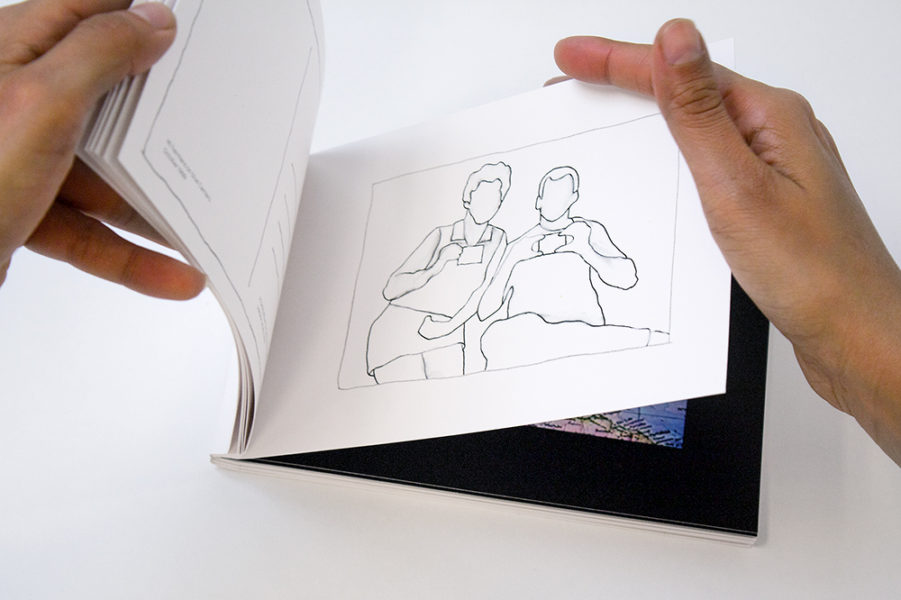

CGV | I think in a cinematic language — for example, in close-ups and long shots. The images from the home movies function like a close-ups: an image of something very specific and very personal. The drawings are more like long shots. They come from photographs, from very specific moments, but through the mediation of drawing I removed a lot of the context. It’s kind like zooming in and zooming out. I was thinking a lot about how to represent absence — by removing, simplifying, and withholding information, by making very simple drawings that look quick — and how those formal aspects communicate more about absence and loss than what is actually going on in the photographs, drawings, or video stills.

CCS | I want to ask about the idea of the ephemeral in the work.

CGV | Like the tape can fall at any moment.

CCS | It makes you wonder if all these drawings are “unfinished”? Are they disappearing? Are they waiting to be more populated? Or, are the people in them leaving, no longer there, or arriving? Concealing and revealing at the same time.

CGV | Exactly, is it a construction? Or a deconstruction?

CCS | It is like when you look at a demolished building, those in between moments.

CGV | That in-between that never stays stable. With the tape, it looks like it was just put there, literally, and that at any moment it could fall. Nothing looks permanent.

CCS | The images also may seem like sketches and putting the tape denies their preciousness, which is another way of keeping away from sentimentality. They look more like attempts while at the same time having the power to conjure.

CGV | I was thinking a lot about that. I wanted the beauty in them to come from those gestures, working together rather than from, let’s say, a beautiful and precious drawing.

CCS | And also what we, as receivers, bring to them. There is so much room for us to complete or add. The fact that they are not finished gives us more room to say something about them or to feel or connect to them in our own ways. So I have to say, I did send a postcard—

CGV | I love that. I love that, first, you insert part of your life in it by writing to someone else who knows what are you talking about. Then on top of that, this object will get modified by traveling — by a stamp, and perhaps get bent, wrinkled, or dirty. Finally, it’s owned by the person who receives it. I love that, that transformation, that I won’t have any control over. It lives in all these unpredictable ways that I will never know.

CCS | It’s interesting that postcards are generally conceived as items related to tourism and travel, even adventure — to all these non-mundane, non-domestic places. So I like that these postcards subvert that function and focus instead on the domestic realm and in an intimate universe.

CGV | I would like to ask you about your work as an artist. Why do we both do it? And why do we go back to these particular themes?

CCS | I guess in my case the easy answer will be to say we are both immigrants, we are both from somewhere else, so we can argue that our identity is marked by that. By virtue of having lived in the United States for a long time, we both have found ways to belong or to somehow fit. I think this idea of belonging, home, or homeland is kind of inseparable from who we are, and that would be the most obvious answer.

Clearly, my work has a lot to do with belonging and displacement, but I think that if I had stayed at home (in Chile) I would still be facing some of the same issues. In other words, being an immigrant, or having left home, doesn’t answer the whole question of why we come back to these issues. Many filmmakers comment on how, in a way, you are always making the same film over and over, and this is because we feel the need to go back to those things that compel us. The need to repeat, to explore, and go back to similar themes can also be understood as a way of going back to unresolved issues. But why these themes? In my case, especially when it comes to the issue of home and belonging, the need to revisit these themes comes from an early childhood memory. I was seven years old when the military coup took place in Chile and that event marked my first experience with loss and with what, up to that point, I understood home as — after that, nothing was ever the same. Every piece I make seems to come from either a sense of loss or from a deep discomfort that I need to explore. In this case, it’s the idea of home and what happens when we lose it.

How is it for you?

CGV | As you said, this obsession comes, in part, from the fact that I am an immigrant, and the more I come to these places the more I find uncertainties or unresolved elements. Making films or publications or performances is my way to deal with the uneasiness. I grew up moving, I have always felt from somewhere else. For example, I always have a hard time answering where in Colombia I am from because I grew up in many different places within Colombia before moving to the United States. Obviously, the time when I moved to the U.S. was the most extreme rupture in my narrative. I can see that probably I respond the way I do because of all the places I have left and arrived. Perhaps I think a lot about home and homeland because I have never felt that I have had one.

I have been thinking a lot about making, and how making became to me a sense of belonging and it became in itself a place, a home. And everything that comes with it: the time I spend making, watching films and looking at art, attending events, the community — it’s like a chosen family and my chosen home.

CCS | That is exactly was I was thinking, too. Work becomes this place of belonging; as far as I am able to make work, I have a place to be from. And you are right, the community that surrounds you and the work becomes not necessarily a replacement, but a sort of alternative family, and a support system.

CGV | Sometimes it is dysfunctional too, like any family! Creating images, this type of language — somehow it is more fulfilling than English or Spanish. It provides something that English and Spanish cannot.

CCS | A language that does not depend on your understanding of words or codes, it is something that transcends all that.

If we go back to this idea of home, and your work being home, you are making work in order to have a dialog with people, with the work, with yourself. I think part of the excitement is working with something that is changing, that is permeable, that is talking back at you. The idea of making work across disciplines doesn’t necessarily submit to a pressure to do what everyone else is doing. It has to do with the idea of valuing fluidity, spontaneity, and the fact that the work is a breathing entity.

CGV | Transformation also happens by and through the act of listening. For me, working in different disciplines is connected with a way to deal with the complexities of identity. I am not only from one place, or I am not only a filmmaker, or an immigrant, or Colombian. I speak Spanish in a different way than I speak English, and they do different things to me, like drawing or having a camera, or teaching. I see interdisciplinary processes as a reflection of who I am as person living in between, or between different cultures, and languages. The fluidity with mediums mirrors that too. I don’t feel whole only talking in one language.

CCS | I like to use language almost as you would use clothing. It is something I can use to cover myself with, to reveal, or to withhold from the audience. I can manage access, I can decide how much or how little I want the audience to understand. With English, it’s also a way of signifying that I am wearing something that doesn’t belong to me, that I can manage reasonably well, but you will still be able to tell that I am borrowing it.

CGV | I like to think about language as a tool to let part of the audience (the ones who do not speak Spanish or English) know that they do not have access to certain things, and that the people who can understand both will have access to more. I find myself lately feeling not so generous, questioning these ideas of “universality” in stories. Right now, I am more interested in letting the audience know that I am not sharing it all, that there are a lot of things that one does not know and doesn’t have access to. I guess I have been fighting with this idea of making stories universal. No! We do not have to understand or have access to everything in order to feel closer, create more empathy, or accept “the other.”

CCS | And stories are not universal, and yes, you are missing things. Sometimes when you think you are understanding everything, you are still missing a lot. And that is who we are. It may be that we have an interlocutor who is not so generous, or it may be that because we have our own shortcomings we can’t always understand things.

CGV | Exactly! That is what I am more interested in, the impossibility of representing the whole picture, or telling the whole story. Language becomes this practical tool to make that visible.

Carolina González Valencia’s book of postcards, How to Clean a House: A Family Album, (2018, Orbis Editions) was created in part with grant support from the Kindling Fund, a grant administered by SPACE Gallery as part of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Regional Regranting Program. How to Clean a House is on sale online at Orbis Editions.

González Valencia is currently exhibiting work from her series Objects to Get Deported at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s 2018 Biennial in Rockland, Maine, through March 3, 2019.

This interview is part of a collaboration between The Chart and Orbis Editions. See the first and second interviews in this series at the links.

Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo is a Chilean-born documentary filmmaker, artist, and teacher based in Northfield, Minnesota. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Communications Studies from The University of Iowa and a Master of Fine Arts in Film, Video, and New Media from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. With ties to both the American Midwest and the central coast of Chile, Cecilia’s work explores notions of displacement and belonging and is rooted in the experience of living in-between cultures. She uses a range of approaches and production methodologies—from the very personal and essayistic to the expansive and collaborative—to create works that move fluidly from the local to the global, and from the intimate to the openly political.

Cecilia is invested in developing effective methods of collaboration with the people who take part in her work by transforming documentary subjects into active participants, co-creators of meaning, and architects of their representation. She is the recipient of an Established Artist Grant from the Southeastern Minnesota Arts Council (2014), a Jerome Foundation Film, Video, and Digital Media Grant (2016), and Artist Initiative Grants from the Minnesota State Arts Board (2016 and 2018). Her work has shown locally and abroad at venues such as MoMA’s Documentary Fortnight, L’Alternativa (Spain), Arsenale (Germany), InVideo (Italy), Melbourne Latin American Film Festival, Puerto Vallarta International Film Festival (Mexico), Festival Internacional de Documentales de Santiago (Chile), Cine las Américas (Texas), National Museum of Women in the Arts, Athens International Film Festival, Tucson Underground Film Festival, Gene Siskel Film Center, Miami International Film Festival, Minneapolis/St. Paul International Film Festival, and Frozen River Film Festival. She teaches in the Cinema and Media Studies Department at Carleton College.