by Julie Poitras Santos

When he closes his eyes, Pablo Valiente can still hear the deep silence and persistent background sounds of his native town in the Atacama Desert. “At night I went to bed,” says Valiente describing his childhood in Chuquicamata, “the only thing I could hear was that constant background purring of the trucks that carried material from the mine… While [one] truck was coming another was leaving in a constant becoming. It was with that calming and hypnotic sound that I would always fall asleep.”

Conversations with former mine workers and inhabitants of the town of Chuquicamata, Chile, inform artist Daniela Rivera’s recent exhibition Labored Landscapes (where hand meets ground) at the Fitchburg Art Museum. Entering the galleries of the Museum, you are immersed within a dark cavernous space; the large gallery has been painted black and three massive unframed canvases are suspended in front of the walls. On the canvases, three large masterfully painted sets of hands, one per wall, float in the vast ground, caught gesticulating as if in the middle of conversation. The work is painted so the hands are highlighted; what little the viewer can see of the body recedes and disappears in darkness. The scale of the figures, if completed, would spill off of the paintings and tower over the building.

Chuquicamata, or Chuqui, is home of the largest open pit copper mine on the planet, an extraction so expansive it can be seen from space. The anonymous giant hands in the installation of paintings seem to apprehend this scale and confront it with their profoundly silent speech. While copper has been extracted for centuries from this area — a mummy from about 550 A.D. was found trapped in an ancient mine shaft in 1889 — the mining practices of the twentieth century, and in particular that of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, have utterly transformed enormous swaths of land; the Chuquicamata mine is nearly three miles long, two miles wide, and over 3,000 feet deep.

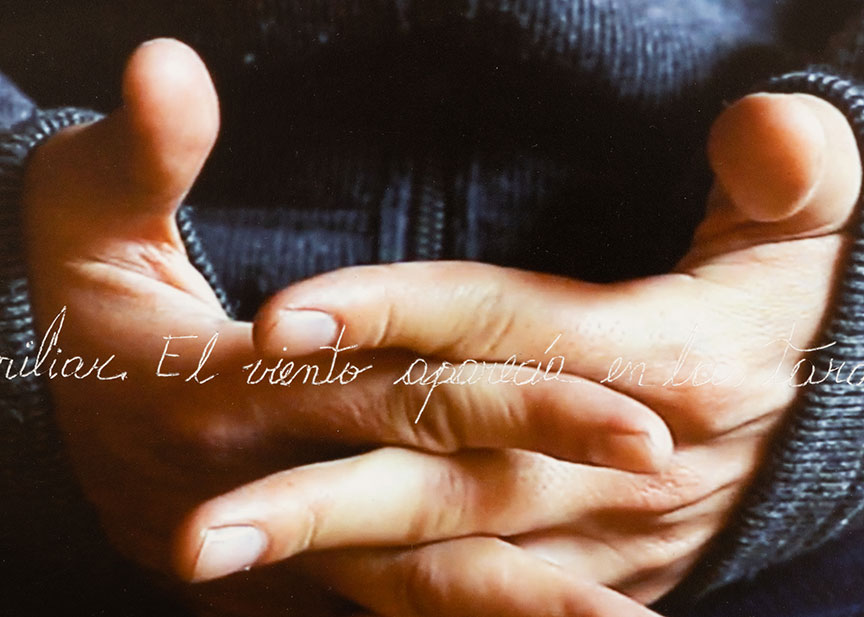

The mining camp of Chuquicamata evolved into a more permanent town for mine workers and their families in the early 1900s. But from 2004–2007, the town of Chuqui was moved by the current company, Codelco, due to mine expansion and environmental concerns. Through Rivera’s work reflecting her conversations with mining families, and specifically with Pablo Valiente and Hilda Fazzi, we are introduced to Chuquicamata, north of Santiago in the hot, dry heat of the Atacama Desert. In a small transitional gallery space, a series of photographs of gesticulating hands — presumably those used as models for the larger paintings — are inscribed with text from these discussions. Fazzi recounts her enormous sense of loss, and the distance she experiences from the home where she raised her children. She recounts, “We were the last to leave Chuquicamata… The whole town was relocated to Calama, all the residential area… Chuqui was no more, and my memories stayed over there… There was no way to resist relocation, and the burying of my memories.”1

Rivera’s artwork foregrounds the stories of the laborers and their families who worked the mines and created the community of Chuqui. In conversations about extractivist histories it can be easy to simplify critiques, pointing away from complicity with and naiveté about distant decisions and livelihoods. While the inhabitants of Chuqui owned nothing of the town, it felt as if they did. The town’s erasure left its inhabitants without their history. “The transfer to Calama mark[ed] the end of an era of paternalism in Chilean mining… But for the miners it [was] the painful end of a sheltered existence.”2 That existence began in the early 1900s with the Chile Exploration Company, funded by the Guggenheim Group, which sold the mine to Anaconda Copper in the 1920s. While nationalized in 1971, the new company maintained the former colonial mindset and paired methods of social support and irresponsible environmental stewardship.

Rivera’s work considers these histories and recenters them from the point of view of the workers whose lives remain deeply connected to the mine in complicated and personal ways. In two other installations in the museum, White Noise and Tilted Heritage, Rivera has inscribed the walls with abstract copperpoint line drawings, filling in shadows and accentuating perspectival views. One can imagine her repeated gestures and the scratching sounds of mark making on the walls, hypnotic and calming, reflecting and revealing a new kind of labor associated with the very copper extracted from the Chuquicamata mine: a labor of listening, remembering, and telling stories of those who worked and lived in Chuqui.

In a nearby gallery, a large cube lists perilously away from the viewer like an open mouth. Dramatically lit, Tilted Heritage confronts the viewer forcefully with its silent opacity. The cube is constructed of a series of canvases clamped together with their backs turned toward viewers, who are invited to carefully bend and enter the structure in order to see the paintings on the other side. Inside the open-topped structure is an abstract material surface, gray and textured; the canvases are covered with ash, some of which slides off the back canvas making a small line of dust on the floor.

The work references a major fire in Valparaiso, Chile, in 2014 which extensively damaged the city. Rivera sought to express the distance she felt from her home while witnessing this event from afar. The theatrical lighting and raking shadows construct a kind of stage — a space for your body to enter and for a kind of intimate interior viewing to occur. Viewing the work alone, quietly inspecting the deposits of ash in the tilted cube, the work resounds with emptiness. There is no sound of flames or sirens, no escaping shouts, just a residue of ash. The cube becomes a formal monument to a past. As with the vast room of gesticulating hands, the viewer is placed at the very center of this absence, physically and psychologically located in a space of loss, both silent and speaking with clarity.

Daniela Rivera‘s Labored Landscapes (where hand meets ground) was on view at Fitchburg Art Museum from September 21, 2019 through January 12, 2020.

Fitchburg Art Museum

185 Elm Street, Fitchburg, Massachusetts | 978.345.4207

Open Wednesday–Friday 12–4pm, Saturday–Sunday 11am–5pm, and first Thursdays of every month from 12pm–7pm.

- The former site of the town of Chuquicamata is now the site of waste material disposal from the open-pit mine. See Louise Egan, “Chile Company Town Goes Dust to Dust,” The Washington Post, February 1, 2004. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Julie Poitras Santos is a visual artist based in Portland, Maine. Also a writer, her research interests include the relationship between site, story and mobility, and often involve areas where art and language intersect. She works as Director of Exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art.