by Jenna Crowder

It is possible to redefine a legacy. Correctives that serve to deepen our collective understanding of art offer exciting historical and cultural ramifications for curation and scholarship. New dialogue can shape how we exert and experience influence in an art world defined by both.

Marsden Hartley’s Maine, a collaboration between the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, is an exhibition that offers a specific perspective on what this kind of scholarship can look like. Curated by Randall R. Griffey of the Metropolitan, Donna M. Cassidy of the University of Southern Maine, and Elizabeth Finch of the Colby Museum, this exhibition, named the “first large monographic Marsden Hartley exhibition to appear in a New York museum since 1980, when the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted its seminal retrospective”, is currently on view at the Colby College Museum of Art through November 12.

I spoke with Beth Finch on a recent August morning at Hewnoaks Artist Colony in Lovell, Maine. She had suggested meeting at Hewnoaks to purposefully imbue our conversation with the importance of place to Hartley and his work. Hartley spent significant time in Lovell and at Hewnoaks in particular, taking in views of Kezar Lake and the White Mountains across the lake to the west, and using these memories to paint elsewhere. I came to find that Finch shares my opinion that Maine is not — and has never been — an isolated place, that the lush landscapes and rich cultures here naturally act as conduits between places, perhaps especially between urban and rural sites. Maine, for Hartley, was as much a hold against the mass art market as it can be now for contemporary artists, its position geographically and culturally equipped to provoke necessary alternatives to the mainstream.

Marsden’s Hartley’s Maine reframes the conversation on his work to include many of Hartley’s early Maine paintings. In her catalogue essay, “Becoming ‘An American Individualist’: The Early Work of Marsden Hartley,” Finch renegotiates Hartley’s oeuvre to provide a more nuanced view of his intentions, relationships, and work. I spoke with her at length about the challenges of recontextualizing current understandings of Hartley’s life and legacy within the specificity of Maine while simultaneously celebrating his influence on a broader art world and global movements.

Jenna Crowder: Why do you think Marsden Hartley’s earlier works are less frequently examined than say, his later figurative or landscape works? You’ve called these early works radical, rejecting the idea that they’re derivative — can you tell me more about how we can read them this way?

Beth Finch: The early Maine works — the paintings Hartley made during roughly the decade that he spent in this area, in the Lovell region and in Stoneham — have been overshadowed by the German works.1

In the second half of the twentieth century Hartley’s early German paintings became so important that it was easy to dismiss the earlier works as derivative and perhaps not see a connection between Post-Impressionism and the kind of abstraction that was emerging in Europe in the early twentieth century. Some of the works in the Colby/Met exhibition are quite abstract and use the approach to series, repeating the same compositional gesture over and over as an avenue to abstraction. They maintain absolutely a connection to representation — to landscape particularly — but I think they’re more connected to the German works than they’ve been given credit, and perhaps they were sort of convenient to overlook.

What I find really fascinating is that Hartley met [Alfred] Stieglitz in the Spring of 1909 and what Stieglitz saw were artworks rooted in place: that was something he wanted to bring to the attention of New Yorkers, to the world that was interested in the emergence of Modernism in an American context. That tells a slightly different story, one that connects Stieglitz to Post-Impressionism in a way that hasn’t been fully appreciated yet. So that interests me.

And then I think the claim that Hartley was derivative at the outset of career has been overstated and has kind of become “stuck” to him as an idea. Hartley was an artist who purposefully made connections to other artists.2 Many artists do this — we all do — connect ourselves to other artists or people who we feel are kindred spirits. Very early on in Harley’s career, for instance, the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson were so important to him — the Transcendentalists in general. He was late to that banquet, too, but they were so important to his connection to the landscape and the way he painted. And Walt Whitman was equally significant to him — in fact the earliest surviving artwork by Hartley is a painting of the front of Whitman’s rowhouse in Camden, New Jersey. Camden, New Jersey, like Lewiston [Hartley’s birthplace], was an industrial part of the world. Hartley had an aptitude for thinking about how his own biography and his own aspirations reflected and refracted those of other people he admired.

With someone like Giovanni Segantini — Hartley came across this magazine, it was a German magazine that contained color reproductions of paintings by Giovanni Segantini, who was an Italian Neo-Impressionist, with a real painting system, alliteratively called the “Segantini stitch”. Segantini was painting mountains, and there are also some other fascinating parallels between those two: like Hartley, Segantini lost his mother at a very early age, he was also born into a working class family — I don’t know how much of this Hartley knew because that magazine was in German, but it does contain Segantini’s life story. If he was able to learn anything about it, he would have noticed those parallels. Segantini died in 1899, so was totally out of the picture. He could, in a sense, be freely invoked and absorbed by Hartley. And Hartley was an autodidact; from a very early age, he was teaching himself. He took those old-style color reproductions that don’t register quite right, and he saw the subject matter — mountains; in this case the Italian Alps — and it was one of those light bulbs for him. He started doing his rendition of the Segantini stitch using this area, Kezar Lake, the mountains looking toward the White Mountains, Speckled Mountain, some of the other mountains you see around here, to, in a sense, adopt his own Maine. And it was absolutely a chosen Maine. It was not the Maine he was born into, which was much more industrial.

JC: I’m interested in the “two Maines” of Hartley’s life — the industrial cityscape of Lewiston/Auburn in which Hartley grew up and the claimed heritage of the rural landscape — understanding that he was part of these urban hubs and chose to be here in Maine and talk about the rural. In particular, he spent a significant time at Hewnoaks, embracing, at least philosophically, folk traditions and craft practices. What do you sense he found in the rural that he couldn’t — or avoided — in the city?

BF: He was, as you point out, absolutely a cosmopolitan. He was born in Lewiston, moved as teenager to Cleveland — a very industrial part of the world, the center of the iron industry and where the steel industry was just emerging. He was in Cleveland for a few years, and, when he was able to secure a stipend, moved to study in New York City, choosing an even more urban context. By the time he began to come to this area — his first summer was in 1902 — he was in Center Lovell. Donna, Randy, and I talk about Hartley’s “anti-Modern Modernism”, in a sense, the flipside, the alternative to painters and artists who were interested in representing the city. Hartley was never interested in representing the city; in general, he was more interested in folk culture.

In the broad scope of that, starting in the late nineteenth century, there was an increasing interest in craft, in large part in reaction to industrialism. Hewnoaks is the product of that kind of thinking; the Volks were city folk, too, who came here in the summer. Hartley knew Marion Volk. He said, in his autobiography, that he “didn’t even get close to Douglas Volk”, that’s how he puts it. He came to Lovell for the mountain views but he mentions Douglas Volk in a letter to a friend when he was thinking about the area. It was logical that he would want to connect with Volk, who was a much more prominent painter at that moment.3 Apparently, Hartley stayed at a place near here but never on this property specifically. But he would have been in the midst of the Arts and Crafts movement. And in his letters he talks about the connection between textiles and painting and nature, making those connections.

As I was doing research on this area and on Hartley, it helped me understand one of the points of focus or interest that patterned how he responded to the idea of the stitch. Partly it was Segantini, but partly it was how quickly the stitch became a means of expression. And it quickly loosened. One of my most favorite works comes to us from the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis, Landscape No. 36, a bright red landscape. It’s autumnal, the color is really keyed up, the trees flank the mountain, but it’s as if they’re engulfing it in flames. When we’ve talked about the radical nature of the works, it’s those kind of works that we’re thinking about. There’s a painting on loan to us from the Philadelphia Museum, called Winter Chaos, Blizzard, and a work from the National Gallery, that is also a scene that is really moving toward abstraction.

JC: Hearing you talk about the energy, an almost violence of the landscape and how he’s painting them — the flame of trees engulfing the mountains — feels very different from how we talk about landscape often, particularly with Impressionists. When I think of landscape in general, especially in Maine, there’s a tendency to think of it as an escape, of serenity, which is actually not at all how you’re talking about these. It’s exciting to hear you talk about them in this way.

BF: Those early works, from that 1907–1908, some into 1909, those can be just absolutely vibrant and almost euphoric — there’s a sense of that in paintings like Hall of the Mountain King. And then you get to the other side, starting in 1909, when he created his Dark Landscapes series, also using this Lovell region — or his memory of it at that point — as a source. The contrast, the dichotomy between darkness and light, is remarkable in Hartley’s early works. That he could take the same subject and see it entirely differently. In the landscape from the Weisman Art Museum there’s a suggestion of a home or a farm at the base of the mountain. In fact, Colby owns a landscape called Desertion, it’s not a place that’s inhabited or the suggestion of a home, it’s really the opposite, a destitute place. Hartley would have seen deserted farms in this area; there was a consolidation of farms happening in the early twentieth century. Fewer farms in fewer hands.

JC: So do you think that that switch was largely predicated on historic fact or was there also some sort of—

BF: Emotion?

JC: Yes, in his life at that time?

BF: I think it was both. I think part of the reason that [the work] was and is still so evocative is that is connected to actual social trends in the early twentieth century. Hartley, in 1909, stayed in New York City: he did not come to the area and he painted in a small room. He painted these very somber landscapes. He had come across, very importantly, at that time, the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder.4 Hartley saw a painting that’s now in the collection of The Met that’s called Moonlight Marine and, soon after, he visited Ryder’s studio. The painting Hartley saw is very beautiful. It shows the silhouette of two boats on a storm-tossed sea with moonlit skies. Hartley wasn’t ready to start painting coastal scenes, it would appear, in 1909–1910, but he basically took that idea and saw it in terms of an inland scene he knew very well. So the little boats, in a sense, became these deserted homes or farms, and the same kind of moonlit skies, which he had seen here, right? Those two poles, I think, the dichotomy between the very bright colored, exuberant, sometimes violent — as you note, the violence of weather — very early on in his career in that first group of surviving works, and then in 1909–1910, the Dark Landscapes.

JC: Region was something I wanted to ask about. The term “regional” has certain positional connotations these days — sometimes pejorative, sometimes becoming synonymous with provincialism — and fairly separate from the movement of Regionalism. (In the catalog, Griffey notes that Hartley was critical of other Regionalist painters like Benton and Wood, but also sympathetic.) How has looking at these ideas through Hartley’s work enabled you as a curator to tease out these issues? To shape ideas on being from a place — or rooting yourself in place — that can maybe overcome some of those more pejorative connotations?

BF: Yes…I don’t know that I’ve entirely figured this out! We often think of Maine as an isolated place, as a provincial place — but in fact, it was not then and it still is not now. Hartley’s Maine was a place where he tried out ideas he was hearing about elsewhere. It was a conduit, in a way, between places. How [do] we go about both connecting with [place], the usefulness of origin, and then the potential pitfalls of the myths that grew up around it? [We have] ideas, for instance, of New England being the birthplace of America and along with that comes the potentially problematic focus on ideas of purity and authenticity and honesty. I think there’s a lot to unpack there and the more we approach it with a critical mindset and an inquisitive outlook, the better.5

When we were developing this project, I was uncertain how Hartley’s Maine would play in New York City. Maybe I shouldn’t have been. It turned out there was a fascination with not only Hartley, but also with Maine. Maybe it’s playing along the lines of the same anti-Modern Modernism. Maybe there’s also the city versus what Hartley represented, which is much more rural; the connection between Maine and New York is absolutely true, and I’m sure as well between Maine and Boston. Interestingly, a lot of the paintings that are being shown at Colby were never shown in Maine. They were made here and left and were shown in much more urban contexts. We have lenders from across the US and one from abroad, so it’s neat to have them here for a time.

One of the things we wanted to do in the show was to say this is one guise among others, this connection to place, where Hartley had, to a certain degree, a love/hate — or at least an ambivalent relationship — to home, as many people do. It’s why home is often such a rich topic for artists. We wanted to draw out the actual complexity of his relationship to home and origin, as opposed to just the prodigal narrative that he played up at the end of his life. In the 1930s, during the height of Regionalism, that played well. The story was about returning home and representing rootedness in one region.

JC: You and the other curators have pointed out the audacity of omitting some of Hartley’s most famous work in this exhibition in order to focus on other periods of his work and “right the history” that we’ve understood up till now. How has curating this show and writing the catalog shaped your ideas of how we process or consume history? Do you see this as a definitive show?

BF: We’re happy that aspects of the work, when brought together in this way, offer a corrective of sorts. Of course the German works are incredibly important, but [this exhibition] rebalances things. I can’t speak for Donna and Randy, but one of the great pleasures of this project has been the extended conversation we three have had, and also being in dialogue with all this other scholarship over time, really, going back to Elizabeth McCausland. She died before completing Hartley’s catalogue raisonné, but she did extraordinary work that is still a resource. Here in Maine, we have Gail Scott, who’s been so important, particularly to Hartley’s poetry and, in general, has done so much research over the years.

There was the retrospective that Barbara Haskell organized at the Whitney in 1980, remarkably enough, because our show ended up being at the Met Breuer — the old Whitney building — and then the show Betsy Kornhauser and others did at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, in 2003, again a retrospective. There had been other exhibitions that looked specifically at Hartley’s Bavarian works and his early German works, Hartley’s work in the Southwest — there’s been a lot of regional focus on Hartley! But we felt like the one region that was really needed, and that sort of set the pattern for the others, hadn’t yet been fully explored.

That’s where we felt we could make a contribution. Scholarship will continue to evolve and I think there are aspects of our project that will move that forward. There is so much more to understand. Going back to one of your earlier questions, around the 20s and 30s and even earlier, in the teens, [there was a] fascination, a push, to find rootedness, and a “native” source for modern art at the same time that other things were happening nationally: some of most draconian efforts to limit immigration, for example; and additional national parks were being established, including Acadia. The convergence of social forces both wondrous and problematic coming from the sense that things–nature, jobs, ways of life–had been lost or would potentially disappear. I think we could all stand to gain from a better and deeper and more nuanced understanding that period.

JC: Springboarding from that, I always ask why we are talking about a specific artist and why now, or again? How do you think his work allows us to think about ourselves and our contemporaneous time? What lessons does Hartley as an artist have for us, and what can your curatorial process, or the show offer?

BF: Next week, one of my colleagues and I are going to teach a class as part of the Colby College orientation for first year students that will take a deep dive into the Hartley exhibition. I’m excited about that conversation. We will talk about origins and the way places get known for certain things over time because of history and because of habit. The ways we know a region, or assume we know it. So we’re going to explore the Hartley exhibition with that purpose. I hope we’ll arrive at new understandings by having the show in the region where the works were made and in the context of a liberal arts college.

For this conversation with you I wanted to be around Hewnoaks because, although Hartley didn’t live on the property, it was the largest and best known example in this area of an arts and crafts revival, a place created by people fascinated with the past. You know, when I was delving into the Lewiston Sun Journal, even at that moment and in that context, there was the impulse to escape from Modernism and industrialism. Lewiston is — I don’t know what the travel time was at the turn of the century, but — now an hour away, and driving over from Waterville this morning, it is seemingly a world away. Those myths and qualities of place are still so strongly evoked in a place like this.

Marsden Hartley’s Maine is on view at Colby College Museum of Art through November 12, 2017. It was exhibited at the Met Breuer in New York City from March 15 through June 18, 2017. The exhibition includes approximately 90 paintings and drawings.

Colby College Museum of Art

5600 Mayflower Hill, Waterville, Maine | 207.859.5600

Open Tuesday–Saturday 10am–5pm and Sunday 12–5pm. Open on Thursdays until 9 pm during the academic year.

- Elizabeth Finch: “Hartley went to Europe for the first time in 1912 and made his way from France to Germany. I think Germany reminded him of Maine, particularly the area of Bavaria, and he felt a close connection to the German people — a sort of fascination with Northern people in general. The artworks that he made during that period — when he was looking at Modernism and artists like Gabriele Münter; that absorption of that avant-garde moment in a very quick fashion — those were the artworks that were of the greatest interest to art historians who considered Hartley in the late twentieth century. He died in 1943, and in the post-WWII era, we know, of course, that Abstract Expressionism emerged. Hartley was really considered a precursor to American abstraction, and in that regard, those works were embraced wholly by art historians and others. If we look at a textbook or a book on Modernism in general, Hartley is considered this very important figure — and he was and is — but the interest has been weighted toward a small subset of paintings. There was a great exhibition celebrating the German works that was at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, that started in Berlin. Hartley would have been surprised that those works would have become how he’s now best known. Because of their association with Germany, those artworks were problematic when he showed them during his lifetime, so when Hartley died, what he was best known for at the time was the last chapter of his career, which began in 1937. He had returned to Maine that year and that period ended with his death in 1943. When he died there were several obituaries in national news, including Time and Life magazines, and in both of those outlets, he’s represented as a painter with regional ties, specifically to Maine. I think the Time coverage, the headline is “Maine Man”, and in Life, it’s something to the effect of “Fame Catches Up to the Painter-Poet of Maine.” Hartley died thinking that the artworks that would be his greatest legacy were those from the last chapter of his life.” ↩

- “Influence is a curse of art criticism primarily because of its wrong-headed grammatical prejudice about who is the agent and who is the patient: it seems to reverse the active/passive relation which the historical actor experiences and the inferential beholder will wish to take into account. If one says that X influenced Y it does seem that one is saying that X did something to Y rather than that Y did something to X. But in the consideration of good pictures and painters the second is always the more lively reality. …If we think of Y rather than X as the agent, the vocabulary is much richer and more attractively diversified: draw on, resort to, avail oneself of, appropriate from, have recourse to, adapt, misunderstand, refer to, pick up, take on, engage with, react to, quote, differentiate oneself from, assimilate oneself to, assimilate, align oneself with, copy, address, paraphrase, absorb, make a variation on, revive, continue, remodel, ape, emulate, travesty, parody, extract from, distort, attend to, resist, simplify, reconstitute, elaborate on, develop, face up to, master, subvert, perpetuate, reduce, promote, respond to, transform, tackle…—everyone will be able to think of others. Most of these relations just cannot be stated the other way round — in terms of X acting on Y rather that Y acting on X. To think in terms of influence blunts thought by impoverishing the means of differentiation.” —Baxandall, Michael. Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1985. p.58-59. ↩

- Finch: “I think in the end, Hartley had a stronger connection with Marion, at least to judge by his autobiography, which we have to take with a grain of salt. It was written almost thirty years later and when he was shaping his legacy. My hunch is that Douglas didn’t give him much time or attention, this young painter who was hanging about.” ↩

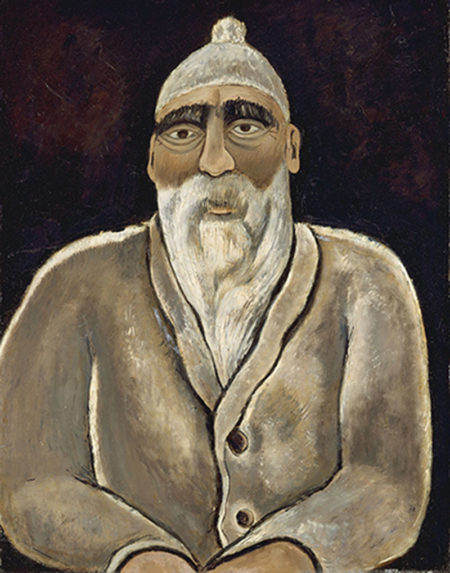

- Finch: “Many years later, Hartley portrayed Albert Pinkham Ryder in a portrait after Hartley returned to Maine; I think the date is 1938. He did a series of paintings, among them Abraham Lincoln, John Donne…a sort of miscellany of all of his heroes. Ryder was among them. That painting was itself based on a memory that Hartley had of passing Ryder on the street in New York City one night. They happened to live in the same neighborhood, and they had met each other, but they remained little more than acquaintances despite Hartley’s reverence for Ryder. ↩

- Finch: “We even have it here, with Marion Volk. She had a deep commitment to authenticity and rootedness, beginning with the sheep that were raised for the wool that was spun that became the rugs that she and the women in the region wove very laboriously, hand-dyed and so forth — a commitment to process that was absolutely extraordinary. And in fact, so difficult that the actual industry couldn’t fly because they couldn’t make enough of them! It was a stance against the mass market and toward the value of things that are handmade. In the midst of that, the things that they were weaving had these Native American designs that came from, probably, Plains Indians — it was really out of place and without, I think, any real understanding of what that kind of appropriative gesture meant. And they weren’t alone. There was a fashion for this kind of imagery and they picked it right up.” ↩

Jenna Crowder, Co-Founding Editor at The Chart, is an artist, writer, and editor. Her writing has been published in The Brooklyn Rail, Art Papers, BURNAWAY, Temporary Art Review, The Rib, Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, and VICE Creators Project, among other places.