by Jacquelyn Gleisner

Behind the counter at my local pet store, inside a large, brown cardboard box, dozens of tiny crickets jumped inside their clear plastic bags. Their flutterings charged the box with a frenzied energy. “I’ll be back soon,” a man said as he exited the store into the bright summer sun. Turning to the next customer, the cashier explained that this man had just purchased all of the store’s crickets — I’m guessing over a hundred of them. The sole (and highly eccentric) birthday wish of his wife was to release these insects into the wild. Together this couple would watch the crickets bound for freedom, hurling their bodies in all directions near the bank of a local stream.

As I waited in line imagining this scene, so artfully conceived and planned, its zaniness began to recall a 1960s Happening. Happenings — the name’s implied caprice contrasting with the strict orchestration of these events — involved similarly erratic actions such as a nine-foot-tall costumed foot dancing with a torso on a stage. Or in upstate New York, a group of people licked strawberry jam off the hood of a car in Allan Kaprow’s Household (1964).1

Kaprow was an artist, intellectual, and the acknowledged leader of the 1960s Happenings scene. Drawing from the Nouveau Realists in France and John Cage’s avant-garde performances at Black Mountain College, Kaprow believed that “the line between the Happening and daily life should be kept as fluid and perhaps indistinct as possible”2 — and this blurry categorization allowed these bizarre scenes to fade in and out of fashion within a decade or so of their inception. Happenings stopped happening, but they left an indelible mark on the performative arts that followed.

Several weeks later, a vision of this strange insect emancipation surfaced inside the studio of John Coleman on the industrial edge of the West End of Portland, Maine. Alongside 14 other artists, I watched as Coleman shot at a bundle of white jugs tied together and suspended from the tall ceiling of the warehouse. A milky liquid dripped onto a rough halo of barbed wire and then landed on a large, circular rubber floor mat. Coleman read a poem he had written as the viscous fluid oozed from the wounds.

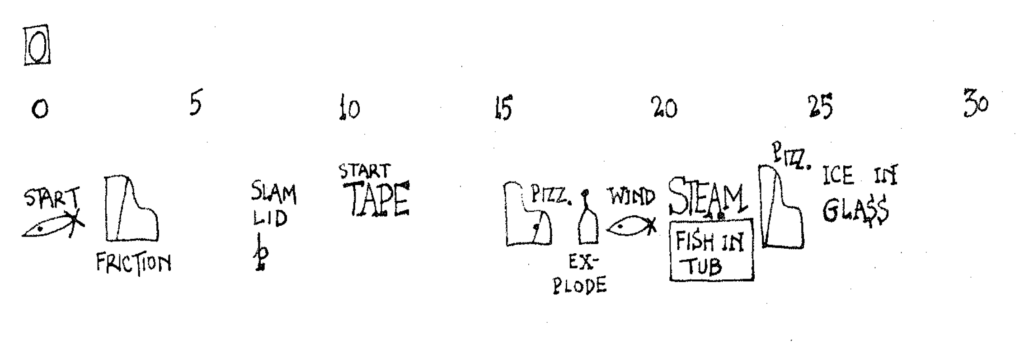

This performance concluded an afternoon of “Curings” — the name Coleman has given to these gatherings. To date, there have been four of these events, each following similar parameters. Each participant designs a 15-minute experience for the group as a way to cultivate experimentation in an artist’s practice. This concept came to Coleman while he was reading a biography of John Cage, the composer and artist whose college classes at the New School in New York City had no set curriculum. Cage invited his students to use their time together in whatever manner they needed and Coleman’s Curings have adopted this structure.

Meanwhile, waves of nausea passed through me. Two weeks before arriving in Maine for my weeklong tenure as The Chart’s 2019 Visiting Critic, a second pink line appeared on a chalk-white strip tinged with fresh urine. After four hours of performance, exhaustion was beginning to overtake my newly pregnant body, tender and bloated as a piece of stale bread soaked overnight. The pierce of gunshots snapped me back to consciousness and my mind recalled those lucky bugs. Spared a grim fate, the crickets formed an unlikely parallel to Coleman’s performance — twin gestures of release and relief.

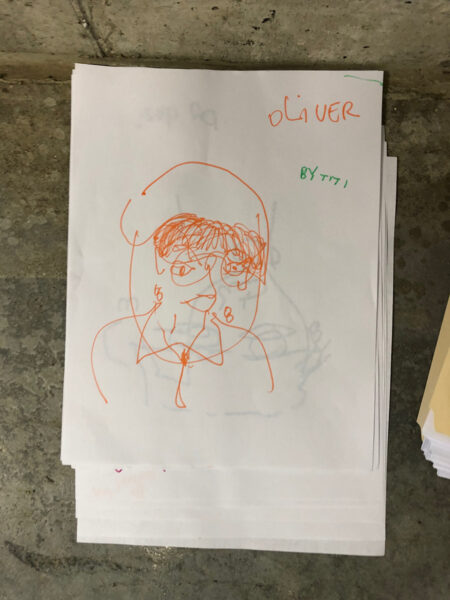

During my seminal Curing experience, collective napping as a form of capitalist resistance, bespoke blazers pieced from newspapers, and acoustic renditions of Beyoncé songs were some of the avenues explored. We sat on the floor scribbling blind contour drawings of one another using a rainbow of markers at my request. We listened to an unconventional love story, accompanied by a humorous PowerPoint presentation. Finally, we attempted to complete a lengthy IRS document on behalf of an individual born in Hong Kong, yet designated a Chinese citizen according to the Nationality Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Before we embarked on the afternoon’s programming, Coleman advised the group to practice self-care, making note of the bathroom’s location and the cooler of drinks. He also urged us to focus. Each person was prompted to train their eyes and energy on the others in the room as fully as possible, encouraging “noble attention,” as Coleman described it.

Tired, irritable, and distracted, I struggled to stay present that afternoon and for many months to come. For all of the first and most of the second trimester, my mind — more than my body — seemed saddled with my lumbering ideas of the pregnancy. I had never been pregnant before, but I have been around pregnant women my whole life. A sudden realization — beyond obvious but novel to me — was how so many of these dazzling women had moved through their pregnancies unperturbed while I vacillated between feelings of anxiety and confusion.

When the white outline of a skull appeared inside the inky cavern of my uterus on a screen during the first ultrasound, I struggled to accept what I was seeing as fact. Screens distract us, imposing distance from our thoughts and each other, I thought. As an artist and critic, I’m trained to decode images, to pull abstruse meanings from the murk, but I could not connect the image on this screen with my body. I knew my body was pregnant, but my thinking brain did not acknowledge this new reality.

This failure to compute came, in part, from the imposed ignorance of many within my direct orbit. Like many women, I felt reluctant to share the news with people outside of my innermost circle for personal and professional reasons. On more than one occasion, I’ve been warned of the difficulties of navigating the contrasting paths of an artist and a mother. Similar barriers persist in higher education. Anecdotally, many women have shared with me they delayed their entry into motherhood until they had secured tenure.

On the exterior, I looked (mostly) the same for many months, yet internally and emotionally, the shift was severe. Almost immediately, I felt reborn, the old version of myself vanished. The new me got teary-eyed during cloying advertisements on social media. The new me tired easily and shifted into a less productive being. The proud, efficient multi-tasker I had been morphed into a slow-moving, nap-loving softy. The prideful idea of my identity I had been nurturing — a strong and self-sufficient woman — seemed forever asleep. I was all squishy feeling, no stiff facts.

Online and in print, gestational advice abounded. Tragic stories — lost pregnancies, freak anomalies, rare genetic diseases — were never farther than a few keystrokes, but why weren’t more women writing about the intricate emotional life of their pregnancies? Recommended books were uniformly prescriptive. Short of paying a therapist to unpack my wavering thoughts, safe spaces for transparency and honesty were rare.

When I did begin “showing” — and subsequently sharing the news of the pregnancy more broadly — I collided with a wall of expectations. Wading into the convoluted currents of pregnancy — its opposing streams of physical and emotional labor — I felt compelled to package myself as joyful, like the most decadently wrapped present.

And I did experience joy, but it was one of many contemporaneous sentiments. Still, sharing a more dimensional account had the capacity to injure anyone unable to conceive or carry a baby to term, I worried. Culturally, women seem trained to endure this feat, despite the fears often hurled at them from the medical community and elsewhere. We are instructed to be resilient, yet stereotypes tell us we are weak and needy at the same time.

As the Curing churned in my recent memory, I turned to performance art as a proxy, a potential metaphor for these extended tests of my strength. Being “in the family way” — one of the numerous euphemisms that point to the inadequacies and embedded sexism of language related to this experience and others unique to women — comes with a scripted set of actions: prenatal vitamins, alcohol abstention, limited caffeine, and much more. Each day, I enacted a personal set of Curings, every improvised act flowing into the next unknowable trial. Inside darkened rooms, I was probed during bi-weekly transvaginal ultrasounds that checked the length of my cervix (a precautionary measure recommended by a team of doctors). Strangers and acquaintances alike massaged my belly, with or without my permission. I researched daycare facilities for a baby I had not met and tried to accommodate a potential breastfeeding schedule into my fall course load. With the tirade of interventions and unsolicited touching, I perceived myself as a character inside the performance of pregnancy.

Expecting is exactly that. For nine or so months, a woman’s being swells with anticipation and agitation as the world moves around her and another life forms inside her. She understands the duration of her quest and she feels the movements of the forces within her body. The crisp, assured shape of knowledge engenders a fuzzy silhouette through lived experiences. Uncertainty becomes more familiar than not.

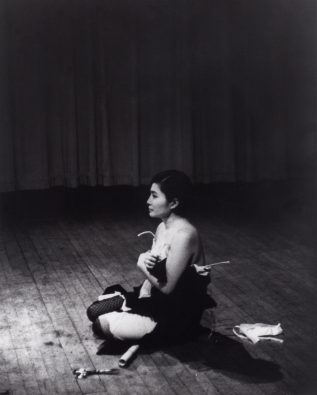

The same quality defines performance art. In 1964, Japanese-born artist Yoko Ono, who had audited Cage’s classes at the New School (the same course that formed the foundation of Coleman’s Curings), sat alone on a stage in Kyoto. She wore a dark suit and her hair was pinned behind her head. Next to her were a pair of shiny scissors. Her preliminary instructions for this piece were later outlined as follows:

Cut Piece First version for single performer: Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him. It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage — one at a time — to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them. Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. Piece ends at the performer’s option.3

As people from the audience approached her, Ono was stone-faced. She waited and watched as people snipped at her clothing, becoming more exposed to the audience physically and emotionally. Yet whatever discomfort she felt was masked.

Ono had a sense, I assume, how the first performance of Cut Piece would unfurl, still she couldn’t have predicted who would cut the straps of her bra with temerity or who would take only the smallest swatch of fabric. Different iterations — in Tokyo, New York, London, and Paris — have followed the same script, each inflected with nuances from the whims of the participants. They have all been as unique as the makeup of each audience.

Certainty cuts crossways from the agenda and intention of Cut Piece because improvisation and audience participation are integral. And so it goes with pregnancy: Vulnerability reigns, an insight I believe that Ono understood. Months before Cut Piece debuted, Ono had become a mother. She had a daughter, Kyoko Chan Cox, with her second husband, the American jazz musician Anthony Cox. Over a decade later, she would have a son with her third husband, John Lennon.

Perhaps the dearth of reflection on this beguiling period comes from the difficulty of portraying its complexity. The mystical phenomenon of carrying a child too easily crumples into treacle and the more colorful descriptions of the physiological changes many women face seem extreme, perverse, or at their worst, shameful. Women can’t bemoan the discomforts that accompany their privilege to birth new life, or so we think.

Time for introspection is both a luxury and a necessity of my vocation as a writer and artist — both positions, I cannot deny, are linked to being white and privileged. Perhaps pregnancy, left unexamined, becomes not only less bewildering, but also more mundane. Looking back on my first trimester, I was too easily swayed by the statistics and lists of potential problems rattled off by various doctors. Instead of believing in my own body’s capacity, I allowed fearful rhetoric to swallow me. How would I have fared if the first trimester had been celebratory instead of magnified by fears and medical statistics on the viability of my pregnancy?

Still change is rapid. A new day brings a foreign sensation — like the sudden gurgling, pulsing presence inside my uterus — or none at all. As my middle section engorges into a bulbous mass, I feel more animal and carnal than ever. Pregnancy forced me to exit the maze of detached thoughts and embrace a more intuitive, physical mode of being. To be present with my feelings of uneasiness and elation. To exist in the radical realm beyond reasonable language.

Writing about the novelty of a live dance performance in an era dominated by screens, John Cage said in his book, Silence, “Our intention is to affirm this life, not to bring order out of chaos, nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply to wake up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord.”4

At its best, my experience of pregnancy — the precarious performance of it — mirrors this idea. The past few months have been the ultimate affirmation of the life I’ve known and its myriad cycles. This time marks the hopeful beginning of one life and the willful resignation of many others.

Who will I be as a mother? I won’t know, but in the meantime, I often imagine myself climbing a tall ladder, peering through a magnifying glass, and reading the word “YES” printed on a piece of paper. Other times, I see a parade of crickets, exploding into a field like fireworks over a summer sky.

Inside a pregnancy and a performance, there is an anticipated ending, an expectant one, but in the meantime, everything happens. The only sure thing is that I will not remain pregnant forever.

* * *

Now on the other side of pregnancy, the contrast between any anticipated existence and my reality is extreme. My son arrived three weeks early and three days after President Trump had declared a national state of emergency because of COVID-19. The pediatrician and the few strangers we encounter wear masks and I suspect that my child may associate my smell with the stringent scent of hand sanitizers and other disinfectants.

During my son’s first week alive, winter ended and spring began. In the same way, people in this country and around the globe began to grieve a way of life that is no longer tenable. Reading this essay now, my experience of the postpartum period — compounded by the anxiety and eerie stillness of the pandemic — underscores the running theme of this essay. Like some women, I felt pressured at first to perform my pregnancy, as if for an audience. Reliving the early histories of performance art disburdened this idea and reasserted the value of presence. From the shaky beginning of my pregnancy to the claws of a pandemic, I am learning — and relearning — to be more attentive, curing myself in the sugary brine of the present.

This text was written from Winter 2019–Spring 2020, as a response to Jackie’s time as Critic-in-Residence with The Chart in Portland, Maine, in August 2019. During her time in Maine, Jackie met with artists throughout the state of Maine in studio and site visits and participated with more than a dozen artists, musicians, educators, and performers in John Coleman’s CURING: FORTH, discussed above. Jackie gave a public lecture at Able Baker Contemporary and ran a workshop on arts writing and the artist statement at SPACE.

- Abigail Cain, “A Brief History of ‘Happenings’ in 1960s New York,” Artsy, March 12, 2016, accessed January 4, 2020. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Cut Piece, Yoko Ono,” MoMA Learning, accessed January 5, 2020. ↩

- John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings, “(Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, 1961), 95. ↩

Jacquelyn Gleisner is an artist, writer, and mother. She holds degrees from the Cranbrook Academy of Art (MFA, 2010) and Boston University (BFA, summa cum laude, 2006). Her work as a visual artist has been exhibited throughout the United States, especially within New England, and internationally, in Italy, Finland, and Botswana. In 2010, Gleisner was awarded a Fulbright grant to Helsinki. Five years later, she traveled around Botswana through an artist exchange funded by the Art in Embassies Program. As a writer, Gleisner has been published in Hyperallergic, Art New England, Two Coats of Paint, The Arts Paper, among others. Gleisner was a regular contributor to four columns for the ART21 magazine for over seven years. In 2018, she founded Connecticut Art Review, a writing platform for the arts in and around the state with the twin objectives of focusing on underrepresented communities and raising awareness of pressing social, cultural, and/or political issues. She lives in New Haven.