by Chris Stiegler

It is rare that I want to see the block, with its carved surface, from which a print is pulled. I tend to think that these parts of the process are best kept to the studio, to the study room, or some other place for amateurs to pore over. Necessarily then, I was surprised to feel a sense of relief that several choice examples of David Driskell’s woodblock carvings were on display accompanying the showcase of a few dozen prints.

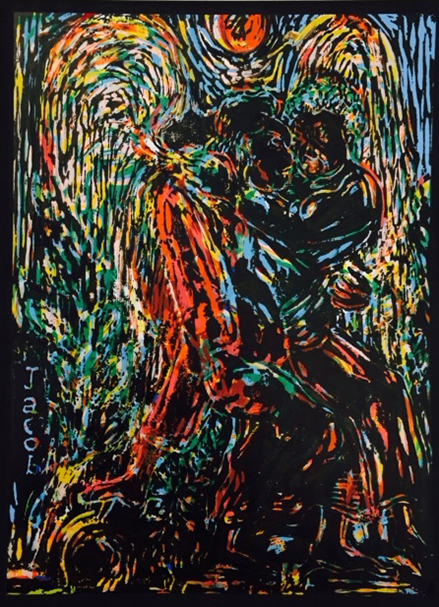

Sweetly these lo-reliefs yield differences in likeness between their marks and the final printed versions, framed and adorning the walls. The prints mute brilliant color behind thin layers of black or creamy grey to finish, echoing a stained-glass window. But these valances leave a sense of longing for the vibrancy of the colors that lay underneath, a sort-of welcomed formal trap. In turn, the narrative hides as well. One print that made me want to see the block was that of an angel wrestling with a man, and the tenderness of a battle scene that shows off an odd anti-macho telling of this well-worn Biblical tale. For Driskell, the Angel and Jacob embrace one another tenderly. The evidence of this is in the block, for the print is not about the story, but instead the icon, legible and quick. Carved with exuberance, the lo-relief tells a story of two figures, negotiating tensions within the frame of a charged conflict. We can all relate; those that conjure frustration and toil are often those we must be the most gentle with.

Other images are rendered with similar formal nuance, making us look at their build to find the nature of their content, in true formalist fashion. Notably three prints titled respectively The Cook I, II, and III show us how Driskell negotiates plane and color. All three present the image of a person heralding within a kitchen. Where The Cook I and II showcase iterations on a theme, The Cook III presents a seemingly more complete rendition by layering these alternative images onto one another. The culmination is not, however, in this third picture, but all three hanging side by side. You see, each print is signed and editioned individually, so we know that they represent collections of images in their own right. Instead, this suite of Cooks is showing us the value of variation and the potential trappings of seeking only a culmination.

Tenderness for subject matter, including that of formal concerns, is part and parcel of this cohort of works. The show, Renewal and Form, presents the confident work of an artist who seems fit to continually re-present this life. Here we see a life is one of lux, calm and voluptuousness, enraptured with color, girded by form and entangled with empathy. Artists like McArthur Binion and Romare Bearden both come to mind here as peers in a kind of fraternity of African American formalists. Like these two men, Driskell’s career is dignified and entrenched in a discipline, and also ever-aware of how differences are to be viewed, interpreted, and elevated. Jacob may always wrestle with his Angel, but sometimes he may also be caught in a caring embrace.

The presentation of these prints and some of their respective woodblocks seemed to forge a bond with work of Sam Cady and Mark Wethli, the two other artists currently on view at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art. Fused by ideas and things — how artists build the world they imagine — these three shows play at process and objecthood. Thankfully they all do it well.

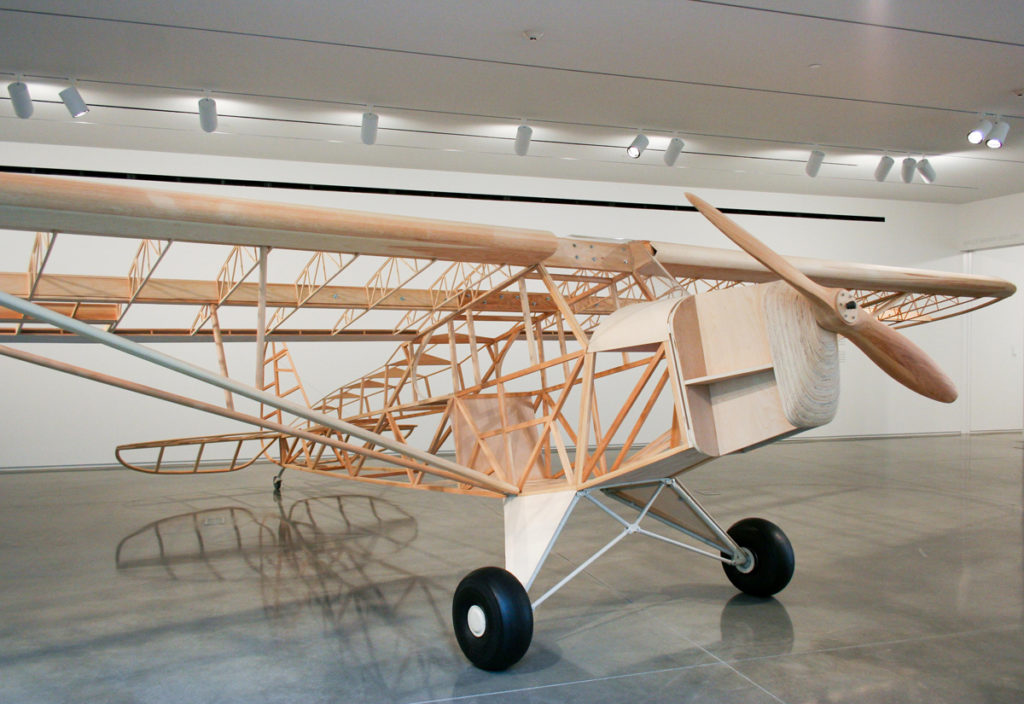

For Mark Wethli’s Piper Cub to be built to wooden armature is to be perhaps the most of the object the thing can be. Every audience member, every viewer thinks about the skinless vessel, its size, its beauty, and its capacity. We all think we see a plane. Before too long we realize that this thing before us won’t fly. Thereby every person is thinking about it as an object. The opposite of that is seeing a plane in full, say at an Air&Space Museum, where we may imagine ourselves in flight within the cockpit, or at the very least imagine the sky around it as it is whisking through the clouds. But this cub is merely a thing, and therefore proudly that thing.

Adorning the walls are monumental drawings of preparations perhaps. There is a certain variety of omniscience in the wooden object that seems to presage the paper works. This funny relationship adds a luster of vanity to the project for it seems that this plane is self-aware. Different than the circuit established by woodblock and print for Driskell, this shift from the third to the second dimension seems stoic. Whereas Driskell tends toward the emotions and tempos of the sensuous, Wethli’s hand evidences slick refrain and time-spent. The two shows play well through the doorway that divides them, passion from pause, or romance into classicism.

Sam Cady toes the line by dancing gingerly between Driskell and Wethli. His show of shaped canvas pictures is a doozy. Rarely can I say I laughed at a show of paintings, but the small sculpturally positioned painting of those two-pronged pillows Cady and I know as husbands (I know, gross) was full of humor and good sense. This little green wonder was a rollercoaster. It sits about shin-high, propped up by a well-rigged apparatus. The rendering is photo-realist and the form is interesting, but that this little friend reminded me of teenaged hang-outs, of funky basements, and of freshman year dorm rooms was enough to make me sit down.

And it was a shaped canvas. Long a favorite of mine, when executed well a shaped canvas can shift the wall. Notably Ellsworth Kelly did this by adding slices of color to institutional and residential walls. But Kelly was serious, a formalist, of the same generation as Driskell. Intermingled with them are folks like Frank Stella and Elizabeth Murray that have moved shaped canvas painting from purely dogmatic to dogmatic and zany and fun. It is not that seriousness or consideration left the studio; in fact it was expanded to include such things as goof, zing, and ha. Sam Cady has been hip to all of this and here presents some really earnest and really funny paintings about quotidian life. What accompanies the paintings here is a sense of being about and of a life of noticing things. The pattern carved by the shadow under a highway overpass creates, like Kelly, a slice of action in a mutable gallery wall. The isolation is chillingly analytic but also comforting, as the presentation of a shadow seems to rake a warm summer breeze across the back of your neck. Where we were with Driskell in his printing process, and with Wethli in his analyses, here we stand with Cady, in the world and looking. The maker is here with us, again.

Mark Wethli’s Piper Cub is on view through May 14; David Driskell’s Renewal and Form is on view through June 4; and Sam Cady’s Parts of the Whole is on view through June 11.

Center for Maine Contemporary Art

21 Winter Street, Rockland, Maine | 207.701.5005

Open Wednesday–Saturday 10am–5pm and Sunday 1–5pm. $6 general admission, free for members and children 12 and under.

Chris Stiegler is a professor and curator of contemporary art based in Portland, Maine. Currently he runs the Institute for American Art with John Sundling, his husband and collaborator. The project, situated in their apartment, showcases the work of a single artist per show as a way to engage the viewer differently. Founded in 2012, the Institute has shown the work of artists, curators, cultural producers, and publishers. In the coming years we hope to expand our geographic reach while maintaining our domestic operation.