by Dylan Hausthor

On my way to meet with the photographer Jocelyn Lee at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, I stopped at a cafe to get some tea. She was there waiting for a sandwich and we got to talking. A short time later — during our brief walk back to CMCA together to discuss her solo show, The Appearance of Things — I realized that we had already talked about love, money, death, depression, and happiness. The big questions seem to always be close to the top of her mind.

In a recent interview, the photographer Ron Jude spoke about his documentary project Nausea, saying that he “wanted to make another kind of photograph, one that moved beyond the literal and prosaic, yet didn’t abandon the essential, indexical qualities of the medium.” The Appearance of Things does just this, recalling the Modernist understanding of metaphor and beauty without ignoring the rationality of her camera. There is an aggressive humanism in how Lee wields her lens, and a willfully embellished sympathy and glamour to her portraits, landscapes, and still-lives.

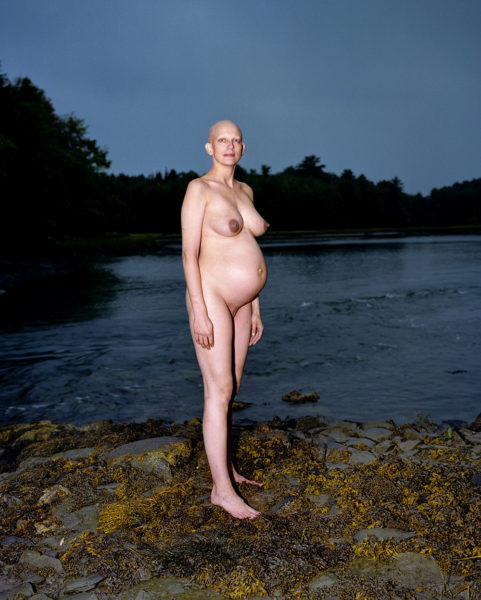

The dozens of Lee’s photographs, which fill a gallery at CMCA, reinforce my feelings of romance in her process. Larger-than-life portraits are woven through photographs of a natural world ripening and decaying. All of the portraits are of women, their ages ranging from near-birth to near-death. Most of these women are floating, either literally or figuratively, in natural environments. Nature and portraiture cross-pollinate in this work, the power dynamic of which leaves me unsure if the humans in these images occupy their environment, or vice versa. We sat on the floor of the gallery to talk about putting the show together, her orientation as a mid-career artist, and how the grammar of photography functions for her.

Dylan Hausthor | I think I’d like to start at the very beginning. The title of the show.

Jocelyn Lee | The Appearance of Things.

DH | Indeed. I was almost surprised by it. My first reaction was that it seemed a little tongue-in-cheek, an intentional oversimplification of what photography does, but it’s also very open-ended.

JL | The way that I think of it is from an existential perspective of the Buddhist concept of things arising into being and disappearing into nothing. Two sides: light and dark, life and death. It’s so much about the celebration of the sensual world, and threaded through that world is the inevitable decay and decline of everything that is living. We’re seduced by it — and flesh. The flesh of the apple, the flesh of the flower, the flesh of the person. Then everything disappears.

I use color metaphorically and symbolically, like the way I use white in the show. White can be seen as referencing purity, cleanliness, absence, but also beings drained of life: the frozen tundra, the Arctic, or even that woman who looks like a pilates victim. Her room is so controlled, everything in her environment is so controlled. She is white, her hair is white, her skin is white, her muscles are taut, her environment is white, but then she puts this really red lip on. Like that’s the most living thing on her. So I’ve also really been thinking about color as a symbol, and in pairing her with these dogs, who are so urgently eating to survive. And the red of their tongue. These are the things that I thought about while hanging the show.

DH | In the intro to the show, you wrote a little bit about “mingling” of genres. When I think about mixed genre in photography, I think about storytelling devices, but the way you wrote about it seems to be more about physicality, less about narrative. How did you think about narrative when putting together the show?

JL | I’m hoping that this idea of the arc of life — from beauty to death, from nothingness to the peak of blossoming, and to decline — is the thread between images. But urgency too, like the urgency to eat like that dog. I was looking at Hieronymus Bosch, and these essential elements — food, sex, breath, even vanity and ego. That’s what drives me, as well as the sensuality of our bodies and a central experience. Like the woman floating in the water. Is she giving birth to the seaweed? Or is she being birthed by the seaweed? There are references to painting, too. I think about painting a lot, just because it’s fun to do if you’re thinking about the history of pictorial representation. So that one is like Ophelia. I wanted the black wall [two of the gallery walls in the space are painted black] to have these tableaus, almost as if we’re floating above the Earth and these are moments of illuminated events that are happening simultaneously, connected only by the fact that they are happening on Earth, but in distinct habitats and environments.

DH | How does time work into that?

JL | That’s a really good question because it plays into how pictures are made. I think these pictures take a very long time. The only picture here that is immediate is the one of the dogs. The other pictures feel very slow.

DH | Yeah, I was surprised to hear you talk about urgency.

JL | Yes, I suppose I mean urgent as existentially true.

DH | As in survival?

JL | Yes! Urgency as a lifelong thing. We need sun, we need earth, we need food. Our skin burns. These essential facts. It’s simple, but when you think about it, this is a big, deep concept: we are of the same material as everything on Earth, just in this container of the human body. I love photographing animals, which is partly why I love your work so much. I’m dying to make more animal pictures; we coexist with these things!

DH | Right. They’re very base.

JL | Primitive. I studied philosophy as an undergraduate, as a double major with photography. I was a terrible philosophy student, but I loved thinking about these ideas, particularly existential philosophy. How we make meaning in our lives; what are the essential concerns? Vanity I think is very interesting, because it’s the counterpoint of all of this. The inevitable decline. Like photographing old bodies, aging bodies, bodies that respond to gravity. The honesty of that is really important to me because it’s everything that we try so hard not to admit.

DH | Well let’s talk about nudity. I’m thinking about your work and the history of the female body: it’s so serialized in this collection of work that it doesn’t feel gestural as much as a conceptual tool — which maybe speaks to the existentialism?

JL | To me, it’s all about the body. I used to be a dancer, a long time ago. I feel like that’s the starting point: the human body in space. And narratively it’s about nakedness. There’s so much of a story there — the minute you ask someone to take their clothes off you’ve got the narrative of their body. Whatever they’re carrying with them. The dynamic between you and the person who’s naked and the awkwardness of that. The expectation, too — why does someone do it? There are people who do it because they’re vain and that vanity shows. Which is its own interesting thing.

I try very hard to get to a place where [the models] forget about me. They never forget about me, but they do often get to a place where they’re bored. It’s a long shoot and it’s a heavy camera. This picture of her in the water — she was in that water for 45 minutes. There’s a point where she’s not thinking about me so much. She’s cold, she’s going through whatever she’s going through. They are directed pictures, but I don’t want them to be really mannered.

DH | Why not?

JL | So that’s the critical question: when is a picture too formally controlled or mannered, and when does it have life in it? I struggle with that constantly. We’d have to look at a contact sheet and ask, why choose this one and not that one? It takes me months and months to choose a picture, and ultimately what I reject is the one that feels too mannered. It doesn’t feel authentic enough. Which is a funny thing to say because these are directed. It’s a very tenuous line.

DH | I think you can find that authenticity in performance too.

JL | Yes, I think you can. That’s the difference in good and bad performance art, too, when something raw is happening.

DH | Do you feel any sort of journalistic integrity? Is it important that there’s a truth to the pictures?

JL | For this body of work, I’d say no. When I was first starting out and didn’t know what I wanted out of photography I did a documentary on teenage parents. It was one of those projects that I made when I was young and was trying to figure out my place in the history of photography. Interestingly I used the same camera that I use now, but I really didn’t like doing the documentary. At the end of the day, I felt an incredible sense of responsibility to the subjects.

DH | I think about this all the time.

JL | The story that I was telling was not the story that they wanted to be told. I don’t think I’ll ever do that again. It’s just so loaded. Here I feel like I have total freedom. This is metaphorical fiction.

DH | I’m thinking about Lauren Greenfield, Laurie Simmons’ new work, Cindy Sherman’s incredible Instagram, Nan Goldin’s newfound significance, and I find it almost disheartening that feminist imagery from twenty years ago is equally important today. How do you feel like you fit in with mid-career feminist artists?

JL | I’m not sure. I don’t totally know how to answer that, because my work, on one hand, is philosophically humanitarian. It’s about living, dying, and mortality. It’s pretty broad, not specifically about the rich or a certain class or a specific gender. It’s much more about the essential questions that apply to all living beings. But at the same time it does ask for a radical empathy for the human body in all its forms and states, so in that sense it is feminist. It is vehemently anti-vanity culture specifically as it refers to images of women.

DH | It is all pictures of women though.

JL | It is. So, yes, I think that from the perspective of showing the real body as it ages, that has always been the cornerstone of my work. I do photograph men, they’re just not in this grouping. Which I think is actually a weakness; I think there should be some here. But I think the work is absolutely about the female body and honestly showing it through stages, which is pretty invisible, pretty hidden.

DH | Does it feel any different to take nude portraits of women now then it did ten years ago?

JL | It doesn’t feel different to me. I think it’s still taboo. My Instagram was shut down because there was an elderly woman on it standing on the beach. I’m surprised by it actually. I’m really surprised.

DH | So maybe it feels different to show, but not to make?

JL | When I was in graduate school I was taking pictures of a pregnant woman, just thinking that I had never really seen it. It was the next generation above me, and I just wanted to see what pregnancy looked like in a frank and honest way. Not romanticized. It was shocking, in school, how few people had seen naked pregnant women. In some ways, I only photograph what I want to see, what I want to learn about. So now I’m getting older, so photographing older women has a more personal curiosity connected to it.

DH | This is a decade of work right?

JL | It is. The bulk of it was made in the last five years. It really happened when I moved to Maine, which has made it so much easier for me to photograph in my backyard. My yard became my studio.

DH | I was wondering about culture in this collection of images, and the minute references to any sort of time period. The lego spaceship, the headlamp, and the clawfoot tub—

JL | I think the better way to say it is that I really try to strip those things out of it as a way to open the narrative. If you think about documentary as grounding you in a place, a time, a story, and an individual, I instead try to open these. I don’t want that grounding because I don’t want that specific narrative. I was even debating if any of these subjects should be looking back at the camera. In the newest pictures, they’re not. The body is getting more and more into the landscape. I thought that I could include some of these that look more like traditional portraits, looking back at the viewer and the information and space that grounds you in time. I’m really aware of that, and it’s minimal because I want it to float in a more universal time.

DH | The last, obvious question for me, is about your relationship to death.

JL | Because it’s not here?

DH | No, because I think it’s very much here.

JL | Oh, good. I was thinking about putting in a picture of my mother after she died, but thought it was too heavy-handed. I photographed her from her late 30s until she died at 69.

DH | There are many more oblique references to death here: rotting apples, decaying fruit. How does control play into that? The trope of death is a lack of control, but the craft, process, and display of these images are very controlled.

JL | It’s an attention that, as a photographer, I have to think about a lot because my approach is very formally controlled. At their weakest, the pictures are too controlled, and I’m very conscious of that. What I’m trying to do in this work — through juxtapositions and pairings — is to break down some of those still edges. Open up the frame. Have associations. I’m hoping that those layers of association come in so that you don’t get stuck in the rigid confines of one framed photograph. I see pictures all the time that are so formally controlled that they’re dead. There’s no punctum, in the Barthesian sense of the word. How do you describe that? There’s nothing raw there, nothing living. And it’s hard to do when using a medium format camera on a tripod.

DH | I find that all of my best pictures are unexpected.

JL | My approach is directorial, so how do you give air and life into that which can be so dead? That’s the collaborative piece — I have to loosen my process to recognize when something much more interesting is happening than I imagined would be. Then, of course, creating a show is such a different process in itself. I end the show with a picture of my mother with her eyes closed. Almost as if she’s dreamt this whole thing.

Jocelyn Lee’s The Appearance of Things is on view at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art through October 14, 2018.

Center for Maine Contemporary Art

21 Winter Street, Rockland, Maine | 207.701.5005

Open Wednesday–Saturday 10am–5pm and Sunday 1–5pm. $6 general admission, free for members and children 12 and under.

Dylan Hausthor is a photographer, filmmaker, and editor based on a small island off the coast of Maine. His work is an act of hybridity–an effort to render field recordings into myth. Interested in small-town gossip and the fragility of journalistic truth, his work examines the borders between autobiography, fiction, and fact. Hausthor’s work has been showcased nationally and internationally by the Aperture Foundation, Ain’t-Bad, PHMuseum, Humble Arts, Nava Print Studio, Gomma, Yogurt Magazine, Void, and LensCulture. He founded Wilt Press in the spring of 2015 and is a current grantee and previous artist-in-residence at the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation in Rockland, Maine.