In early April, the Portland Museum of Art and the 1932 Criterion Theatre in Bar Harbor will be screening Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler’s River of Fundament: a three-piece epic opera of regeneration and rebirth. Loosely based on Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings — and borrowing its structure — River of Fundament combines documentary footage and live-action cinema over eight years and three locations (Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York). Douglas W. Milliken, writer and author of the recently-published Cream River, and Jenna Crowder, artist and co-founder of The Chart, sat down to discuss the films.

As in the film, this conversation discusses graphic subject matter; what follows below is an edited, condensed version of the conversation (sparing you, dear reader, a transcript as long as the films themselves). Please note that while we’ve tried to be sensitive to edit out major spoilers, there are probably a few things we’re giving away, too.

(Why) Does River of Fundament Matter?

Douglas W. Milliken: One thing I was thinking about — and this was even before we saw [River of Fundament], when we were trying to figure out how we wanted to go about this whole process — you had mentioned how, regardless of how you personally feel about Matthew Barney, you think this is an important thing, that he is an important artist, and I’m curious what that actually means. Why is this important?

Jenna Crowder: I feel like my experience of the film was shaped by asking myself that question. Regardless of how I feel [about Barney the man], Barney is an important artist: the scope and depth and reach of his work. There’s no way I can dismiss it. But I do think that it’s important [to ask] with every new work, “Is this important or not?” And also, can a really important artist — in the same piece — make something that’s important but also a total failure? After reading [Benjamin DeMott’s 1983 review of Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings], there is so much more paralleling that.

DWM: Yeah, you could just as easily be talking about Ancient Evenings. That was a novel that Mailer spent over a decade writing. That’s a significant portion of his life and his imagination and resources and research going into a project that, ultimately, most people didn’t like. There was an interesting point in DeMott’s review, where it talks about how the first ninety pages of the book are this exquisite, beautiful thing, and then it goes off in this other direction, which I think is also paralleled in the film, where the first twenty minutes of the film are operating in a much more highly symbolic, less literal level, and then it shifts gears into [something] more expository — as expository/narrative/linear as Barney can get. This is a biopic and it’s also an adaptation of this sprawling, 900-page novel. It’s ambitious to try and do both at the same time. Can you illustrate someone’s strengths and shortcomings in a way that is honest without being apologetic, without defending the negative choices? And I’m not sure what my answer is.

JC: I am not particularly sure why Barney [chose] to do Ancient Evenings. There are so many different reasons — like Mailer being involved in Cremaster — but it is interesting that Barney is taking Mailer and putting him in the steps of reincarnation. But I’m also trying to figure out, could it could be any other thing?

DWM: Oh, absolutely. Ancient Evenings, using that as a starting point, on the one hand seems like an unusual choice: why this of all of Mailer’s work? But throughout all of the Cremaster Cycle, there’s repeated and almost obsessive focus on not just occult and mythological imagery but specifically Masons, Freemasons, and how a lot of the basics of Freemason society is founded on ancient Egyptian mythology and beliefs. So there’s a pretty clear connection there. It makes sense that this would fall into [Barney’s] sphere of interest. [Milliken’s note: this assumption, it turns out, is 100% backwards according to an interview between Barney and Charlie Rose.] But also, in the same way that Hemingway— In this film, Hemingway exists so that Mailer can exist. There is this figure that came before that mirrors a lot the interests and is sort of a mentor. And I think, in a lot of ways, Mailer may be that for Barney as well. Because there are so many overlapping interests, like the exploration of the male identity and masculinity being the most blatant and obvious. But also the artist as not just an art-making spectacle. Like Mailer with his famous boxing match, and right after Executioner’s Song was released, there was a prisoner [Jack Abbott] that started writing to Mailer and they began this correspondence that eventually led to Mailer petitioning for this guy’s parole and release, and once that happens, six weeks later, the guy murders someone and ends up back in jail. There’s this element of making your life a spectacle. You’re not just an artist making a particular art but doing weird shit out in the world [or, alternately, how you live your life becomes an extension of your art], and I think that’s something Barney would definitely identify with. And I think also, there was some element of friendship, and I think that’s the thing that became most pronounced by the very end, when the step team enters — it’s when the second iteration of Norman is about to become the third iteration — that was the moment that was most emotionally poignant for me and that’s when it was most clear that, regardless of whatever else this movie was, it is a love letter to your dead friend, someone you love very deeply who is gone. I found that to be very poignant and very striking. So these are multiple reasons why Barney would make this massive, sprawling project about the life of Norman Mailer versus any other author or any other book by any other author.

That opens up another question for me. So he made this thing, among other things a love letter to his dead friend: is that important for other people to bear witness to?

JC: There are so many instances of that, where artists reveal their relationships through art or letters, blatantly or not. I think that creates a really rich lineage of how people affect and influence one another.

DWM: And then thinking about it in terms of monument. You can see a memorial sculpture and have a completely aesthetic experience with it, and that is complete and all you necessarily need. But you can also do that research. What is this a memorial to? Who is this figure? What is its circumstance? In the same way as doing the research to find out what all these symbols within the film mean, it can enrich your experience.

JC: And also, because it’s the structure of an opera, there is so much that automatically necessitates [that research]; you’re not going to get everything immediately all the time. It’s on you to do more research, it’s on you to look up the libretto-slash-script in this case, it’s up to you to understand the arc of this story before you get there so you know what’s going on. Which I think is the amazing thing about the structure of opera, and actually pretty amazing thinking about all of that in terms of what Barney is doing.

Sex vs. Pornography

JC: There are lots of countable instances. I made note of the number of ball sacks, number of erect penises, number of flaccid penises, number of guts, number of labia, breasts, anuses, the number of times I wrote “oh my god, UTI” in my notebook…

DWM: I think the idea of pornography, obscenity, profanity does need to be addressed.

JC: Yeah.

DWM: I’ll let you start.

JC: Yeah, it’s a good question. I ran into Jon Courtney the day after the film — he’s now doing the screenings programming at the PMA — and they’d been trying to figure out how to word the warning so that it doesn’t scare people too much. I think sometimes people assume the very worst and then miss out on a lot of great things […] He was asking how the rest of our screening [of RoF] went, and I was thinking by typical cinematic standards it is totally pornographic. His immediate question was, “Was it consensual?” And I was like, yeah, it totally was. So much so that I made a note about how both male and female pleasure are shown equally, maybe even more siding on the side of women’s pleasure, which I thought was awesome. There are totally these pornographic moments in it, but no one is having a bad time. There’s no rape at all, which is like, thank god, because it seems so normalized. Even on TV, all these crime shows, it’s all about sexual violence, which is totally absent from this. There is a lot of nudity, but there’s nothing necessarily wrong with nudity, and there are a lot of bodies covered in shit and boils, and they are still pleasurable bodies. Which I think is great, and also so ridiculous. In context, it’s seen as no big deal, which I also appreciate. Like, yes, people have sex. People do all sorts of things. People are into really weird stuff. And it’s all totally presented as normal and consensual and enjoyable.

DWM: In thinking about interpreting it as obscene or there for shock value versus the meaty, honest, viscerality of human experience, I feel it’s less about profanity and more about prudery, which is to say prudery is one’s ability to be offended. Where profanity is the ability to be offensive, prudery is to be offended. What is normal for some people is offensive to someone else, and sex is one of those issues that people can get very offended and scandalized by seeing depicted, as if they’ve never had it before or experienced any sort of sexual pleasure that isn’t described in a text book.

JC: Is that even pleasurable, though?

DWM: Right. Yeah. So to be scandalized is to have laid bare what you would like to keep secret. You don’t want to acknowledge whatever secret desire you may or may not have. And, to tie into what you just said, it’s all normalized. There are instances that are — I want to say Baroque — in how they’re composed, which makes it a little over the top in an aesthetic way, but as far as subject matter, it’s very normal and honest. And I think, where it can be said in Mailer’s Ancient Evenings, he was using the mythologies and stories of ancient Egypt as a way of understanding his own life and his own ambitions in his career, you can also say Barney was doing that, using Mailer’s work as a way of understanding his own life and career. But beyond that, this is also a story of rebirth and how the final rebirth isn’t into a new body but into the earth. There’s the reprise from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass where he’s talking about how you’ll find me in the dirt in the soles of your boots1, being reborn as the vegetable babe with the green grass as the hair of the grave2. You become a part of the universe as a whole. So if you’re going to talk about that, you need to acknowledge that sex is a big part of existence. And just the same way that there’s all these different cultures represented, you can’t talk about universal rebirth and only have white guys in America. You miss your own point in doing that. It has to be multicultural. It has to be from the most beautiful compositions and beautiful parts of nature to people covered in shit licking each other’s assholes. You can’t have one without the other.

JC: Yeah. And I think it’s interesting, too — symbolically, visually, aesthetically, and also immediately — Barney’s Apprentice3, looking into the toilet bowl, pulls out a big turd, gold leafs it, puts it back, and when he turns around and Mailer is there, there’s a close-up of this gold-leafed quickly-erecting penis that’s right next to this breathing, bubbling colostomy bag. It’s more complex than, “these will be aesthetically nice if we just put this gold foil on it.” I think it’s taking a look at how we’re evaluating sex and desire as, oh it’s gross, oh it’s beautiful. And even that’s a little simplistic and binary, but it’s setting us up for how we view the rest of the six hours.

DWM: In much the same way as the introduction to Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia serves as an expressionistic summary as to what the rest of the film will be, the introduction to River of Fundament operates in the same way.

[There’s a whole sequence of highly-symbolic fighting and sex] and it seemed to me that there was a unity between art and language and violence and sex. The ecstasy of art is the same as the ecstasy of language, the same as the ecstasy of violence, of sex, of eating. There are these lines that are drawn between them that seem very firm: sex and violence are not the same thing. But the sort of ecstasy you feel in those moments is very similar. The same as gorging on food or being blown away by an aesthetic experience, which again, I think that’s a way of illustrating the fight to be reborn into the universe.

A Question of Appropriation

JC: So this idea of Ancient Evenings and Mailer taking the Egyptian culture and basically — obviously, I haven’t read it, but in reading the reviews of it — it’s this idea of Mailer taking on Egyptian culture but still being very stuck in his own [time and place], so the reader is seeing ancient Egypt through his lens; it becomes his world that he’s putting on another culture, which is a very complicated thing.

DWM: Or, alternately, using this other culture as a way of trying to understand his own career and himself.

JC: I don’t know if I see a difference yet. But I’ve been thinking about that. Here is Barney recreating someone else’s work and taking that [cultural] aspect even further and that’s the part where it feels complicated to me. Is an artist absolved of any responsibility in portraying that again? I don’t want to be unnecessarily accusatory but I do want to investigate it a little bit and not be dismissive because the piece as a whole is really engaging and beautiful. And it’s this ode. It’s sort of a weird place to be stuck in.

DWM: I’ve been thinking about that. While we were talking during the intermissions about the idea of cultural appropriation, I think the way you had defined it then had to do with using superficial details of different cultures without really acknowledging or understanding or knowing the fuller depth.

JC: Yeah, I think it’s that and also taking those cultural references and dismissing or being able to walk away from the people and the context that got [you] there, you know, there’s an element of privilege there to be able to adopt these things and not have to be subject to any of the consequences of actually having that as your identity, if that makes sense.

DWM: I think so. I was thinking about that a lot re-reading the script. In the LA scenes, there’s a lot of Latino day workers and a mariachi band and there’s the vocal soloist, Lila Downs, who I didn’t know who she was [until I looked it up] and she’s not only this phenomenal vocalist who sings in six or seven different languages, mostly indigenous Central American languages, but is also a very out-spoken indigenous-rights activist. I don’t think that was an accidental choice that she’s being cast in this role. And I see that a lot throughout the film. Every single detail is so considered and none of it is superficial. So while Barney can’t necessarily identify as any one of the cultures that are being represented, I don’t think those cultures are being used. It does seem to me that it’s very intentional.

JC: I think it’s a critical question to ask. Especially because I think the way Barney is using all of this is, it’s himself, but he’s also referencing the book so it becomes that much more layered. But it is hard not to think about parallels between the day laborers pulling a car and thinking about the structures of Pharaonic Egypt and the question of slavery. So it also becomes a political statement.

DWM: And then, shortly after that [scene], there was this slow panning of this mural of autoworkers on an assembly line, and most of them are immigrants, and the movement of the car down the assembly line is almost identical of this moving of the funeral car. Every now and then there’d be certain details where I was like, I’m not getting the full cultural connection here. Then while I was going back over the script, I realized what I was feeling had [less] to do with what Barney was doing and more to do with my own ignorance of these cultures and all of the other references being made within the work. And I found that over and over again. My discomfort came from my own ignorance, not from what Barney was doing.

JC: Yeah, and that, I think, is totally crucial. I recently read an article where [Moze Halperin] was taking a look at Ai Weiwei and M.I.A. and cultural appropriation. It was kind of perfect timing for that to come out when I’m thinking about appropriation in relation to, specifically, this piece. Halperin proposes this: “At this point, if an artist so much as finds themselves in a place that isn’t their country-of-origin in their work, they will, somewhere, be accused of the art-crime of appropriation. And normally, it’s a particularly appropriative look if the artist themselves inserts themselves centrally in the narrative of another culture and makes the people around them their props.” As Halperin suggests later, am I trying to force artists, Barney in this case, into these boxes of where they can and cannot make work and where they can go and can’t go, or am I actually trying to figure out [how] I am being responsible in what I support and what I write about and what I critique. I don’t want to dismiss that because then that’s also my own ignorance, right?

Trusting the Artist

DWM: Your preconceived notions of this are not going to serve you in the end. […] When we were first talking about doing this article, it seemed to me that if you’re familiar with Barney’s work, you’ve got your mind made up and this probably won’t change it. And I don’t know if that’s necessarily true now, after having seen it.

JC: [Barney, in general,] comes off as being a total genius but also as kind of misogynistic, and to be fair it’s been a while since I’ve seen the Cremaster Cycle. But I was thinking particularly about True Detective, where the whole first season and a couple episodes into the second season, I was literally like, why am I watching this? I can’t not watch it for some reason. Because it’s so beautiful, because there’s something in it that’s compelling me to stay in it even though I really don’t want to. And then something so immediately changed and I realized, oh my god, this is such a parody of what masculinity is and how terrible it is4. I could no longer see it as taking itself seriously — the characters did, the writers did not. And that’s kind of how I entered River of Fundament, thinking that I might very immediately have reactions to it, especially after the first part where nothing has been resolved. But they aren’t idiot filmmakers. And I think that that really did help my viewing, to think that, okay, I trust the artist enough or the filmmakers enough and the producers enough that they could portray despicable people — for a greater good. And I think that certainly comes across in River of Fundament, both the exaltation and the total critique of Mailer and his work and also of industry, especially the auto industry. And I think all of those contradictions exist there in so many ways, and yeah, I think it goes back to what you were saying about how you approach it with this prudishness or — what did you say? Prudery or—

DWM: Prudery or profanity.

JC: Profanity, yeah, and what it says to be a viewer with all these things you’re bringing to it, but also what it says to be the artist making this — how do you meet and how do you have this conversation with art. And are you open to having a conversation with it or not?

Creating an Opera: Music + Collaboration

JC: We need to talk about the music. Because it is an opera, because it was so closely a collaboration between Barney and Jonathan Bepler.

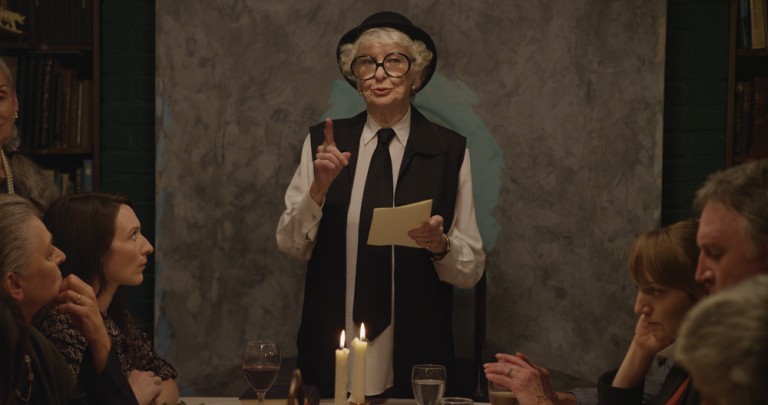

DWM: When I saw the Cremaster Cycle, especially parts two and three, those were the ones that most affected me, and I noticed that a lot of the time, the music was carrying the film. There were sections, especially of Cremaster 3, that were so slow to the point of almost being boring, and it was the musical elements that kept it afloat. And I think with River of Fundament, the creative relation between Barney and Bepler was much more balanced and much stronger. They’re credited as both having made this thing. It’s not a film by Matthew Barney with a soundtrack by Bepler, it’s their twin creation. And I intentionally didn’t read up a lot about River of Fundament beforehand because I didn’t want anything clouding my expectations or judgment, so it was a fun discovery for me part way through [to realize] this is an opera! This is an opera made for the screen. I mean, it was also five performances: the film is documentation of these live performances. But that moment where it begins that transition — I can’t remember the woman’s name — but she’s giving the first of the eulogies—

JC: Oh, Elaine Stritch.

DWM: Yeah. And the musicians are tuning their instruments, and that becomes part of the composition, and as she’s reading from Ancient Evenings, she begins singing certain words, not entire phrases, but a word here and the word there, and it gradually eases you into this operatic world. From that moment on, and increasingly throughout the film, there is less and less spoken dialogue and more and more sung, to the point near the end, it’s over-the-top now, it’s reached the level of opera that most people think of as opera and roll their eyes at, it’s overwrought completely.

JC: And, in context, everything is overwrought in that whole third part. So it’s gearing up to be so over-the-top and too much, like everything is too much.

DWM: Which again, talking about the ecstasy of language, violence, art, sex: to take any one of those and go too far with it becomes the same ridiculous circus. When they’re all out of balance, it’s a mess.

JC: And that’s interesting in the whole scope of things. Starting out…not austere, but compared to the end, it seems that way. Very beautiful. And it felt like a very gradual crescendo, to the point where eventually I realized it was so absurd and I had to wonder where I would draw my own line. But I couldn’t let go. I couldn’t turn away. Anyway. That’s a tangent.

DWM: I think that illustrates the point, though. It’s not really a tangent. This is too much, but I’m not turning away. I’m still interested.

JC: Yeah, because I’ve been gradually eased into it.

DWM: Right. Which is how it works. That’s the trap of overindulging in any aspect of human existence. You can’t really determine the point of, this is the line of good taste and I missed that miles ago. You never know where the point of no return is until it’s lost behind you.

JC: Yeah.

DWM: So you just gotta keep going forward.

JC: Exactly. And I wanted to! Going back to the music, though. It was in the second part in Detroit that I really noticed how incredible it was. Nephthys [played by Jennie Knaggs, also from Detroit] just has this incredible voice and she’s calling out to all the other officers and forensic scientists and that call and response was so beautiful and so animalistic and also obviously mimicking an order and response, this almost militaristic sense about it. But the tonalities and guttural-ness and the whooping — and the precision and mastery of vocal work — blew my mind. And realizing that that had also been happening on much more subtle, almost conversational levels before, like in the apartment. All the vocalists that are around the musicians having these little drawn out conversations that in the end become total nonsense babble but still, through the voice as an instrument, accompanying everything else that’s going on.

DWM: Especially Phil Minton’s totally weird, babbling nonsense. He becomes the soloist of that, where he’s like burbling like plumbing. Meanwhile, the keyboardist [Dr. Lonnie Smith] is at the same time playing these really low things on his organ that are the same sort of bubbling. So it’s still tonal, it’s still musical, but it’s the gross murmur of a million voices saying nothing. Bepler has this amazing ability of arranging dissonant notes together in a way that is not aggravating or discomforting but is beautiful and musical, you can still feel melodies moving through these dissonant tones, and it was amazing seeing how that translated to a much more vocal composition. There’s singing in Cremaster 2 and 3 and especially in 5, but it felt so much more masterful [in River of Fundament], especially where it was an array of voices and not just a few voices. Especially the “Ballad of the Bullfighter,” where that’s such a pop song, it’s so catchy and so beautiful, but the chorus of ukulele players are playing a bunch of different chords. As far as [being] classically musical, it’s not musical, it’s a mess. But it holds together. It’s just confounding. It’s another hallmark of Barney and Bepler’s collaborations, to make these things that are just totally confounding and yet riveting. Not understanding what I’m seeing and hearing or not understanding why what I’m seeing and hearing is so compelling, why I’m drawn to a thing that natural instinct tells me to turn away from. You know, a turd wrapped in gold foil shouldn’t be beautiful. A fountain of green diarrhea shouldn’t be beautiful.

River of Fundament

350 minutes

Directed by Matthew Barney

River of Fundament screens at the Portland Museum of Art April 1–3, 2016, with the following schedule:

6:30 p.m. Friday, April 1 — Part 1

2 p.m. Saturday, April 2 — Part 2

4:20 p.m. Saturday, April 2 — Part 3

11:30 a.m. Sunday, April 3 — Part 1

2 p.m. Sunday, April 3 — Part 2

4:20 p.m. Sunday, April 3 — Part 3

Portland Museum of Art

7 Congress Square, Portland, Maine | 207.775.6148

Open Tuesday, Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday 10am–5pm, Friday 10am–9pm, Third Thursdays 10am–8pm. $12 adults, $10 seniors and students, $6 youth 13–17, $5 surcharge for special exhibitions. Free for children under 12, members, and everyone on Friday evenings 5pm–9pm. Weekend film passes are $15 ($12 for PMA members). Individual screenings are $8 ($6 for PMA members).

River of Fundament screens at the 1932 Criterion Theatre on April 3, 2016, presented in conjunction with SPACE Gallery & Portland Museum of Art.

The 1932 Criterion Theatre

35 Cottage Street, Bar Harbor Maine | 207.288.0829

Tickets for River of Fundament: Balcony, all Seats $15; Orchestra, Adult $12; Orchestra, Student/Senior $9

- “I bequeath myself to the first to grow from the grass I love, / If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.” ↩

- “Or I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the vegetation. / Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic, / And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones, / Growing among black folks as among white, / Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive then the same. / And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves. ↩

- In the film Matthew Barney plays “The Entered Apprentice” ↩

- Crowder’s note: I’m talking specifically about the toxic, misogynistic, macho kind of masculinity — not masculinity in and of itself. Alanna Schubach outlines my feelings better than I can in her piece for Jacobin, “The Trouble with True Detective“. ↩

Douglas W. Milliken is the author of the novel To Sleep as Animals and several chapbooks, most recently the collection Cream River and the pocket-sized edition One Thousand Owls Behind Your Chest. His stories have been honored by the Maine Literary Awards, the Pushcart Prize anthology, and Glimmer Train Stories, and have been published in Slice, the Collagist, and the Believer, among others.