Alison Hildreth and Juliet Karelsen work in the language of abstraction. As artists often working in mixed media, each moves along the borders of micro and macro scales in various ways to uncover what’s at stake among urgent environmental issues. Hildreth and Karelsen’s work addresses, among many things, deep connections in Maine’s natural world and the dark way that we, as a species, have failed to protect the planet. As the daylight hours waned late this fall, the pair met in Hildreth’s long-time studio at the Bakery Studios in Portland to discuss these topics — as well as the influences that have inspired their work over the years — on the occasion of consecutive exhibitions at Speedwell Projects in Portland, Maine.

Alison Hildreth | Camus has said, “A person’s work is nothing but this long slow trek to rediscover, through the detour of art, those two or three great but simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” I think that we draw on our childhood memories. I remember as a child building landscapes of twigs and acorns and moss with paths between them; an early kind of mapping. I spent a great deal of time outdoors alone with nature as my workshop. I believe you carry that imprint. Children are able to weave the worlds of imagination and reality; I don’t know when we lose that. I find that walking is an essential activity; when I’m encountering new terrain I’m much more present than when I’m taking a path I know.

Juliet Karelsen | I grew up in New York City and my family spent some summers on Cape Cod. I would spend time in the scrub oak forest behind the house we rented there. I was so in awe — I’d never experienced “Nature” before. I knew intuitively that I was with something huge, in all the spiritual, mystical, metaphysical energy of the woods. Moving to Maine has allowed me to get in touch with all of these feelings again: I take the same walk over and over and it puts me so in touch with what’s at stake right now. If my mind is moving too quickly, I try to pause for ten minutes and stand perfectly still to get myself to be in the moment. I have been thinking a lot lately about the Denise Levertov poem, “Sojourns in the Parallel World.” She writes,

A world parallel to our own though overlapping.

We call it ‘Nature’; only reluctantly

admitting ourselves to be ‘Nature’ too.

AH | Yes, that separation seems to be more apparent all the time.

JK | You know, if I ever run into a large animal in the woods — a deer, a moose, or sometimes I try to imagine what it would be like to run into, say, a hippopotamus in the stream behind our house — it gets me in touch with the fact that I am an animal, too. That you — we — are just as much a part of a world of living organisms as anything else. And I feel like we forget that.

AH | There’s a kind of recognition, isn’t there?

JK | I just read a book called Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses by Robin Wall Kimmerer which is written through the lenses of science and self reflection. Kimmerer, who is Potawatomi, writes about moss and lichen and the spiritual side of plants. She describes a particular moss that grows on a particular type of wood — and only if a chipmunk has first gotten the spores of that particular type of moss on its feet and runs across that particular type of the log does that moss grow. Such organization and attention to detail!

AH | W.G. Sebald is one of my favorite writers. He writes in The Rings of Saturn, “The greater the distance, the clearer the view: one sees the tiniest of details with the utmost clarity. It is as if one were looking through a reversed opera glass and through a microscope at the same time. And yet…all knowledge is enveloped in darkness.” There’s a fascinating correspondence between the aerial views of things and the microscopic views. You can think of the nervous system — and the veins and the arteries as a kind of conveyance system — and then you can blow that up into highways. The tiniest things are mirrored all the time in nature — a river delta looks very much like the neural endings of brain cells. This kind of magnification of microscopic forms is something that interests me — that kind of pulling away and then zeroing in and pulling away.

JK | Yes, one can see that a lot in your work.

AH | It’s not such an original idea, but it’s the way I tend to see the world. Like a bat. I studied landscape architecture at one time — maybe that has influenced the way I see things. Even when I was a child I liked looking down on things and drew pictures like that. Reading has influenced me a lot as well — when I was young, the maps of the Hundred Acre Wood (from A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh) and Paddle-to-the-Sea by Holling Clancy Holling were so absorbing. W.G. Sebald takes walking trips that weave together landscape and history. One walks with him along the coast of Anglia and all of a sudden you’re in the Imperial Gardens with the dowager empress and her imported European train. One steps through a door into a whole other world. He does this seamlessly, I think I would like to paint this way.

JK | That’s so interesting that you’ve been influenced by a style of writing. Did that become a purposeful choice for you to follow his style in a visual way ?

AH | I really thought that’s the way I’d like to work. I’d like to be able to embed all these different ideas about geography, history, time in a continuum in a single work.

JK | People have described your work as apocalyptic and dark. How does that fit for you?

AH | I don’t think of my work as apocalyptic rather but rather an unplanned journey — the metaphorical idea of going into a dark cave to seek knowledge. The Greeks would go underground to visit the shades — not the underworld as in Christianity, of flames of hell and the arch fiend devil, but more of a place of sadness. You get the impression that these people are sad because they’re no longer living but also because they are wise, that they have lived a life but in their descension retain their memories. You see it over and over again in fairy tales and myths. Ereshkigal and Osiris make descents to gain knowledge. I think that we have perhaps made darkness into a metaphor for something fearful and that is not my view.

JK | Something like depression or the black hole or the bottomless pit?

AH | Exactly. What does darkness mean for you?

JK | One thing I think of is how this time of year can be so hard due to the long darkness from the shortening of the days. I’ve found that once I think of it as a time of incubation and wisdom, I can embrace this powerful time of quiet and darkness. When we look at one of your most recent paintings — the one people have referred to as apocalyptic — it strikes me that it also resembles the darkness of outer space. In thinking about the possibility of an apocalypse, some people say that the world will be okay: the mosses — which are extremely adaptable and resilient in darkness and atmospheric changes — and the red tailed hawks and roaches and rats — those species without special niches — will survive and start anew. It’s us who will perish.

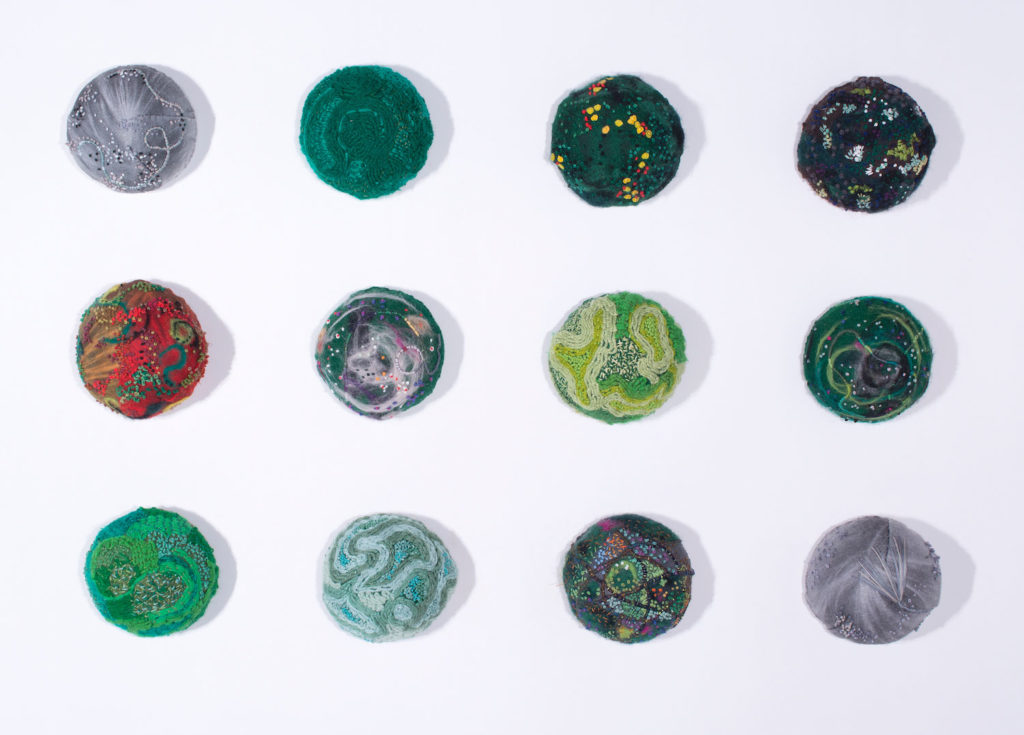

I share an interest in working with images and ideas that question scale. In my work I like to raise the question: what are we looking at when we look down at the forest ground? The lichen and moss growing in the woods, or is it out into a celestial pattern in the universe? I had a teacher at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts who, in 2016, told me, “You either make a picture or you make a field.” She meant that when one makes a picture, one is striving to create an image already in the mind. When one makes a field, one has less of an idea of where one is going or how the work will turn out. As I have shifted from painting toward working in fiber and mixed media, I realize I am now making fields. It’s been a shift from the intellect of the painting to a new connection to the deep pleasure and magic of material — honestly a feeling of ecstasy that I get when I am looking at colors and light and textures in nature. I am attempting to recreate the experience of seeing and feeling what it is to stand in the woods.

AH | Yes, I suppose what you’re talking about is a kind of surrender. When you let go of what you know. I see the unplanned journey here, too. I’m currently reading Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil deGrasse Tyson — what an absolutely amazing and comforting thing to know we are all made of particles and that we will go back to being particles. To me, when we talk about darkness, that arc of space and the black holes and the asteroids and the whole order and disorder of space — it’s the kind of darkness not of going underground, but the darkness of the world that we came from. I don’t think of my work as apocalyptic. But we do seem to be failing as a species. We haven’t figured out how to live in the world we are part of. We have the brains. We should know! I guess it is true that man’s reach outstrips his grasp.

JK | The way you say this gives the whole subject a kind of distance — as if you’re pulling away from it. It makes me think of the Greek myths and the forces of ego as well as the Buddhist ideas of how we are prone to greed, to wanting more pleasure, to seeking immediate gratification. It’s part of our nature that we have these desires but they can become demonic if we let them take over.

I started stitching and using fiber and making three-dimensional lichen work about three years ago. Suddenly so many artists who I’d been moved by came back to me: Charles Burchfield’s huge mystical watercolors that act as portals to describe the sound and movement of the woods and fields; Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms that bring me into outer space or to an infinite city or into uncharted underwater territories; Patrick Jacobs’s small landscape dioramas embedded in the walls of museums like the Museum of Art and Design in New York or the Portland Museum of Art. All of these pieces transported me — they were nothing like the paintings I used to make. But with this switch in medium, I feel a new freedom. It really feels like this is the kind of work I’ve always wanted to make. I think exploring a medium that I haven’t been trained in has brought me back to what Suzuki calls “Beginner’s Mind.” These are the conversations I’ve been wanting to have in some deep way. I feel like my focus is now on what’s at stake. That I’m talking about preserving these incredible jewels. Preservation.

AH | I think one of my biggest moments of being impacted by a work of art was seeing a William Kentridge show at the New Museum long ago when it was on Broadway. I’d never heard of him before. There was an enormous projection on the wall of refugees walking in a line made with torn pieces of black paper torn and blown up with a musician singing the most mournful song. The impact was very physical, I was struck by the sense of where an incredibly successful piece of work can take you. Mark Dion is a true naturalist and amateur scientist, and his approach is a combination of the serious researcher and artist and humorist. I think he’s addressing this whole museum idea of categories and storage and then of course because he cares deeply about nature. I saw a vast installation by Anselm Kiefer in an airplane hangar in Milan. There were seven towers made of concrete, spewing out all kinds of detritus, micro film, broken glass — it truly seemed like the ninth circle of hell. I guess the word apocalyptic would also apply. One is so aware of the materiality — it all comes together at a distance; when you come close it’s just a geography of material. His work seems sad to me — a nostalgia driven by history and mythology and German fairy tales and myths. It is as though he is trying to retrieve something irreparably lost. Finding one’s way in the forest. As we all do in some respect.

There’s another Sebald quote, in Austerlitz, that I love:

And is not human life in many parts of the earth governed to this day less by time than by the weather, and thus by an unquantifiable dimension that disregards linear regularity, does not progress constantly forward but moves in eddies, is marked by episodes of congestion and irruptions, recurs in ever-changing form, and evolves in no one knows what direction?

Isn’t that wonderful? Human life.

Alison Hildreth’s exhibition, FLIGHT, is on view at Speedwell Projects through Saturday, January 19, 2019. An exhibition of Juliet Karelsen’s work will follow, from January 25–February 9, 2019, also at Speedwell, with a reception on Saturday, January 26.

SPEEDWELL projects

630 Forest Ave, Portland, ME | 207.805.1835

Open Thursday, Friday, and Saturday 12–6pm, and by appointment.

Alison Hildreth graduated from Vassar College, studied at the Art Students League and National Academy in New York, and received her BFA from Portland School of Art. Hildreth is interested in history, cartography, literature, and the natural world and how these disciplines weave together into a mix of art, science, and metaphor. She explores these connections in mixed media, painting, drawing, and installation. Hildreth’s work has been exhibited extensively across the United States and she maintains a studio in Portland, Maine.

Juliet Karelsen received an MFA in painting from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. In 2015 and 2016 she participated in fiber workshops at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle, Maine, and began experimenting with various form of stitching, embroidery, and mixed media. Her work has been shown in Maine, New York City, New Hampshire, Boston, Ohio, and abroad in Spain, Argentina, and Switzerland. She was born and raised in New York City and has been living in Maine (mostly) since 1991.