by Clare Tyrrell-Morin

Beijing-based Robin Peckham sits in the ranks of some of the most important young editors and curators of Chinese contemporary art. He’s also a Mainer. In this interview, he discusses his Maine roots, his journey to Beijing’s 798 arts district as a high school student—and his reflections on Chinese art right now.

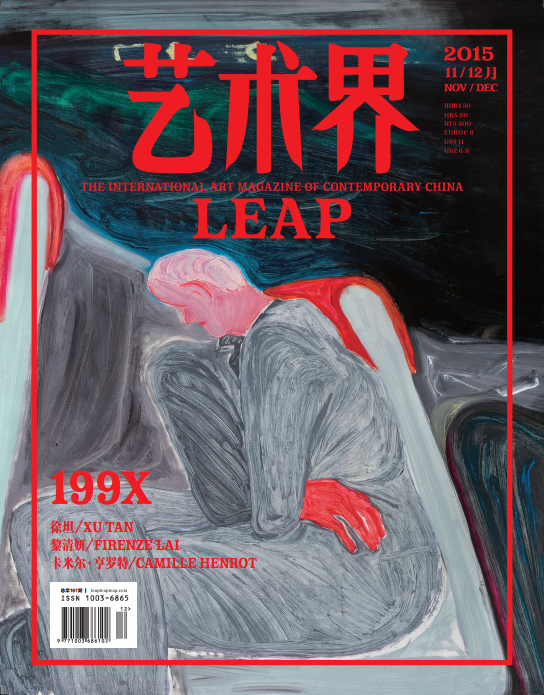

Clare Tyrrell-Morin: You are the editor-in-chief of LEAP, a highly acclaimed bilingual arts magazine from China. But you are also a Mainer. Can you start by telling us about your Maine roots? Where were you born?

Robin Peckham: I was born in Damariscotta. At the time my parents ran a bed and breakfast, the Albonegon Inn, in Southport, in the Boothbay Harbor area. I spent most of my childhood in the area and then, as much as I hate to admit it, gradually became a summer person as I grew up, keeping up a family tradition of messing about in boats. Before I got serious about art my main passion was sailing—in fact the only jobs I’ve held outside of the Chinese art scene have involved coaching youth sailing and navigating tourists around the harbor. It could have been a very different life!

CTM: You studied Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. How did your journey to China begin? What led you there?

RP: My first exposure to China was actually as a junior in high school, when I studied in Beijing for a year abroad. The decision to go wasn’t based on any particular interest in Chinese culture or even understanding of what I was getting into, but the experience was formative and incredibly addictive.

I spent the first year living with a local host family and working on my Chinese, and managed to jump headfirst into an art scene that was just taking off. A few of the galleries were happy to have me around learning the ropes and helping out with translation work. A few days a week I would finish school in the city center, take a series of bus routes out to 798—which was much smaller and quieter then—and bug dealers and curators in my school uniform. Since then I’ve never managed to stay away from Beijing for more than a few months at a time.

CTM: When you first arrived in China, what struck you the most about the arts and cultural scene you found there—in comparison to the US?

RP: My career has really been exclusively in China. Before I studied in Beijing and fell into the 798 scene I had no interest in or knowledge of contemporary art. In some ways this means I’ve had to learn about global art from a Chinese perspective rather than from an American one. As a curator and editor I think this serves me well, because my understanding of art history and contemporary culture are fundamentally comparative and, somehow, cosmopolitan. Being American, the galleries and organizations I’ve worked for have often sent me run their events in the US, so I’ve also learned about how the American art world works from a Chinese point of view.

CTM: While in Beijing, you became the director of Boers-Li Gallery. The gallery was co-founded by Pi Li, one of the most important critics and curators in China today. How was your time there? How did it shape your outlook on China’s arts scene?

RP: As a young person just figuring out what I wanted to do the art world I had the extreme good fortune to land internships with three incredibly brilliant people: Lu Jie at Long March Space, where I spent time in high school, and Pi Li and Waling Boers at Boers-Li Gallery, where I ended up when I left university. With Lu Jie I learned a lot about building long-term projects through sustained relationships with artists, with Pi Li I got my introduction to the Chinese art world, and with Waling I learned about spatial sense, presentation, and writing. It says a lot about the transformations of the Chinese art system that all three were curators who ultimately opened galleries (though Pi Li has since returned to exhibition-making at M+ in Hong Kong), and this has colored my understanding of the relationships between different kinds of organizations.

In the Chinese art ecology the gallery plays a really fundamental role, in some senses taking on the responsibilities of alternative spaces, museums, and publishing houses, and my time with Boers-Li in particular allowed me to figure out what productive, creative relationships with artists can look like.

CTM: Then you made your way to Hong Kong in 2008—the year I left Hong Kong, so our paths just missed each other. You launched the Society for Experimental Cultural Production: “a curatorial office and production team that organizes exhibitions through the exploration of connections between experimental artists musicians, curators, and critics across greater China”. Then in 2012, you opened the gallery Saamlung a cutting-edge space, which you ran for two years. How would you describe the Hong Kong arts scene to those not familiar with the city?

RP: After meeting my Hong Kong-born wife in Beijing, we moved to Hong Kong in 2009 and went a little crazy setting up different labels: there was Kunsthalle Kowloon, a name we used for projects we did out of a friend’s space in Prince Edward, and the Society for Experimental Cultural Production, which we used to apply for government grants—both of these “organizations” Venus and I worked on together, but not the gallery—and later Saamlung, which was a project space on a commercial model. We left Beijing when there was a massive crash in energy levels after the end of the Olympic boom, and in Hong Kong we found a very young, open scene where we felt we could contribute more.

Hong Kong’s art scene is microscopic but growing quickly, with help from Art Basel and institutions like M+ and Asia Art Archive; some of the most interesting artists and collectors in Asia are from or based there. I thought it was a shame how little attention many of these artists were receiving, so Saamlung was an attempt to rectify that, a way of doing exhibitions at a high standard that would put brilliant Hong Kong artists like Adrian Wong and Nadim Abbas on the same stage as Chinese and western artists like Jon Rafman and Jiang Zhi. Once we had done that conceptual work it made sense to let more professional galleries pick up where we left off. I’m extremely proud of how well all of these artists are doing now. They’ve really made something out of Hong Kong art.

CTM: Where are you physically based these days?

RP: Mostly Beijing. My wife Venus is the creative director of OCAT in Shenzhen, so she spends around half of her time there, and I work out of our Shanghai office every other week, so Beijing is our family home base. We live just across the street from 798, and spend a lot of our time in Beijing in the artist studio complexes in the neighborhood.

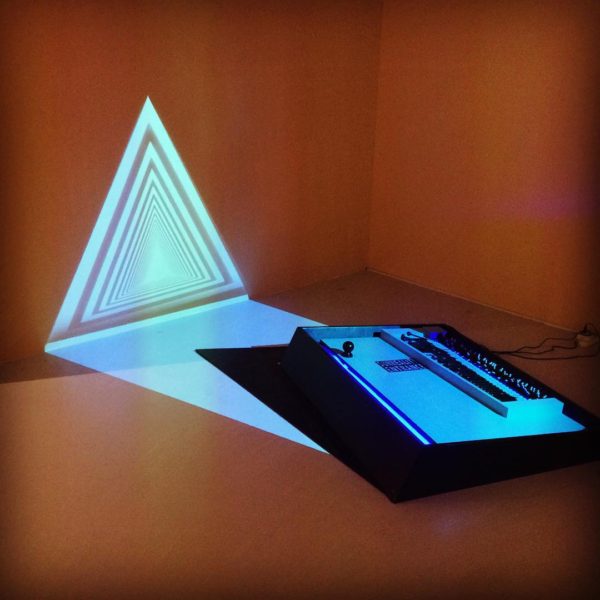

CTM: I’d like to ask you about “Art Post-Internet,” the large-scale survey of “post-internet art” that you co-curated with Karen Archey at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. What was the show setting out to explore? What were some of your questions and conclusions?

RP: For me, there was a certain generational commitment in needing to figure out why so many artists of my generation were working with the concepts and materials of post-internet art, which we define as contemporary art made with a conscious awareness of the network its influence over the production and consumption of images and objects—a definition so broad that it encompasses just about everything out there right now! We did it in Beijing for a few reasons. It seemed interesting to create some distance from the young art scenes in New York, Berlin, London, to step back and look at it from a new perspective, and I was very curious about how the supposedly frictionless space of online culture would translate.

Ultimately, Karen and I wanted to research a historical lineage for post-internet art, and to ensure that its conceptual grounding would be remembered even after some of its more faddish elements have disappeared. This project is still quite urgent in my mind. Many exhibitions now pick up on the ideas of the post-internet moment in a brilliant way, like Nicolas Bourriaud’s Taipei Biennial, but it’s also important to contextualize where these ideas come from and why they are so appealing now.

CTM: You are curating a very interesting exhibition right now in Shanghai. Media – Dali (5 November 2015 – 15 February 2016) is organized by Hong Kong’s K11 Art Foundation and the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, and includes 240 original works by Dali as well as two surveys of Chinese artists and the effects surrealism had on their works in the 1990s as well as the emerging scene. Can you explain how you came to be involved in the project?

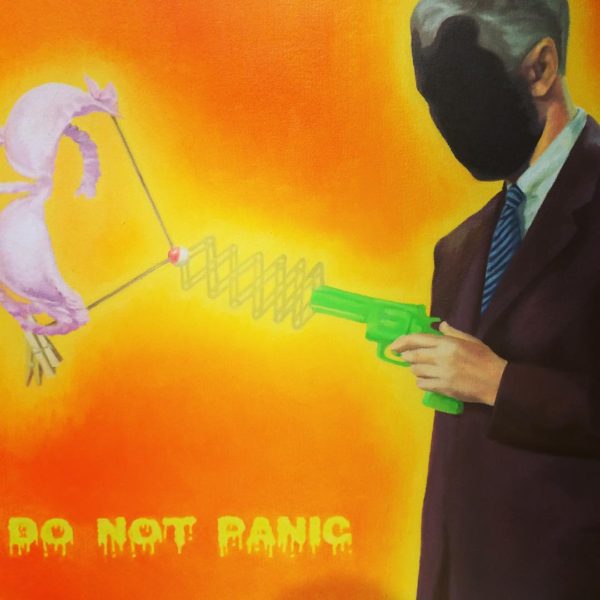

RP: I curated two exhibitions of Chinese contemporary art responding, somewhat obliquely, to K11’s Salvador Dali exhibition proper. One, The Shanghai Gesture, uses the surrealists’ idea of an “irrational enlargement” to trace aspects of surreal humor in the work of some of the more senior painters on the Shanghai scene. The other, Our Real, Your Surreal, looks at younger artists’ relationship to reality and virtual space.

Adrian Cheng, founder of the K11 Art Foundation, is a great collector and patron, and we see eye to eye on a lot of young art—he’s commissioned amazing projects just in the past year from Cheng Ran, Zhang Ding, and Chen Tianzhuo, all of whom I work with often. We had a conversation on what young people might find interesting about Dali in Shanghai today, and together came up with the idea of using art about the everyday to establish a link with Dali, who can otherwise seem like a distant historical master. I hope these two projects help bring the work to life for audiences of our generation.

CTM: There is a wonderful quote from you in the event press release: “Youth culture in China walks a line between indulgent fantasy and a rough and ready dedication to reality, a fracture that is reflected in the current culture from popular film and independent music to contemporary art. Unlike the now-established artists of the generation just above them, these young players do not dwell on the fact that China’s urban reality is at times surreal; instead, they intervene directly in the surreal as a plastic and symbolic space.” Could you give us one or two examples of young artists doing this?

RP: More established artists with whom most Americans will be familiar, like Cao Fei, who is doing the next BMW art car, were struck by how quickly their social environment was changing, and reflected that in their work: urbanization, consumerism, personal technologies all appear as a terrain of the absurd. For the artists in the generation I’m talking about in this exhibition, born in the 1980s, social change hasn’t been so overwhelming. They’ve grown up with the accelerationist hypercapitalism of Shanghai and Beijing, living in a media environment (including digital media and print media, which is not losing its influence in China as quickly as in the west, in addition to advertising and all of that) as much as a physical environment. It’s all one big soup.

Lu Yang is a great example of this. She makes videos, animations, and manga, and then allows them to circulate in this media landscape. Her superhero Uterusman is not a criticism or reflection of media ecology; it operates as and in that system. For me, Zhang Ding is doing the same thing with his music projects. At ICA in London last month he staged a “battle of the bands” in which dueling sound systems divide the audience in an architectural structure of mirrors.

CTM: In your role as editor-in-chief at LEAP, you have a unique insight into the Chinese arts scene. I wonder if you could talk about one discussion you’ve been having lately with your contemporaries, in terms of the Chinese arts scene and its direction. What are you interested in right now?

RP: I’ve been having a lot of conversations with international curators visiting Chinese artists recently, around the Dali exhibition and the Hugo Boss Asia Art Prize jury deliberations, and I’m becoming concerned that art from China is becoming less interesting for them. With many younger artists less concerned with the state or even identity politics, it’s harder now for these artists to fit into the institutional narratives. This means they’re losing opportunities for exposure, which becomes a vicious cycle with regard to their visibility on the international stage. Writing on artists helps to rectify this situation, but I think something more is needed now.

Younger Chinese artists need more chances to work on experimental work outside of the gallery system. It’s trite to complain about the lack of flexible programs like PS1, the Kitchen, Artist’s Space, Performa, or even Portland’s ICA and SPACE Gallery in the major Chinese cities, and the support structures for these kinds of things aren’t really in place here, but soon we need to find ways to help make the projects that would find a home in these mid-scale institutions possible.

CTM: Do you ever come back to Maine?

RP: Unbelievably, this past summer was my first time in Maine in eight years. It was also my daughter’s first trip to the United States. We stocked up on Dahlov Ipcar kids’ books, so her English vocabulary is mostly limited to “deer,” “lobster,” “ouch trees (pine trees),” “clams,” “loon,” “boats,” “moose.” Could be worse! My dream is to end up back in Maine someday. I haven’t managed to connect too much with the art scene yet, but I’ve just started a writing a project on the reception and misinterpretation of Wyeth’s Christina’s World by Chinese artists in the 1980s, and I hope this leads me to some research where I’ll be able to draw more connections between China and Maine.

Clare Tyrrell-Morin is a writer and editor with a focus on cross-cultural shifts and cultural hybridity. She wrote three chapters in the recently published book, Creating Across Cultures: Women in the Arts from China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, described by David Henry Hwang as “essential reading for anyone interested in the state of the arts, politics, and female empowerment.”