by Veronica A. Perez

In one of the last writings published before his death, Jean Baudrillard writes, “It is when a thing is beginning to disappear that the concept appears.”1 As things fade away, we think that their purpose is gone — that they dissolve into a state of “nothingness”. But this is when the embodiment of the thing appears and wants to be remembered. The thing is discovered in its nothingness: in a place where time and space do not exist. The nothingness becomes trapped in stasis, forever what it once was; it cannot change. This is a pure place, placeless place, only accessible by memory; it’s an intangible thought, which is why it is so hard to grasp, stop and examine.

In Anguish: the Grave Misgivings of Remembrance, curated by Cynthia Nourse Thompson at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at Maine College of Art, this placeless place becomes manifest with meaning. Anguish offers an unapologetic view of mourning, loss, vulnerability, and death through the lenses of fifteen diverse artists. It specifically offers insight into the minute details of remembrance and the process of releasing grief.

In Rosemary Laing’s work, a dozen useless actions for grieving blondes #12 & #5 (2009), a blonde woman is in the midst of her grief — an emotion captured in a split second, made more palpable — and questionable — by a blurred pink background that seems to be commiserating along with her. This placeless place and placeless woman are woven into one. Both reality and fiction intersect in this piece, heightened by the superficiality of the staging, causing the viewer to be shaken by not only its artificiality, but also by its pure, raw, vulnerable emotion. Grief is contextualized and exacerbated. The process of releasing grief is different for everyone and looks different to each of us. Through these two portraits, and throughout the rest of the show, grieving becomes diversified, offering a more fluid understanding of grief. These public acts are heightened through diverse remembrance processes. Real and fake become one, and the viewer is left deciphering the notions of the work for themselves.

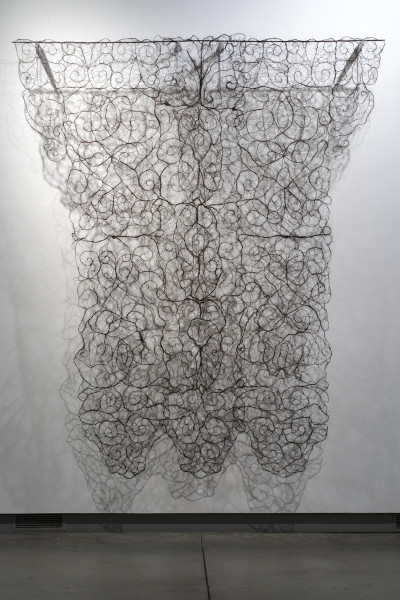

Carson Fox’s Hair Filagree No. 5 (2004) continues this trope of placeless place through her hair sculpture. One cannot underestimate the potency of this piece: strands of hair intertwine to create a delicate lace pattern. Hanging at over nine feet tall, it is hard to deny the beautiful presence of this piece. However, underneath that beauty is a tinge of sadness represented by the materiality of the hair. The idea and the materials come together to create emotion; the Victorian-era practice of memorializing a loved one through a trinket made of hair is monumentalized through Fox’s act of creating this wall hanging.

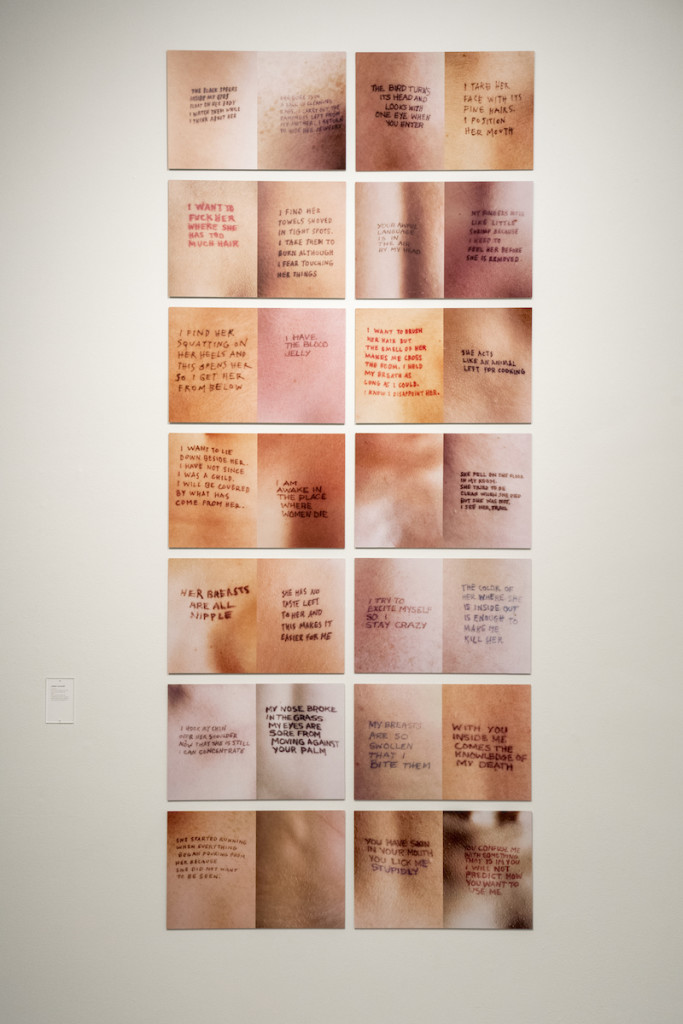

Colombian sculptor Doris Salcedo said, “Death, especially a violent one, leaves reverberations in the air.”2 Jenny Holzer’s piece, Lustmord (1993), embodies this presence of violent reverberations. Lustmord is a German term for sexual murder and torture, often connected with rape. In this work, Holzer has taken testimonies from a victim, perpetrator, and onlooker of sexual torture and has written them into skin to create a jumbled poem of three different perspectives coming together to create a common narrative: remembrance. Notions of violence, loss, and remembrance intersect; we find ourselves at an impasse. This is Holzer’s exploration of the binary nature of words and meaning from an abject perspective: this complex aspect of the piece keeps viewers coming back for more of something they shouldn’t want to experience; it brings us back to something that we need to remember, so that we never let this happen to women again.

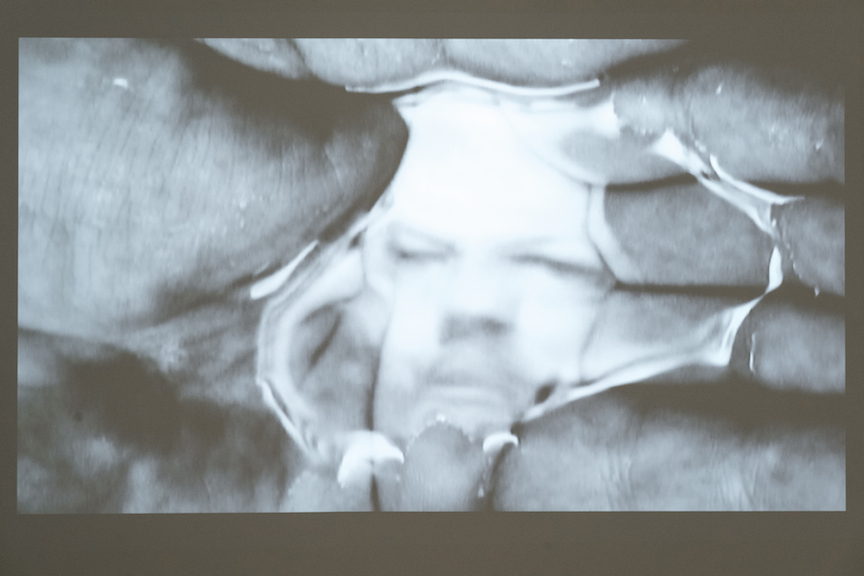

Objects and people will eventually disintegrate, but does that mean that they will no longer exist? Saudade is a Portuguese and Galician term that describes a deep emotional state of nostalgia or profound melancholy and longing for that which was. It is an undeniably potent word, not to be taken lightly. This sentiment is felt in Oscar Muñoz’s work, La Linea del Destino (2006). The two-minute looped video depicts the artist’s attempts to catch his reflection in a pool of water in his own hand. The water slowly drains out as the artist’s reflection shimmers and fades into nothing. Still there, but hard to discern, the reflection continues to stare back at us, beckoning us for remembrance. Muñoz suggests we spend our whole lives figuring out ways that we can live forever; we become so consumed with longevity that we forget to live. La Linea del Destino is dissects mortality, exploring this paradoxical space.

Anguish spans cultures and historical paradigms. Anguish can be either the black veil or the white light; Anguish does not pick and choose its places in time, but comes, sometimes unexpectedly, and eventually. Anguish: the Grave Misgivings of Remembrance generates empathy within the viewer and projects it inward.

Anguish: the Grave Misgivings of Remembrance was curated by Cynthia Nourse Thompson and features the work of Janine Antoni, Louise Bourgeois, Gail Deery, Nils Ericson, Carson Fox, Markus Hansen, Jenny Holzer, Anders Krisar, Rosemary Laing, Roberto Mannino, Martha McDonald, Oscar Muñoz, Piper Shepard, Donna Smith, and Anna Tsantir. Anguish is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art through Jan. 14, 2017.

Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art

522 Congress Street, Portland, ME | 207.699.5025

Open Wednesday–Sunday 11am–5pm, Thursday 11am–7pm. First Fridays 11am–8pm. Free.

Veronica A. Perez was born in 1983 in New Jersey. Perez received her BFA from Moore College of Art and Design in 2014 and her MFA from Maine College of Art in 2016. Currently, she is living, working, and teaching in South Portland, Maine.

Perez works mostly in the mediums of sculpture and photography. Usually utilizing construction and kitschy materials in her pieces, Perez creates intense personal moments by means of hybridization, ideals of beauty, nostalgia, while fragility echoes sentiments of a lost self, and at the same time paralleling contemporary feminist tensions.