by Alana Dao

For as long as I can remember, I imagined I would be a mother. For as long as I can remember, I also imagined I would be a writer, an artist and a creative. I was never aware that these two things are often thought of as mutually exclusive. But when it comes down to it, there are realities that one must face when trying to intertwine the two.

Practically speaking, many art openings, exhibitions, and other functions occur at night, long after I’ve put my daughter to bed. If an event happens to be earlier, I am often too exhausted or can’t find childcare. Running around with a young child is tough work: carrying a 20+ lb. toddler on my front while carrying art work on my back takes an emotional and physical toll. Scrambling to find childcare so I can go to a meeting is tough. Leaving my daughter with others, even when they are capable and loving, breaks me. Not addressing these difficulties is hard but addressing it as a handicap is the hardest.

I’m an arts administrator and writer, and the other day I had to deliver and install art to Peaks Island. I had planned to meet the artist in Portland but as both of us had small children in tow, plans changed. I waited for the ferry at the terminal in the height of tourist season. Busy, hot, and sticky, I did my best to entertain my daughter with flowers, sandwiches, and hats. In many ways, it would be a lot easier to just stop and I think about this a lot. Would I be a better parent if I gave up the studio practice? As a believer in community and supporting others, this seems impossible. I just wouldn’t be happy, personally and professionally. After running around, installing and organizing with one hand and the other trying to keep my daughter happy while pushing bedtime, my nerves were frayed. That afternoon left me with the feeling that women/mothers/artists are constantly being pulled at, literally by our children and figuratively by those who often don’t realize the isolation of motherhood and balancing artistic work with the work of parenting.

It is often said that many subjects that become a national issue are first addressed by artists through their work. In the past few years, the subject of parenting and children have begun to arise in contemporary discourse, particularly in conceptual art, writing, and academia. As other women artists with children, both nationally and locally, are confronted with issues of women’s rights and paid leave, these themes are also becoming subject matter in their artistic practices.

Artist Lise Haller Baggesen coined the term “mothernism” in her recently published book of the same name. Mothernism, as she writes in her manifesto of sorts, “aims to make mothers and mothering visible, audible, and palpable, outside but particularly inside of the visual arts.” 1 In an interview earlier this year, Baggesen commented:

Particularly in the art world is where people can say they don’t like children, or don’t care about them. I find that quite aggressive that you are allowed to say it. Not that everything needs to be for children or about children (a lot of art is not accessible to children, nor should it be), but I think they are so often left out of the feminist discussion and I think that is a loss. I don’t see how we can talk about a future feminism without thinking about the kids. 2

I agree. Having worked in the arts in various cities in the United States, it seems as though having children is not only frowned upon but also that parents must fight for legitimacy as artists. Simply put, artists with children (women artists in particular) have historically been and still are not taken seriously. The subject of children and parenting remains largely unaddressed and invisible as artists and academics fight to stay present and relevant.

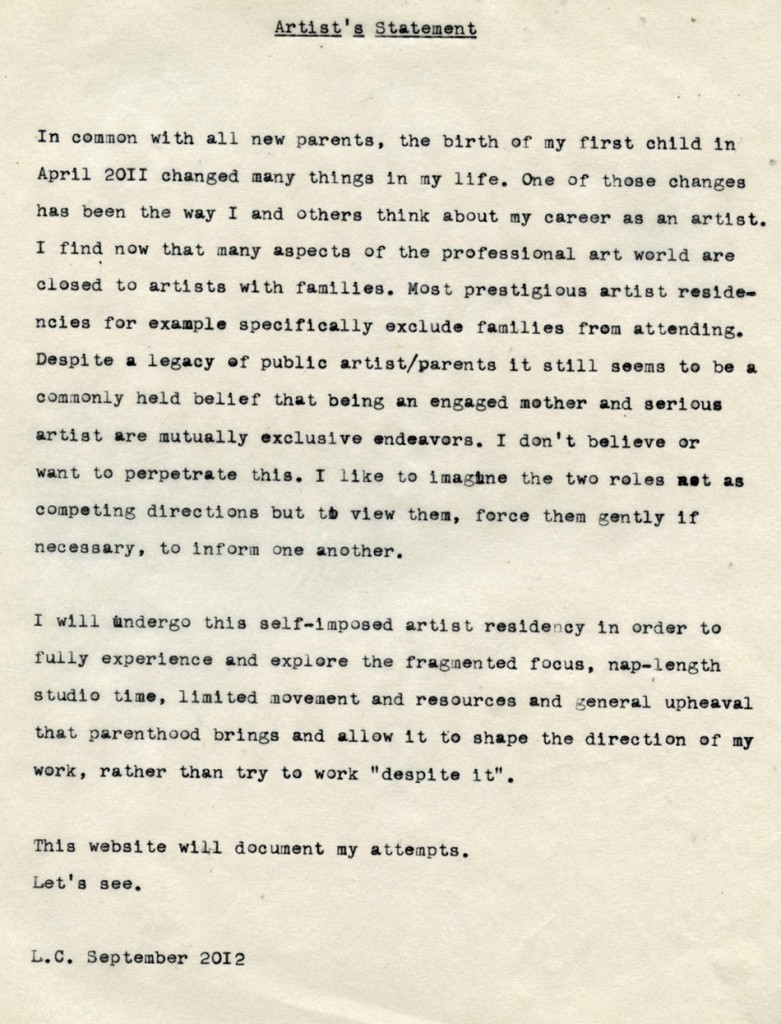

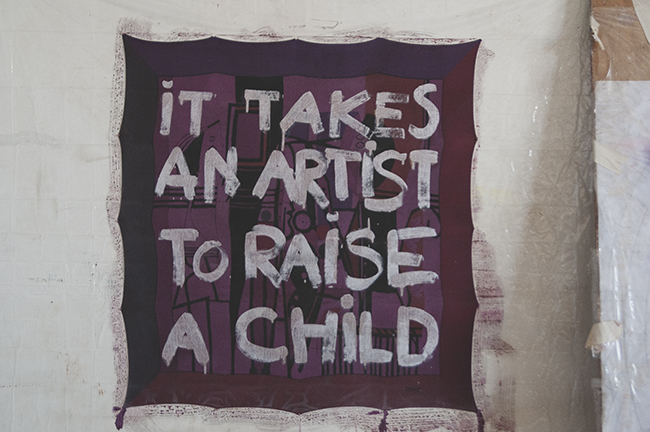

Highlighting the presence of children and fighting for visibility of mothering and the innards of domesticity is also a recent project of Conceptual artist, Lenka Clayton. Based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Clayton established the Artist’s Residency in Motherhood after the birth of her first child. Her Artist’s Statement reads as follows:

Set firmly inside the traditionally “inhospitable” environment of a family home, it subverts the art-world’s romanticisation of the unattached (often male) artist, and frames motherhood as a valuable site, rather than an invisible labor, for exploration and artistic production. Artist Residency in Motherhood provides the artist with a studio, materials, a travel allowance, monthly stipend, studio assistance, mentorship and accountability. For the 227 days of the residency the fragmented mental focus, exhaustion, nap-length studio time and countless distractions of parenthood as well as the absurd poetry of time spent with a young child will become the artist’s working materials and situation, rather than obstacles to be escaped from. 3

Clayton’s residency is funded through the Sustainable Arts Foundation, an organization that supports artists and writers. With a mission to financially support parents in creative industries, the Sustainable Arts Foundation is the first of its kind in the United States, recognizing the difficulties and realities of raising a family while pursuing creative work.

As these movements take hold in larger cities, what is happening closer to home? Maine is making a concerted effort to attract more young creatives to its urban areas, particularly to Portland and the surrounding area. Many artists I know, who happen to have children, chose to move to Maine upon deciding to start a family citing the state’s accessibility to larger cities while maintaining a more low-key lifestyle and being part of a lively arts scene. Whether it be painting, designing, or writing, mother-artists live, work, and care for their children while maintaining an artistic practice; I know no less than eight artist acquaintances in Maine who have children under the age of 2. But if what Baggesen says is true — that children are often left out of the feminist discussion, especially so in contemporary artistic practice — what can arts culture do to support artists with families? And more specifically, how is Maine going to sustain and encourage the growth of creative professionals as more and more young artists, designers, and makers decide to have children?

Jessica Townes George is a successful artist, arts administrator, and mother currently living on Peaks Island with her young daughter. Her work brings her to islands as her paintings investigate the beauty of nature and the intimacy of connection to the land that surrounds us. The importance of raising her daughter on an island in Maine and being “a good example of what it is to focus” are what drives her as not only a mother but also an artist. Her role as a mother bleeds into her studio practice which focuses on “re-purposing worn out objects, and crafting things to warm and calm the heart.” These are also subjects she teaches her daughter through making art. 4 Unlike Clayton’s work, George chooses to include her daughter in the process rather than as subject matter. For her, motherhood has changed the way she thinks about medium, materials, and process: “As my daughter grows, I realize I am working with someone who is coordinated but needs direction in order to use materials safely and carefully.” Having the time to teach her child and to produce work is also an issue that surfaces for many artists.

…I think about this a lot. Would I be a better parent if I gave up the studio practice?

Another artist and mother I spoke with, who prefers to remain anonymous, resides in Coastal Maine with her young son and partner and vocalized similar thoughts. When she does have time for her studio practice, she often feels a pull to do other things, such as clean the house. She had, for a while, a studio space at an artist-run collective but had to give it up because she could never find childcare and didn’t want to bring her toddler son, fearing he would get into something or damage another artist’s work. She would sometimes go in the evening when her partner returned home from work, but admitted this was not ideal. “Sometimes this is the only time we had together and it felt selfish to leave the house. I was beginning to pay for a storage space instead of a studio space.”

As a mother and artist myself, I can certainly relate. In the first year of my daughter’s life, I would write during her naps and, when on a deadline, I’d often have to decide to disregard the dirty dishes in the sink or not take her to a playgroup in order to get complete my work. I felt guilty for this, worrying I was harming my daughter’s well-being by attending to my own matters. But during storytime at a local library, I had a conversation with a freelance artist and designer with a son around the same age as my daughter. She told me she kept toys under her desk and would have her son play there while she worked. We laughed as she jokingly told me, “Sometimes it boils down to: should I work or shower?”

Women/mothers/artists become more informed throughout motherhood. The intense self-reflection impacts and changes one’s art practice in both function and form. As George puts it, “The realities of working with a child consist of a new awareness of how you are working with and around someone else.” This new awareness is a skill, an acquired thing that can perhaps further one’s artistic practice, restructuring and constructing a new way of working.

How am I supposed to further my artistic career for the sake of my child while caring for my child?

Parenting creates a paradox: how am I supposed to further my artistic career for the sake of my child while caring for my child? I am a bad mother if I leave her, I am a bad worker/artist/mother for not taking care of a career that supports her. It is apparent that motherhood has changed my life, so why should it not appear, publicly, in our artistic lives? In one of my very first classes in graduate school, a professor told the class that the most important thing to do was to “be selfish” in reference to our academic and artistic pursuits. This is, perhaps, one of the best pearls of wisdom I wear as I move past graduate school into “real” life, wandering and attempting to find what it is that I desire professionally.

Being selfish to our artistic and emotional needs, in turn, nurtures our children’s artistic growth, allowing them to see and understand the importance of creating and making. By being selfish, I (like many other mothers I know), am teaching my child that art matters. What you do and make are important regardless of any mistakes you make or how profitable it is. To have opportunities like the Artist Residency in Motherhood and texts such as Mothernism is to confront the fact that artists have children, love them, and nurture them. We are supporting the next generation of wanderers, artists, and pioneers. Let’s address “the mother shaped hole in contemporary art-discourse” 5 by casting a larger net, working towards inclusivity and sustainable resources for artists with children in Maine and beyond.

- Lise Haller Baggesen, “UMAMI: United Mothernist Artists Manifest Illuminisms”, Mothernism. https://lisehallerbaggesen.wordpress.com/mothernism/umami/ ↩

- Kate Sierzputovski, “Lise Haller Baggesen’s Disco Feminism,” Inside/Within. (March 2015) http://www.insidewithin.com/LiseHallerBaggesen.html ↩

- Lenka Clayton, Artist Residency in Motherhood. http://residencyinmotherhood.com/about-the-artist-residency/. ↩

- Interview with Jessica Townes George, August 2015. ↩

- Lise Haller Baggesen, “UMAMI: United Mothernist Artists Manifest Illuminisms”, Mothernism. https://lisehallerbaggesen.wordpress.com/mothernism/umami/ ↩

Alana Dao is a writer and maker residing in Portland, Maine with her husband and young daughter. She received a MA in Visual and Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA in Spanish and Latin American Studies from Smith College. She is currently a contributing writer for the online publication Dilettante Army and the Co-Founder/Executive Director of CSArt Maine, the first community art share program in the state.