by Rose Linke

A Long Wait (ALW) is a biennial event series and platform for artistic inquiry that uses Fort Gorges — an obsolete military fort turned public space on Hog Island in Maine’s Casco Bay — as context, material, and site for performance, sound, and social practice artworks. The public is invited on boat excursions to the rarely-visited island where artists facilitate inventive and meaningful engagement with the site’s history and architecture.

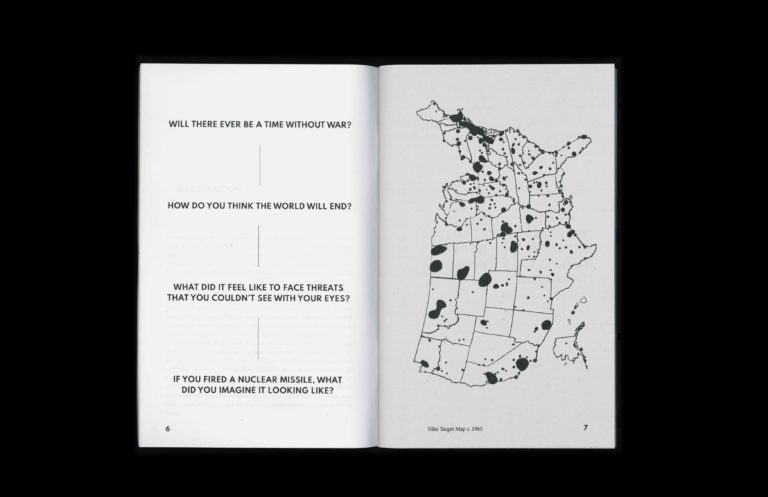

This year, participants are invited to join Bay Area artists Francois Hughes, Yulia Pinkusevich, and Andrea Steves for an interactive, multimedia experience at Fort Gorges. Inspired by the stories of veterans stationed at Nike Missile Sites during the Cold War as well as Russian veterans who served during the same period, Double Vision invites collective reflection on the history of the United States’ nuclear missile defense system as well as current nuclear threats and fears.

In the following conversation, editor Rose Linke and Double Vision artists Francois Hughes, Andrea Steves, and Yulia Pinkusevich discuss the project’s origins and influences.

Rose Linke | Double Vision began in a very specific landscape after a series of conversations with veterans formerly stationed at Nike Missile sites across the US. I’d love to hear more about the early days of the work.

Francois Hughes | We were at a residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito, California, which is surrounded by park land that was never developed because it was used by the military — before WWII, during WWII, and during the Cold War. Five minutes up the road there’s a historic Nike Missile Site. Veterans come from around the Bay Area and they basically give a tour of the site to people who want to see it once a month. It’s amazing that these people are coming back and telling their stories. All of the things they were talking about were very technical. We wanted to go beyond the technical and figure out what these folks’ lives were like on the base. What they thought. Initially, we thought it must have been really intense. Thinking about nuclear war all the time. We asked them, What were your dreams like? People didn’t remember their dreams. No sleep, no dreams. Also it had been a long time since these folks served, and of course, none of the vets knew who these crazy people were asking about dreams. Eventually we started collecting oral histories as a way to document the program, with the intention of creating an installation in the park in San Francisco that allows for reflection on the conditions of the Cold War, and how it applies to today. Later we decided to expand the scope of the project and “get the other side” of the Cold War, at which point we started interviewing Russian veterans about their experiences.

RL | The Nike Missile program provides critical context for the Cold War — and yet, many people don’t know about it.

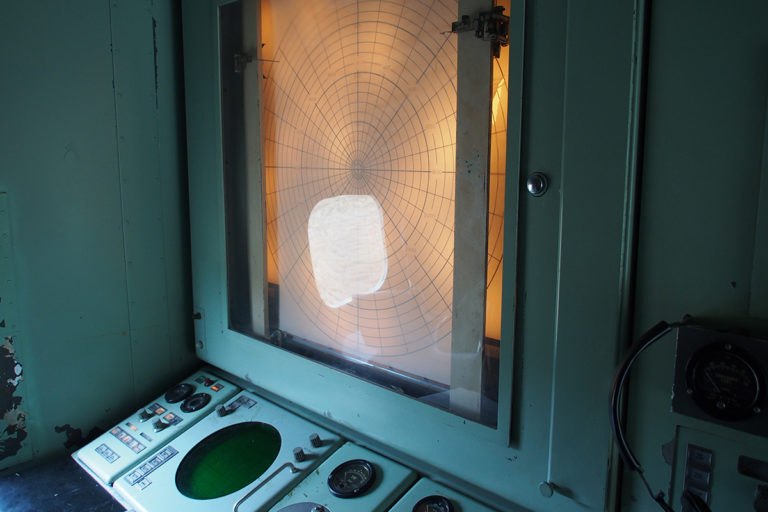

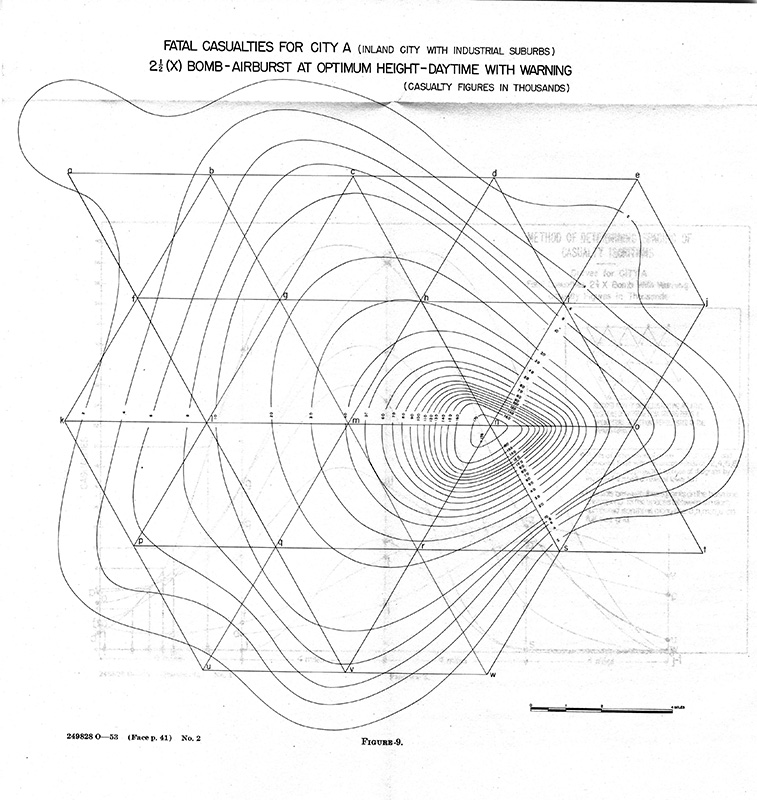

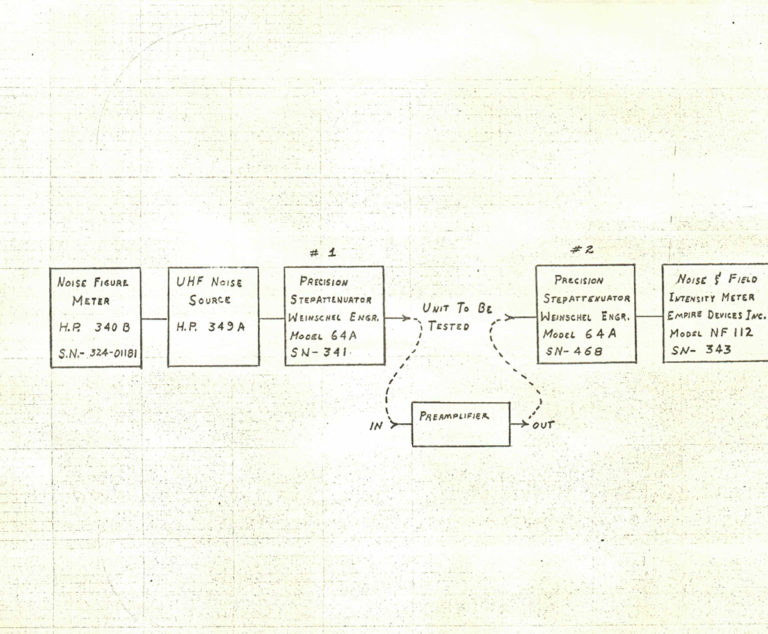

Andrea Steves | The Nike Missile program was a massive anti-aircraft defense system that was developed and proposed by Bell Labs in 1945, then built out in the early 50s. The name comes from Greek mythology and the goddess of victory. It was intended to protect the U.S. — mostly military bases and infrastructure — from incoming bombers and was massive: several hundred nearly-identical launch sites with radar tracking and missiles were built all over the United States. The system was highly sophisticated, missiles were computer-guided and could follow the target if it changed course. The sites were staffed largely with young men, many only 17–19 years old, who were drafted to sit on watch, ready to fire at any incoming bombers (“would-be aggressors” as the vets refer to them) with missiles that were armed with nuclear warheads. Imagine you’re drafted into this situation, and you find yourself on these intense shifts, waiting for the enemy. These veterans now in their seventies and eighties come back to the Headlands to talk about their experiences. A lot of what they describe is the waiting, the boredom, just attempting to pass the time. We wanted to explore this idea that you’re working these long shifts and also really needing to anticipate something happening at any moment. You have to stay awake and alert. Some of the veterans were more affected than others, but everyone talked about being exhausted. One of the veterans we spoke to described the experience of watching and waiting as 99% boredom and 1% panic. Everything was kept relatively secret: the fact that there were nuclear weapons on the base was kept secret, even within the Nike program, because everyone was on a “need-to-know” basis. So the operator of the radar trailer might know the radar trailer they were working in, but not what was happening right up the hill.

RL | On the one hand, the day-to-day experience of these veterans is so closely tied to the specific technological and political circumstances of the time. But in listening to their stories, they are also so relatable in the way the mundanity of the workplace grinds away at you.

FH | In food service there’s this word: clopeners. It means you close and open the store, staying late, coming home to catch a few hours of sleep and then getting up before dawn to open up the store, maybe you dream you are still working. I mean heck, I dream about my job when it’s stressful, and I don’t do clopeners. Capitalism takes your working life but it affects the time between working hours too. It can take your dreams. The military is a workforce. A lot of military critics think about the military as a killing machine. What we want to point out is that the military is a workplace. A workplace where the culture is drills. It takes you over for days and days. Even when they were not at work, those drills stayed with the people who did them.

AS | For many, things were boring, slow, just waiting for something to happen, waiting for the alarm to sound. Some of the interviews we conducted shared stories of Vietnam vets who came back to the base after service going crazy, and some veterans doing things on purpose to get kicked out of the base.

FH | It’s complicated though, a lot of these vets that we spoke to went into this kind of service because they didn’t want to go to Vietnam.

AS | It’s interesting to think about the different conditions of war in which human bodies are not being destroyed, but there’s this suspension of time. So much of the daily life and work in the program was anticipatory preparation and repetitive drills, and we think a lot about how these preparations are similar to the “duck and cover” drills of the era which normalize a culture of war or the idea of being under attack. These drills really cemented operations in the memory of the veterans: they have a somatic memory, they’re able to play out what happened. But it’s also interesting to hear them describe what they remember beyond the technical drills: they talk about things like the smell of the radar vans, or the food in the mess hall — mundane details.

RL | The phenomena of water, wind, and other weather are dominant at the Headlands site and quite naturally extend to the site at Fort Gorges. Is there any resonance, metaphorical or physical, with the concept of waiting for something that may or may not ever come?

FH | I think there’s a resonance with the kind of fear and powerlessness in the face of the sea or the impenetrable landscape, which you often see in paintings whose subjects are the natural sublime, such as Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), and the fear and awesomeness of the enemy whether that be the Russians or others from across the Pacific, or just the enemy of total nuclear annihilation. Mutually assured destruction. This is something we thought about but not really something we heard from the veterans.

RL | It’s interesting, because fog has been used figuratively to describe a loss of what to do since the 1600s. The etymology of the phrase fog of war is itself shrouded in a bit of uncertainty — the writer it’s attributed to never actually said it. What Carl Von Clausewitz actually wrote is this: all action takes place, so to speak, in a kind of twilight, which, like fog or moonlight, often tends to make things seem grotesque and larger than they really are.

AS | When we first developed the piece at the site in the Headlands, it was extremely foggy — at the edge of the coast you could see nothing, and sometimes could barely tell that the ocean was there. This got us thinking about threats you couldn’t see with your eyes, and the way the veterans had a view of the enemy mediated through small radar screens — they never could really “see” anything. There was a deep and constant sense of dread. Even though the fog obscures the ocean and the enemy, people knew it was there, and were afraid of it. In part this fear allowed for the justification of military spending, buildup of nuclear weapons, and the construction of the defensive missile program. We’re interested in the ways that the “enemy” was seen, understood, and countered in this history and how this concept extends to our present moment.

FH | It’s also strange to think about soldiers working on a program that could have been a part of causing nuclear winter or massive ecological destruction in such a beautiful environment.

RL | Right — it’s a landscape that’s such a fixture in the imagination of everyone who lives in the area or who has passed through. It’s a respite and a refuge. Somewhere you go to feel the awe of the land and sea meeting. And yet, the city is right there. And sometimes it’s visible from the hill and sometimes all you see is the mist of nothingness. From our point in time, it’s incongruous to imagine these hills as the front lines of defense.

Yulia Pinkusevich | The Marin Headlands has a fascinating history, the original settlers were the Miwok people who lived sustainably from the abundance of the land and sea for centuries. Ironically, the earliest western settlers were Russian. Rugged Siberian fur trappers attempted to live on and around the Farallon Islands (notorious as a breeding ground for great white sharks) and hunt anything they could catch, mostly seals, otters, seabirds and their eggs. By the time the U.S. military took over the Marin Headlands for defense, the place already had a very rich history. So despite the fact that Fort Gorges and the Marin Headlands are on opposite ends of the country and were developed for different reasons, they have a lot in common. Both are located at strategic national frontiers, both sit on the edge of an ocean in stunning natural settings.

RL | How have these themes informed your installation for A Long Wait?

AS | In our conversations with ALW curator Erin Johnson, we came to recognize that Fort Gorges’s past, coupled with its environmental precarity — tide and weather changes, crumbling infrastructure, lack of electricity — made it the perfect setting for a project that reflects on and confronts the unknown. The site was interesting to us as military infrastructure that was built but never used in a conflict. The fort was first proposed following the War of 1812, but wasn’t constructed until after the end of the American Civil War, more than fifty years later. It’s an incredible site, but its history is one of prolonged waiting and unfulfilled expectations. In a strange twist of fate, by the time it was almost complete, modern explosives had made the fort obsolete. The Nike Missile program, similarly, was constructed, replaced several times, trained on, but never needed to be used. In both places, we want to explore the incredible scale of resources poured into this military effort. So we’ve been essentially working to set our material to the site, using its unique architecture to present the audio and archival video we’ve gathered with the intent of allowing visitors to reflect on the Cold War and on the idea of waiting.

FH | Interestingly, Fort Gorges is the doppelgänger of Fort Sumter, where the initial battle of the Civil War was fought. Both Gorges and Sumter were pointed at external enemies, but it turned out that the enemy was at home in the case of Sumter. Where our project began in the Marin Headlands (on the West Coast), there was a history of military infrastructure built before the Nike site. You have Fort Barry, which was a pre World War I fort and barracks. During World War II, the army built anti-ship and anti-aircraft batteries in case of attack by the Axis powers. Then the Nike site, which was anti-air nuclear missiles for fear of Soviet bombers. If you look at Fort Gorges and the Marin Headlands you can see a whole range of the U.S.’s enemies and the discarded defenses. Old emplacements like snake skins outgrown with each enemy and new warmaking technology. It’s impossible to go a quarter mile in the Headlands and not come upon these husks, these bunkers or old sandbag nests.

AS | But there’s also the spatial resonance between the Headlands Nike site and Fort Gorges. Both sites offer a view from the “edge of the earth” — a perspective that looks out over the water from the edge of the U.S.

FH | One of the things we thought about was the way in which there were some resonances between aesthetic views of landscapes and military views. The same thing that makes a landscape beautiful or picturesque, namely, a high vantage point, very clear lines of site, also makes for an easily militarily defensible position. The lines of site in one case are to survey many things over a great expanse. The other is to see the enemy from a long way off and destroy them. It’s interesting that the logic of military views is what probably kept the Headlands undeveloped, and now it has been transitioned into being a space for seeing dramatic/expansive views of “nature.” (There’s a couple reasons for the title Double Vision, the doubling of military and aesthetic views.)

RL | There is a tension between the anticipatory nature of waiting and the reflective, retrospective act of remembering. How does this tension reveal itself in the language of the veterans or the architecture and infrastructure of these types of sites?

FH | I think the sites are about remembering different types of anticipation. Some of the veterans talk about military anticipation, they talk about the Cold War, duck and cover, fearing nuclear war, etc. What’s interesting is that type of anticipation stays constant and the idea of some enemy to fear stays constant, but the particular form of the enemy shifts depending on the economic and political situation. This is echoed in their testimonies where they express the fears of the past in metaphor by talking about the fears of the present (e.g. what they call terrorism or lone wolf attacks). The other thing is that none of the veterans thought that the Soviets would attack — the public were perhaps more worried about the Soviets than the veterans on either side Soviet or American. There’s a tension in the site in the sense that when they speak about it to the public, the story isn’t about waiting, even though that’s a lot of what it was about. It’s more focused on the specifications of the missiles, the drills, on the use of the weapons (not the time and space between).

AS | The form that our work has taken is using FM transmission and small radios to reanimate these sites. The idea is to allow visitors to explore the landscape and come across zones of signal where the veterans stories are playing through the radio. One of the reasons we chose to work with FM transmission is that the anticipation of tuning in, finding a signal, seems to reflect the way that the veterans describe observing signals. There’s a tuning in to a signal that represents an invisible threat, and there’s also a tuning in to these historical accounts almost as if ghosts of the past are sharing memories.

RL | The act of recalling and sharing memories from a distant past is such an apt analog to the idea of reaching through static to find the signal. I’m curious to hear more about working with Cold War veterans from both the U.S. and the USSR — since as a team you have roots in both the U.S. and Russia.

YP | It’s been interesting to work with both Soviet and American veterans. To my surprise neither of them regard the other as “the enemy,” both sides say that it wasn’t personal and they were simply doing their jobs. The Soviet vets we interviewed immigrated to the U.S. later on in life, so perhaps their sentiments aren’t aligned with everyone who served in the USSR. They mostly expressed respect and curiosity towards the American vets. Those who encountered Americans during their service, had favorable though somewhat envious memories to share, one guy listed all the nice things the American servicemen had on their battleships, linens with high thread counts, camel hair blankets, well-tailored suits, fancy gadgets that calculated wind and velocity at the push of a button. I feel that focused attention on these seemingly trivial goods at a time of war speaks to a general scarcity of quality products available to the Soviets at the time. The American vets didn’t mention the linens, mostly they were interested in discussing the various technologies they worked with. They also discussed the tough schedule they endured during their service, and the extreme sleep deprivation as well as the harsh irrational treatment by their higher ups. In contrast, the Soviets often talked extensively about the great quality of the food and the reasonable schedule they followed while in service. The U.S. military training seemed to focus on the idea of the enemy more so then the Soviet training.

RL | One of the Park Service rangers, Al Blank, who works at the Nike Missile Site often ends his tours asking the audience if they prefer freedom or safety. So I ask you all: What do you prefer, freedom or safety?

YP | In many ways both are an illusion, a story we sell ourselves to go on. I believe that in times of relative safety, one would prefer more freedom, but in a time of war, especially war on your soil, which is something America experienced little of, the innate desire for safety as defined in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, some freedoms would be swiftly traded (or revoked by the government) in the name of safety. History has proven this time and again.

FH | Which would you prefer, to lose your arm or your leg? I prefer neither. The problem is thinking we can’t have both. The people who pose this question want to say that we can’t have both, usually they mean “freedom” as “civil liberties.” They then counterpose this to the safety of less freedom, a curtailment of civil liberties, more money to surveillance. But less civil liberties and more surveillance don’t make us safer. Quite the opposite, they just make it harder to affect our government and its policies. The problem is the question really as it assumes that freedom and safety are opposed.

RL | In your conversations with veterans, you asked them What does it feel like to face threats you can’t see with your eyes? I’d like to turn this question around, and ask it of you.

YP | A lot of the vets discussed the immense boredom most of the time, spiked with the anxiety and anticipation of potential threats. They trained endlessly, in harsh conditions, so if an actual threat presented itself they would be ready to follow protocol without question. I believe that is why the Americans were sleep deprived — to keep soldiers in general state of fatigue so no extra energy would be left to question orders or worse.

One Soviet vet said, “It wasn’t important to lay eyes on them, it was important to understand their parameters.”

One American vet told us he had to stand guard at an outpost. He discussed the very specific way he would lean on the post in order to be propped up just right, so he could actually sleep standing up, but still look alert from a distance. I think soldiers experience much boredom waiting for this enemy.

Please join the artists at Fort Gorges on Saturday, October 13, 2018 for A Long Wait 2018. Participants are invited to engage with this historic site while listening to radio transmissions and viewing archival video. Boats depart from Chandler’s Wharf at 1:30pm.

The artists would like to thank the support from the Puffin Foundation, the Kindling Fund, SPACE Gallery, and Mills College.

The Portland-based press Orbis Editions has published an artist book in conjunction with the public art event A Long Wait: Double Vision, visit orbiseditions.com for details. Tickets for the public event A Long Wait: Double Vision, which takes place on October 13, 2018, can be purchased at http://alongwait.com.

This interview is part of an ongoing collaboration between The Chart and Orbis Editions.

Rose Linke is the editor of A Long Wait: Double Vision (Orbis Editions, 2018).

Double Vision is comprised of artists Andrea Steves, Francois Hughes, and Yulia Pinkusevich.