by Gordon Hall

The Number of Inches Between Them is a new sculpture and performance project by New York-based artist Gordon Hall. The project is a continuation of Hall’s series of “replica” sculptures in which the artist makes doubles of accidentally-encountered one-of-a-kind pieces of furniture. The Number of Inches Between Them replicates a geometric stone bench located in the yard of a private residence in Clinton, New Jersey: the sculpture and performance are intended to be in conversation with Dennis Croteau, the little-known artist who designed and made the original bench shortly before he passed away from AIDS in 1989. The sculpture itself is offered as an architectural body, assembled and disassembled and brought into proximity with human bodies at various stages of vulnerability and transition.

Following the performance at the Winter Street Warehouse in Rockland, Maine, on August 11, Hall organized an evening of lectures and performances that took place at Hillside Farm in Camden. Building upon Hall’s ongoing project The Center for Experimental Lectures, the participants over the evening are members of Hall’s New York-based critique group that originated out of being performers in Hall’s piece STAND AND. This group has been meeting monthly since 2014 and has been the site of numerous conversations that have been influential over the development of The Number of Inches Between Them.

At the end of the evening, Hall, backlit by the warm glow of light emanating from the farmhouse, read a statement to the audience on the lawn. They reflected on The Number of Inches Between Them and the time during which Hall and the crit group were in residence at Hillside Farm. That statement follows below.

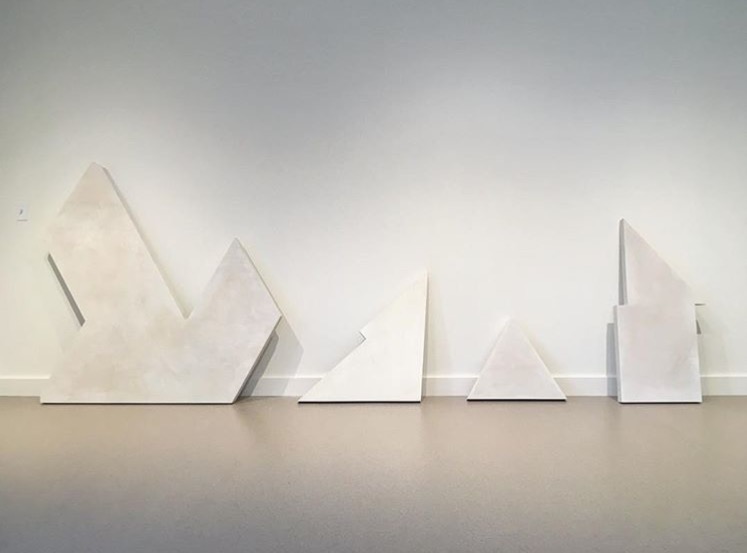

I made a promise to myself a few years ago that I wouldn’t make any more sculptures that I couldn’t lift by myself, a promise that I have clearly broken with the project many of you saw today called The Number of Inches Between Them. This cast concrete bench consists of eight panels ranging in weight from 45 pounds to 320 pounds, and there are two complete sets of these panels that comprise the assembled and disassembled version of the bench. All together, it weighs around 2400 pounds. At 45 pounds, only the smallest of the concrete components weighs little enough for me to lift it without help. Throughout making and transporting and installing this work, I remembered over and over again why I had made this promise about only making sculpture I could lift on my own: all of this weight produces in me intense feelings of vulnerability and powerlessness, often followed by rage. I can’t even turn the slabs over to sand the other side without asking for help, and whether this help is paid or offered as a favor, the helplessness I feel about tasks I cannot accomplish without my body alone hollows me out, and I alternate between a sadness and an anger that are echoes of experiences of powerlessness that are far removed from the current conditions of having made a heavy sculpture. The joy I feel at looking at something I made that I think is beautiful has been paid for in this case with months of the depletion of my sense of self-reliance.

I often hear art talked about in terms of expressiveness — as expressing the thoughts and feelings of the artist and communicating them to others. I am critical of this idea for numerous reasons that I won’t expand on here, but I will say that I have often felt underserved by the “art as expression” theory because it implies that I think and feel what I think and feel in an unconflicted and decisive way. It requires me to be internally consistent in ways that do not reflect my numerous experiences of deeply believing two utterly contradictory things, either simultaneously or in alternating succession. Many artists are involved in something more muddled than expressing themselves — in many instances it seems more correct to me to think of art-making as a process of trying to change our own minds about the things we are conflicted about. We make things to embody the positions we want to have. In this sense, making is not about expressing ourselves in a clear, correlative way, but more about trying to transform ourselves through physical experiences that force us to change shape in response to them. Another way of saying this is to say that people make things about what they want to believe, rather than about what they do actually believe. Or, that making things is about self-transformation. Or, since that word — transformation — is overused and probably too grand, I will say this: making things might be about nudging ourselves towards ways of being in the world that we both desire and are repelled by.

In the height of my fury about feeling so helpless and indebted to so many people who have helped me with this extremely heavy work, it occurred to me that I had inadvertently devised a project that put me into a relation to reliance on others in order to execute it. The feelings of self-reliance and control that have always been such a central aspect of making work for me are not allowed to be present in this project — by its design, although I did not intentionally pursue this outcome. The sculpture cannot be assembled without a team of seven people who all have to work together to lay the 320-pound seat down onto the legs that need to be simultaneously shifted into precisely the right location to allow it to snap together into a useable piece of furniture. These people not only need to be strong enough to lift the concrete panels but also need to work together as a collective body to negotiate the task of assembling it. Since the project’s inception I have been understanding it as a contribution to a conversation about bodily vulnerability and support, about our bodies’ relationships to objects and furniture in illness or disability, and hinging on the question of whether or not we have a collective investment in providing for one another’s basic needs. I made a bench that literally holds people up as a way of thinking about both material and less-material systems of support that make all of our lives possible in sometimes more and sometimes less visible ways. That the original maker of this particular bench was an artist who died of AIDS along with so many others at that time further pushed the investments of this project towards this line of thinking, since the AIDS crisis was, and is, such a blatant failure of institutionalized care for people who need it, while also emerging as a remarkable instance of smaller scale self-organizing and support.

I was thinking about all of these things but I did not realize until this week that the project’s critique of self-reliance and of the myth of able-bodied-ness was taking place on a much smaller scale in its fabrication and installation. In the midst of feeling so powerless in relation to all this weight, I realized that I had made something that forced me to be taught, yet again, that I need lots of many kinds of help. The sculpture itself was teaching me, with my body, the thing that I need to know: No one ever does anything alone.

Gordon Hall‘s The Number of Inches Between Them is on view at Steel House Projects through August 26, 2017. Hall performed at The Winter Street Warehouse in Rockland on Friday, August 11, that was followed by an evening of lectures and performances at Hillside Farm in Camden with contributions from Chris Domenick, Gordon Hall, Juliet Jacobson, Andrew Kachel, Millie Kapp, Stephen Lichty, RJ Messineo, Colin Self, Orlando Tirado, Mariana Valencia, and Georgia Wall.

The Number of Inches Between Them was organized by Elizabeth Atterbury and Meghan Brady. Support for The Number of Inches Between Them was provided by SPACE Gallery through The Kindling Fund.

Steel House Projects

639 Main Street, Rockland ME | 207.691.5864

Open Monday–Friday 9am–5pm and by appointment.

Gordon Hall is a sculptor, performance-maker, and writer based in New York. Hall has presented solo exhibitions at EMPAC (2014), Foxy Production (2014), Temple Contemporary (2016), The Renaissance Society (2018), MIT List Visual Arts Center (2018), and Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (2019). Hall’s sculptures and performances have been exhibited in a variety of group settings including Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2010), SculptureCenter (2012), Movement Research (2012), Brooklyn Museum (2014), White Columns (2015), Whitney Museum of American Art (2015), Hessel Museum at Bard College (2015), Chapter NY (2015), Art in General (2016), Wysing Arts Centre (2017), Abrons Arts Center (2017), Socrates Sculpture Park (2017), The Drawing Center (2018), David Zwirner New York (2018), and the Verge Center for the Arts (2019). Hall has organized lecture-performance programs at MoMA PS1(2012), Recess (2013, 2014), The Shandaken Project at Storm King Art Center (yearly, 2012 -2016), Interstate Projects (2017), Brooklyn Academy of Music (2017), Artists Space (2020), RISD Museum (2020), and at the Whitney Museum of American Art, producing a series of lectures and seminars in conjunction with the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Hall’s books include Reading Things—Gordon Hall on Gender, Sculpture, and Relearning How To See (Walker Art Center, 2016), AND PER SE AND (Art in General, 2016), Details (Walls Divide Press, 2017), The Number of Inches Between Them (MIT, Printed Matter, 2019), and OVER-BELIEFS, Gordon Hall Collected Writing 2011-2018 (Portland Institute for Contemporary Art/Container Corps, 2019). Hall’s work has been covered in Artforum, Artsy, Art in America, V Magazine, Randy, Bomb, Flash Art, Title Magazine, and Mousse Magazine, and they have published essays in Theorizing Visual Studies (Routledge, 2012), Art Journal (2013), What About Power? Inquiries Into Contemporary Sculpture (SculptureCenter/Black Dog Press, 2015), Documents of Contemporary Art: Queer (Whitechapel/MIT Press, 2016), and Art in America (2018), among many other contexts. Hall has been awarded residencies and grants from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Triangle Arts Association, The Edward F. Albee Foundation, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ACRE, Fire Island Artist Residency, and Foundation for Contemporary Arts. Hall holds an MFA and an MA in Visual and Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA from Hampshire College. Hall was a 2019-2020 Provost Teaching Fellow in the Department of Sculpture at Rhode Island School of Design and will be resident faculty at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in the summer of 2021.

Gordon Hall is represented by DOCUMENT.