by Erin Colleen Johnson

In Empiricism and Subjectivity, Deleuze states, in his reading of David Hume’s philosophy, that the institution “adds many other motives to interest — motives that are often contradictory (prodigality, ignorance, heredity, custom, habit, or ‘spirit of greed and endeavor, of luxury and abundance’).”1 These divergent, and at times irreconcilable, drives are often the subject of Jessica Hankey’s photographic and video work on non-profits, community centers, clubs, and museums, as well as the relationships that constitute them. Using documentary and narrative filmmaking strategies, she investigates the unstable relationship between location, image, and perception. The specificity and universality of her images — the way the chairs are stacked at the Women’s Club or how the motivational posters hang in the community center’s halls — mirror our everyday experiences. However, through her eye for melodrama in the mundane, we are invited to reflect on and relate to, in an entirely new way, the relief and psychic toll institutions generate. Jessica’s pieces, like herself, are excellent conversationalists: rigorous, nimble, generous — always ready with one more thoughtful question, one more observation to share.

Erin Colleen Johnson: You’ve been making work about a Women’s Club in Los Angeles for years. Can you talk about what interested you about that site in the first place?

Jessica Hankey: I was drawn to the women’s club after I was displaced by a sudden cross-country move and I was pretty isolated and looking for an opportunity to connect. I was honestly feeling lost and here was this amazing building and women’s organization that had, really against all odds, survived for over a hundred years a few blocks from my house in Los Angeles. Their membership was aging and they realized that in order to survive they would need to appeal to younger members. So they were kind of seeking to redefine their purpose and imagine how they might fulfill their potential as an organization and I just completely identified with this quest.

ECJ: And they just invited you in?

JH: Yeah, I called them up and spoke to an enthusiastic person who told me I had a young-sounding voice and would I be interested in organizing programming for younger women? I didn’t have a studio and I pretty immediately proposed to them a weekly open studio group where people could just come and work. Within a few months I had joined the Board and become deeply absorbed by the internal workings and potential future of the club.

ECJ: When you started the weekly art group, were you already planning to make artwork about the club?

JH: That’s funny. I may have thought at the time that the art group was a kind of art project. I think I decided not to differentiate between community service, event planning and art. Even being on the Board, it was all one big stew. Now, in terms of representing the club — its building, history, people — in a medium like photography, I think that started with a decision to make a yearbook celebrating the centennial of the club’s building in 2014.

ECJ: What is the building like?

JH: The clubhouse sits on a main street a few blocks from the ocean, squeezed between an upscale franchise restaurant and a parking structure and somehow it just disappears. It’s painted a kind of battleship gray that is apparently its original color and people would come into the club all of the time saying, “I’ve lived in the neighborhood for 20 years and I, I just never saw you here. I never saw the building.” There’s a member of the club, Marjorie, who often talks about how she feels that people, and especially women, become invisible as they age. She tells a story about a young woman on the bus shoving her hand squarely into Marjorie’s chest and then gasping, “Oh, but I didn’t see you.” So I was thinking about parallels between the building and the women inside of it.

Behind that gray facade is a two-story auditorium with a stage and dressing rooms. The weekly studio group would meet in the club’s cavernous auditorium and gather, almost huddling, to one wall of windows to be close to the natural light. It struck me that there was something almost embarrassingly vulnerable space about our misuse of that space.

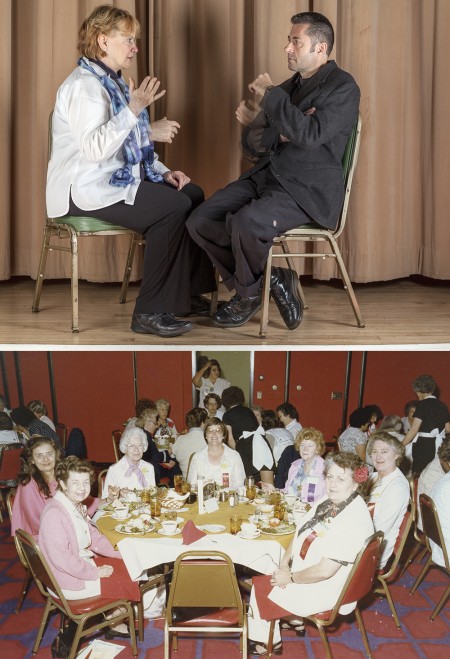

ECJ: In the 2015 multi-channel video Women’s Club (act II), much of the action takes place on the Club’s stage, how does the stage function? What role does it have?

JH: I first began to wonder why the women who founded the club devoted the vast majority of the building’s space to a stage and seating area when we (the club) were planning a celebration of the centennial of women’s voting rights in 2011. Women in California got the right to vote in 1911, nine years before the 19th amendment gave women the right to vote nationally. In planning the event, I started reading through the club’s minutes that date back to 1905 and looking through scrapbooks and what struck me was that women were using the stage to perform alternative identities and gain public speaking experience. They were in a kind of training to be more visible in society — to expand their roles as wives and mothers — and the club and its stage were a space of personal transformation.

My impetus for making Women’s Club (act II) was that I wanted to see the women of the club on that stage.

ECJ: Your photographs of the Women’s Club live in two ways. In one piece, the photos exist in a kind of yearbook with posed photos of each of the members of the club on white backgrounds interspersed with images of the building.

JH: That yearbook project was never finished and it’s still on a back burner, it’s more a question of finding funding than lack of personal interest. I love the tangibility and portability of photography in books, the way it can feel like holding a world in your hands. Photobooks have their own unique history, and I’m particularly interested in the way that photobooks have often valued the collective meaning of images over the individual meaning of a single image.

ECJ: In Women’s Club (4th VP), archival images and photographs you’ve taken of the club are framed and inhabit a wall together. In both the book and the framed images there is a sprawling constellation that allow for relationships to be made between disparate images. Is that a phenomenon that could be applied to your work in general?

JH: Well, I’m interested in what happens when images collide and in the space between the images. How do we invent connections between images to fill the gaps? I think that’s one of the things that draws me to video. That, and the desire to hear images speak.

The project Women’s Club (I.S.&I.K) was a return to video after a long hiatus. You’ll remember, of course, from our time in graduate school together that I was showing the portraits I shot for the yearbook and became interested in the process of watching viewers project histories and feelings onto the club’s members through these still photographs. I wanted to explore that space of projection. It’s significant that we were in graduate school because you get to hear a lot from people about what they see in your work.

ECJ: Tell me about your recent body of work. Are you making photographs?

JH: I’m working on a video project called Community Center that I started while working as an administrator at a social service organization. Still photography has been a part of my process for developing the project but I think it’s more a part of the research, a tool for looking and observing. I’m still shooting so it’s a little early to tell.

Community Center is an experiment. Like some of the women’s club videos, it makes use of strategies of fiction and documentary filmmaking. In this case, I’m planning to work with three or four channels that can be viewed separately, so there is a fair amount of editing that is done by the viewer herself- both in terms of sequencing and how much she decides to watch. Its vision, both through the editing and framing of shots, is tightly compressed. There’s an immediacy and a remove from the “real world” of the community center.

ECJ: How does this video relate to the many kinds of failure that your work touches on — the failure of the institution to grow and change, the failure of the worker within the community center?

JH: I think it’s tricky when we talk about failure because it implies that there are criteria of success that haven’t been attained. Now, that’s very useful when we’re talking about specific desirable outcomes, like did she pass her exam or how many deaths were prevented, for example. But my work doesn’t really establish criteria for success and in the same way I don’t think it’s really concerned with failure. On the other hand, I hope Community Center explores some of the nuances of work and institutional culture in a way that complicates notions of personal or professional success.

ECJ: In Women’s Club, you seem to be thinking about an institution like that as a mirror for the individuals who comprise it. In the community center work, it is more about how institutions either lead to or are created by dysfunctional interpersonal relationships. Can you talk about the differences you see in these investigations?

JH: Well, in my own experience interpersonal relationships can often include a certain amount of friction, miscommunication, or fear. A workplace, if you interact with your coworkers on an ongoing basis, is no different. It contains most of the personal stuff that lies outside of the workplace. The stuff that we associate with being alive. A lot of us live at our jobs, or spend a significant portion of our lives at work. In the Community Center project I’m interested in the apparent rules of a type of workplace, its official values, and how they interact with the social dimensions of the organization.

These dynamics were all present for me in my experience at the women’s club — I was on their Board of Directors for a couple of years, so I guess it goes without saying — and I think that can be seen in some of the work. But my projects with and about the women’s club grew out of being a club member and the club is more a site of production for lots of different stuff, including workshops and public talks, rather than a specific project to represent it. Some of the photos and video are concerned with the club’s search for identity. Its effort to figure out what its value is to women or the community in the 21st century.

ECJ: You tend to make work that investigates spaces that you are a part of — what kinds of effects does that have on the work?

JH: Right now, it makes sense to me to explore material that is already very present in my life. Sometimes people have asked me, how did you get that kind of access? For example, with the women’s club project. And the answer is that I had the access because it’s part of my life. I was a member of the club and began making art about the thing I was most obsessed with at that time. Something that was keeping me up at night and filling my mind with questions. And the more structured projects, like the videos, were a form of processing that experience and entertaining some of those questions.

A number of my projects use the physical reality of a building as a point of entry for thinking about what goes on with the people inside — this is true for Women’s Club and Community Center. In some cases, it’s partly a way of gaining some distance, or order, in relationship to something that is very close and difficult to reflect on. I have a couple of projects in development that kind of diverge from this strategy but are still forms of engaging material that feels very close. In some ways, they’re more personal. On the other hand, I would love work on a project that takes me to a new place or brings me into new relationships and circumstances!

A pop-up exhibition of Jessica Hankey’s work will be on display at the Bowdoin College gallery in Edwards Center for Art and Dance from April 21–23, 2016. The opening will be from 4–6pm in the gallery and the artist talk will be from 6–7pm in the Digital Media Lab on Thursday, April 21st.

Hankey’s work has been shown nationally and internationally, including recent exhibitions at HERE in New York, NY and CTRL+SHFT in Oakland, CA. She received an MFA from UC Berkeley in 2014 and was a resident at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2015.

- Deleuze, Gilles. Empiricism and Subjectivity: An Essay on Hume’s Theory of Human Nature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. Print. Page 45. ↩

Erin Johnson is an artist and curator based in Portland, Maine. She is currently a Visiting Artist in Digital Media at Bowdoin College and received an MFA and Certificate in New Media from UC Berkeley in 2013.