by Clare Tyrrell-Morin

When I first looked at Sarah Baldwin’s ink works — in a Portland teahouse in the depths of winter — it felt like I had momentarily returned to Hong Kong, staring at the cosmic creations of ink painters like Wucius Wong. Baldwin is a Biddeford-based artist whose abstract works carry undercurrents of nature, impermanence, storytelling, and hyperreality. This week, she is opening an ambitious multimedia exhibition she curated, called Influx, in the former textile mills in Biddeford. After the opening on Friday, September 15th, the public will be invited to watch the work evolve over the two weeks of the exhibition in various public spaces around the mills. She’ll be cooking ink from local materials like dandelions, blueberries, and seaweed; sewing unfinished edges of fabric; and stamping and heat-stamping ink by ironing onto the fabric. “It’s all very much rooted in what we traditionally consider women’s work,” she explains.

In anticipation of Baldwin’s new installation, I set out to her studio in the basement at Engine, an arts space in downtown Biddeford, to ask her to trace the chronology of her artistic path — and how she began to work with ink.

A path of healing

Sarah tells me that in 2011 her city life in Portland was fast becoming exhausting. She was completing her BFA at the University of Southern Maine, working in the finance department of the Portland Museum of Art, and sustaining her own artistic practice when she developed a shoulder injury. Her practice of drawing became infinitely harder and more painful. “My mind was in chaos,” she says. “I was massively stressed out.” One day, she packed up her Portland apartment and moved an hour south to Wells. She found an apartment close to the estuaries of Drake’s Island Beach and got an internship at Corey Daniels Gallery to finish her degree, where she was deeply influenced by Daniels’ brilliance, his collective works, and the world-class artists he represents.

Nature also began to appear as a major influence in her work, in particular the estuary in the Wells Reserve at Laudholm. “I would hang out in nature, take walks, then go back to the studio,” remembers Sarah. “I was still drawing during this time, but I was working bigger and trying different ways for my drawing to be more ergonomically correct, so it could be a positive thing in my life.” A year after this intense absorption in nature, something uncanny began to occur in the studio: the estuary itself began to appear in her works. “I made one piece that was writing, but it was completely illegible. As I was turning the canvas one day, I looked at it and realized that it looked like the estuary. And I thought, oh, the things that I’m seeing in my life, the visuals I’m getting, are coming out into my work. And at that point, I stopped trying to make work and started letting work be made.”

Diving into lakes

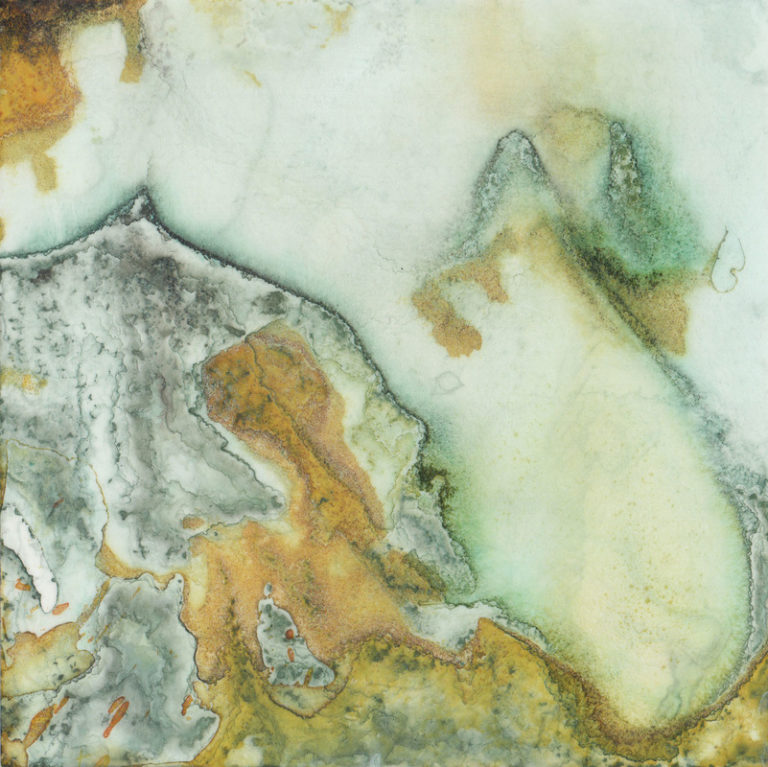

Sarah began to experiment with ink and sheets of plasticized vellum (which look like thin sheets of transparent plastic), dripping black and walnut ink down the middle. She pulls one out to show me: it’s stunning, both micro and macro at once, like a scene from outer space, from deep under the ocean, or the cells of our bodies. “The vellum means there is a dry time,” she tells me. “It sits on the surface longer, so you get more interesting marks as there is evaporation and movement happening. There is action happening without me having to have a lot of physical interaction with the work.”

In 2014, a residency at Hewnoaks Artist Colony in Lovell, Maine, brought another breakthrough. Against the stunning views of the White Mountain National Forest, she would dive into the waters of Kezar Lake and collect detritus, stones, and plant life. These she would place in tubs, throw lake water over the top as well as ink, and leave it all to soak for several days. When she went back to the tubs and pulled out the vellum to dry. “It looked like a mess, initially, but when you started to wipe it away, it revealed beautifully intricate marks that mimicked the landscape.” She had discovered a new way of drawing: one that wasn’t exhausting, but utterly freeing. “There’s a sense of not being so much in control, which is a nice practice. I set up the circumstances for drawings to happen, then I let them happen.”

seedvesselportraitb*mb

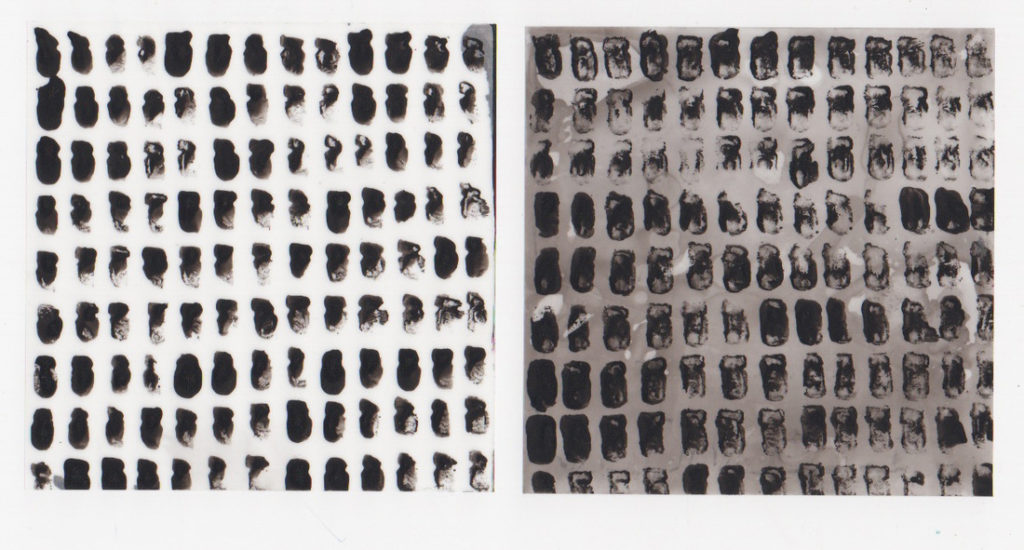

While her tubs of lake matter were forming during the days at Hewnoaks, she engaged in another meditative practice. She took the end of a pair of cheap, wooden chopsticks and turned it into a mark, hand-stamping repetitive ink marks on paper, then later on fabric and vellum. I tell her that these works strike me as utterly Buddhist. It’s like she’s capturing impermanence, constant change. She reminds me of Chinese contemporary artists like Song Dong and his performances like Writing Diary With Water, a daily practice where he uses a calligraphic brush and water to write his innermost thoughts on a stone — the diary quickly evaporating. Or his famed work, Stamping the Water (Performance in the Lhasa River, Tibet). There is a purity in her practice, a deep trust in the process itself.

“Beginning to study Buddhism, which I did a few years ago, I do now see these works as an illustration of karma,” says Sarah as we peer at her rows upon rows of stamp marks. “Each second, a state of mind is arising and making an impression, planting a seed that will then later come to fruition.” She says that she recently read a quote by John Cage on an invitation to the solo exhibition by the Maine artist Sarah Bouchard (also represented by Corey Daniels) at the Ogunquit Museum of Art:

“I want to give up the view that art is a means of self-expression for the view that art is a means of self-alteration, and what it alters is mind.”

“That rings 100% true to me,” says Sarah. She says she’s even created a name for this new sense of self that was appearing in her artistic practice. “In connecting with nature, I wanted to cultivate a better self and I had a name for it: the moniker Maud.” A play on her love of British mod fashion and her Norwegian descent, it’s the name you’ll find today when you visit her website.

Creating art in Biddeford: Influx

Today, you could say that Baldwin has left her retreat phase and reengaged with the world. She spends several days a week working in the mills of Biddeford with the renowned bookbinder Scott Mullenberg. She can also be found with the Autus Collective — a free-forming collective of local artists — and working in her own studio. For her upcoming project, Influx, she is collaborating with eight other artists for a mass takeover of inner courtyards, hallways, and rooms of the Pepperell Mill Campus. The artists include Alex Mead, Jarid del Deo, Julie K. Gray, Marques Bostic, Michael Evans, Christy Matson, Lucky Bistoury, and Ann Thompson. As their exhibition statement explains:

The collaborative of artists working to present this event seek to explore the reciprocal relationships between the mill, the river, and the city that developed around it. By utilizing part of the Riverwalk pathway, patrons will be able to explore artwork that is inspired by the past, present, and future of the mill, the natural elements of the nearby river and ocean, as well as the activities of the people in the mill and surrounding urban areas.

It occurs to me that it’s like Sarah is at Hewnoaks all over again. Except this time, the tub has been replaced by an entire mill complex, and instead of inanimate organic matter, she’s placed a bunch of humans in the space — a space with flowing water at its heart — and left them with time to manifest their own forms.

She says that organizing this exhibition is very much a process of self-alteration. “In putting together the show and being the organizer, I find myself more and more considering the reaction to putting this exhibition together as the form of art: I’m helping to facilitate an experience. And this is a very Fluxus idea of life and art — instead of ‘I need to make a painting or sculpture to be an artist’, it is, ‘I need to work with intention with whatever I’m doing.’”

That said, once the show kicks off, Sarah will be retreating to her own solitary practice for stretches of time during the two weeks. She’ll be making repetitive stamps in ink on fabric in various spaces of the mills in a large-scale continuation of her seedvesselportraitb*mb series. Like the outgoing tides of an estuary, she’ll be drawing back within herself once again — but this time, she’s inviting the public to come along and sit with her.

Influx will be on view at the Pepperell Mill Campus in Biddeford, Maine, from September 15–September 30, 2017. An opening will be held in conjunction with the Biddeford River Jam Festival on Friday, September 15 from 5–9pm. For more information, see Autus’ website.

You can see more of Sarah Baldwin’s work at her website.

Clare Tyrrell-Morin is a writer and editor with a focus on cross-cultural shifts and cultural hybridity. She wrote three chapters in the recently published book, Creating Across Cultures: Women in the Arts from China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, described by David Henry Hwang as “essential reading for anyone interested in the state of the arts, politics, and female empowerment.”