by Julie Poitras Santos

We must realize that the world as it is isn’t worth saving; it must be made over.

— John Rice

Upwards of 70 people drifted through the galleries and collected around the grand piano underneath Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting (Four Panel) from 1951; shortly, Elaine Rombola would be playing selections from John Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano. Gallery guards tried to organize the crowd of music aficionados and museum goers, asking us to “stand behind the line” which, frankly, was unclear: the cement floor has many lines at that corner of the gallery, and “behind” could be in any one of a few different directions. People sat down on the floor cross-legged, and scooted forward toward the piano. A more formalized audience sat on folding museum stools in one corner. The rest of us, standing, shifted back and forth across those “lines” — trying not to topple onto the expansive dance floor, trying to get a clear sight line, making way for wandering viewers, humoring the flustered guards. To top it off, during the performance, one of the guards dropped his cellphone to spectacular clatter and effect, parts flying in all directions, a battery shooting right under the piano: it was perfect.

The occasion of the performance of Cage’s work was the exhibition, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957, curated by Helen Molesworth with Ruth Erickson, at the ICA/Boston: a multi-faceted, interdisciplinary, many-years-in-the-making, pedagogical exhibition about a radical pedagogical endeavor. Or let’s put a looser frame around it: an exhibit that allows us as viewers to touch something of the utopian vision, the inspiration and the conditions that allowed for this confluence of makers and thinkers, and for the very inception of artworks and ideas that continue to influence most of what we term “contemporary” even now. Perhaps it goes without saying that it’s also a chance to experience some great art.

In the exhibition catalogue — which is a form of exhibition in itself, a gorgeous weighty tome of imagery and exquisite writing reflecting tireless hours of research — Molesworth looks toward historian Ernst Bloch’s notion of ‘conditions’ to “complicate our too-easy historical model of cause and effect,” suggesting “that cause and effect are not purely teleological but rather reciprocal, effecting and causing one another in turn.”1 Bloch, she notes “offers the idea of conditions, which ‘set the possible but they do not do anything.'”2 Thus, an available Christian summer camp in North Carolina; the devastation of world war; refugees, immigrés, and artists coming to America from Europe, Asia and Mexico; the Bauhaus school closing in Germany to avoid accepting Nazi teachers; the frugality demanded by the Great Depression; a classics professor fired from his tenured position; a financial gift; and the GI Bill all contributed to the conditions that fed Black Mountain College.

The school’s founder, John Rice, conceived of Black Mountain College not as an art school but as a liberal arts school that situated artistic practice at its center. Founded with an eye towards philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey’s ideas that focused on democracy and the experience of “learning by doing,” the college became a grand experiment for these ideas and many more involving intentional community and creative practice. It received its initial faculty with the arrival of renowned teachers Josef and Anni Albers from the Staatliches Bauhaus. And it was these and other individuals who took the “leap” and created a community that reflected a true cosmopolitanism, a community of diverse thinkers and makers from all over the world. They created the whole dialogic, messily democratic, educational experience that became a true crucible for creative ideas in the 20th century.

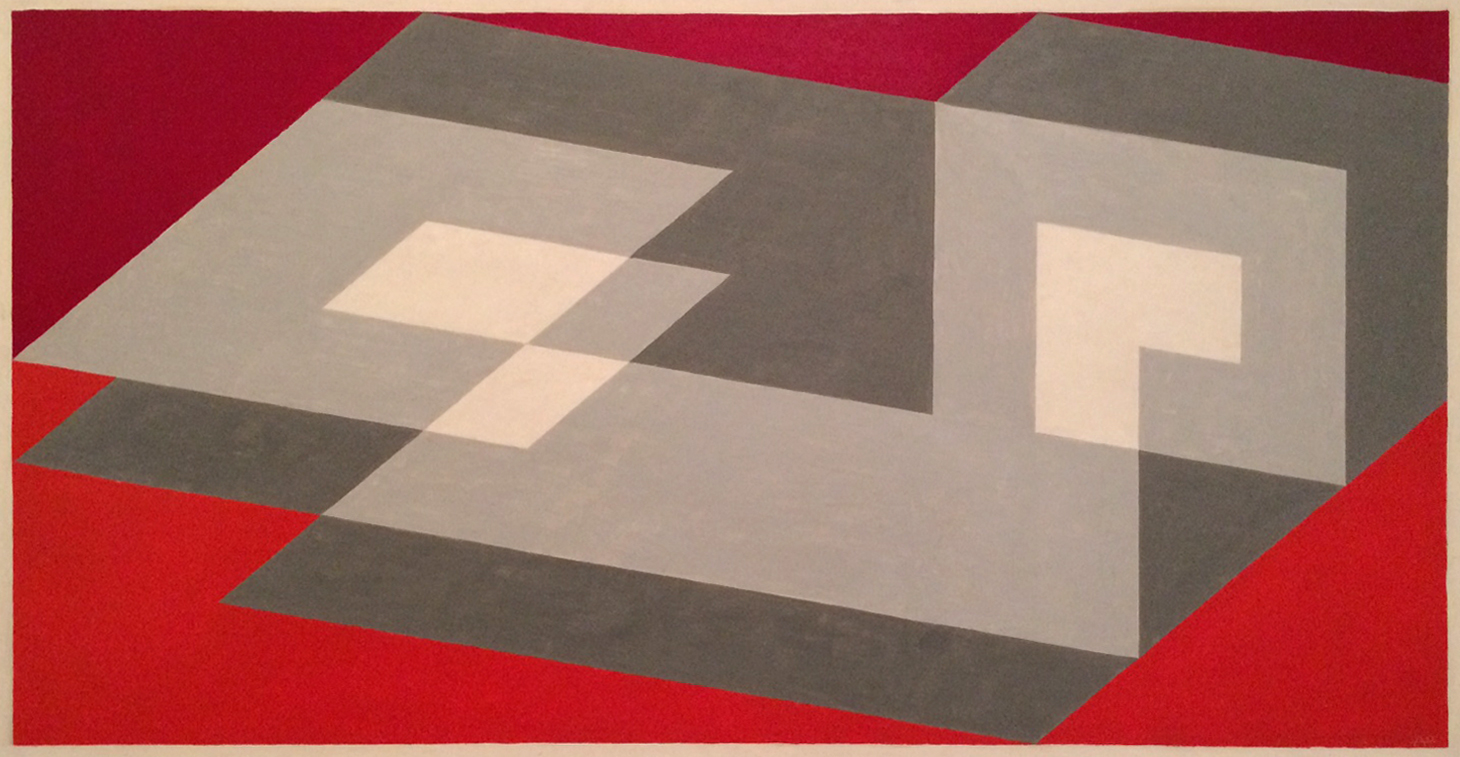

The exhibition encompasses a diversity of media and forms: while regarding the weavings of Anni Albers and the paintings of Josef Albers, you may also be listening to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 32 or Eric Satie’s The Ruse of the Medusa. While regarding the ceramics of Shoji Hamada, Karen Karnes, and Peter Voulkos, you will overhear Charles Olson reading poetry, or learn about his groundbreaking essay “Projective Verse” and how MC Richards connected his idea of breath in poetry to that of making pots. There are looms and furniture and turned wood bowls and a wall of student color studies. The ICA has planned an extensive calendar of performances and readings to accompany the exhibition; in addition to Cage’s work, there will be performances by Silas Reiner of Merce Cunningham’s Changeling last performed in Tokyo in 1964, a “reimagined” performance of the first Happening, Theater Piece No.1, and readings of ekphrastic poetry inspired by work in the exhibition. It all could be a bit much: but somehow it’s not.

The mural sized photographs of daily life at BMC made into wallpaper but blocked by heavy red-oak display cases containing weaving experiments, jewelry from wine bottle corks, and catalogues advertising the college, seem to detract from the viewing of either. But it gives substance to the myth of Black Mountain College to see students heading toward the barn with shovels in hand, digging a ditch, loaded into the back of a wood-sided lorry, and lounging by Lake Eden. You get a sense of the camaraderie and the collective enterprise as well as the utter collision — Molesworth notes collage, the kunstwollen of the 20th century — of ideas.

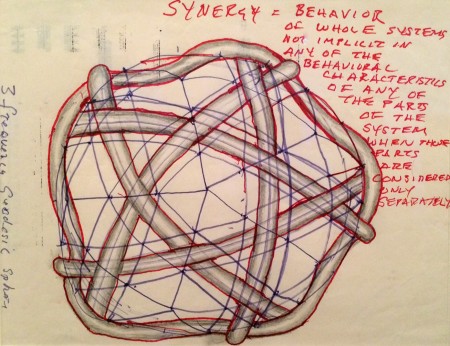

Photos of R. Buckminster Fuller’s first attempts at geodesic structures with the Supine Dome — Elaine deKooning and other students holding up the sagging venetian blind slats — are exhibited next to his early Great Circle Sphere Model. The ring he made for Ruth Asawa’s wedding not far from her early contour drawings of hands. Asawa’s Untitled Sculpture Drawing from 1951–53 and one of her suspended copper and iron wire sculptures (Untitled, 1955) — made after learning techniques from basket weavers in Mexico on a trip with the Albers — are both on exhibit. Leaf studies from Josef Albers’ material studies class connect to the weaving experiments in Anni Albers’ classes. There is a section of the exhibition devoted to the presence of the haptic in the work, the “extra-optical” in contrast to Clement Greenberg’s optical imagination. It’s all here.

An exquisite passage of paintings phrasing a succinct continuum from European Modernism to developing Abstract Expressionism exposes, as the wall text notes, “powerful continuities between the former’s commitment to rigorous abstraction and its faith in the power of art to countermand the horrors of war with the latter’s exploration of art’s formal properties and its deep meditation on the relationship between artistic process and individuality.”3 All made in 1948, moving from left to right, one moves from Jean Varda to Elaine de Kooning to Willem de Kooning, Pat Passlof, Ray Spillenger and Willem de Kooning again. The relationships between and within the works, seen all together, are entirely compelling.

[LEAP BEFORE YOU LOOK is] an exhibit that allows us as viewers to touch something of the utopian vision, the inspiration and the conditions that allowed for this confluence of makers and thinkers, and for the very inception of artworks and ideas that continue to influence most of what we term “contemporary” even now.

As well, there is the social realism of Jacob Lawrence and Ben Shahn. Cy Twombly was at Black Mountain, as was Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline and Gwedonlyn Knight. Their works are in the galleries. Photographs by Hazel Larsen Archer and Kenneth Noland are exhibited throughout the space. Jean Charlot came to Black Mountain, as did Carlos Mérida; so did Denise Levertov and Robert Creeley. Throughout the exhibition one gets a sense of this multitude of voices moving through the college, and of the community as a place of competing and diverse ideas. This diversity — this cosmopolitanism — proved to be deeply rich and productive for new creative investigations.

But in the end, the school couldn’t be sustained. The conditions changed; they ran out of funding, there was infighting, and perhaps the political climate called for something else. The participants, faculty, students and visitors moved on and disseminated ideas developed at Black Mountain College throughout new communities, an atomization mapped by the college’s last director, Charles Olson in 1956, but realized more informally after the closing of the school in 1957. You can see Olson’s diagrams at the ICA too.

The pianist, Rombola, explained to us the “preparations” listed in Cage’s scores: according to his hand-drawn diagram, erasers and screws were placed at varying positions along the strings, inside the piano. The instructions were loose enough that she could finesse the location of the foreign objects to her particular liking. And she began to play. Still radical, even these seventy years later, the piano became more clearly the instrument of percussion that it is, and our ears were pushed to attune themselves to this new form of sound, its new sense of timing and atonal qualities. Twenty minutes in, listening to that propulsive rhythmic composition, I drifted in the galleries taking in the collage of objects again; the paintings, ceramics, textiles, broadsides, photographs, jewelry, furniture and photographs, and I imagined it as it was then, in 1946: a community listening to itself as it made over the world.

LEAP BEFORE YOU LOOK: Black Mountain College 1933–1957 continues through January 24, 2016.

ICA Boston

100 Northern Avenue, Boston, MA | 617.478.3100

Open Tuesday, Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday 10am–5pm, Thursday and Friday 10am–9pm. General admissions: $15; seniors: $13, students: $10, ICA members and youth under 17 are free.

Julie Poitras Santos is a visual artist based in Portland, Maine. Also a writer, her research interests include the relationship between site, story and mobility, and often involve areas where art and language intersect. She works as Director of Exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art.