by Helen Greenbriar

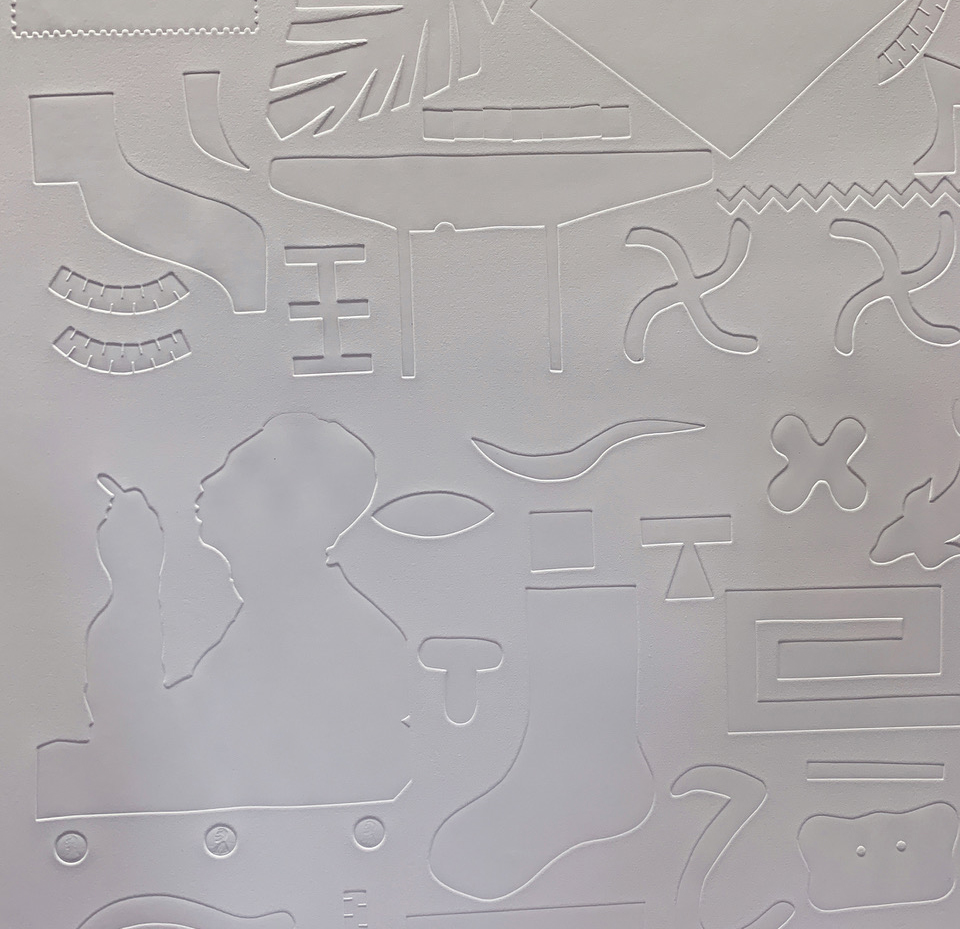

There is quite a lot to see in the 2015 Portland Museum of Art Biennial, You Can’t Get There From Here. This exhibition of contemporary art, which is on view until January 3rd, brings to mind a show at an old-style expo hall1, whose grand facade is basically a giant receptacle for large quantities of similarly-themed objects. Upon entering, I was instantly stopped by a forest of glass vitrines on plinths to my left and a jumble of third-graders to my right. The low-ceilinged entry room was filled by the voice of a museum docent, both booming and shrill. “We don’t just consider this craft any more, this is art!”, she said to the children, gesturing toward the baskets that filled up the vitrines. The children blinked and looked around. The vitrines themselves do seem to indicate the formality of “art”, but the large number of baskets inside suggest the rejected “craft” reading, due only to the craft-show-like quantity of examples — individually, the baskets are breathtaking. The work of Theresa Secord particularly stands out in its abstract intensity. As a group, they are difficult to engage with due to the way in which they are exhibited, and this forces them to compete with the other works of art in the room. It was a wonderful curatorial choice to include the Wabanaki baskets; the clarity of this intention is somewhat dimmed by the installation.

This sense of craft fair, flea market, or other mass assembly of objects grows as one moves through the exhibition. Lovely gestural line paintings by Susan Harnett fade into an autumnal wallpaper behind the above-mentioned glass vitrines, which are quite tall. Lois Dodd‘s irreproachable oil paintings are also obscurely situated on a wall behind these vitrines, where they, like the baskets, are crowded together. Their usual impact — that of lightness, confidence, and painterly insight — is minimized by their proximity to a neo-Neoclassical oil portrait by Brett Bigbee, which is the same small size as the Dodd paintings. Who can stop looking at a painting as quasi-realistic and mesmerically executed as the Bigbee piece? Looking back at Dodd’s paintings, the searing intelligence of her brushwork seems to be missing something in comparison to the glassy smoothness of the Bigbee portrait. Perhaps fresh vegetables and ice cream do not belong on exactly the same plate, or at least not in such a way to suggest that they are essentially the same thing.

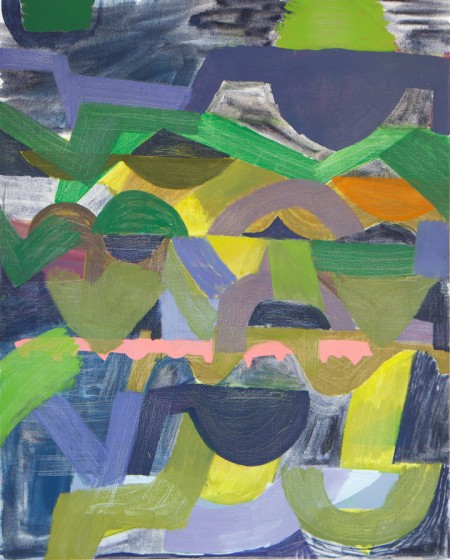

Other works in the Biennial are nearly as wonderful as the Lois Dodd paintings. Meghan Brady‘s series of light-filled abstract oil paintings evoke the vertiginous aura of the Delaunays, but again this work is somewhat masked behind the formally similar sparkly resin sculptures of Richard Van Buren. The docent and children continued to file through the space (“Anybody know what a thicket is?” “It’s a bush.” “Okay!”). In the middle room, the jumble-sale aesthetic thins out a bit; works by John Bisbee, John Walker, Caroline Lathan-Stiefel, and George Mason form a wide-open composition of circles, squares, and linear marks. However, moving around the corner subjects the viewer to further challenges to viewing the artworks. The back corner of the gallery is a (very colorful) traffic jam of work, including a yellow ceramic object by Miles Spadone that blocks a sprawling installation by Emilie Stark-Menneg. Stacy Howe‘s incredible large-scale black-and-white drawings are hung in tight salon style in a corner; they need a great deal more room for her intricate linework and convoluted symbolism to unfold properly for the viewer. A Gideon Bok interior suffers from a similar, though less constricting, lack of space; at least with the depiction of a room, with its recessive perspectival space, the eye has the option of moving in even if it cannot move around.

In the dividing section of the central room, a large and airy conical Anna Hepler sculpture floats down from a mezzanine to hoover up the tension for a moment; we are then puffed back out and shuttled into a smaller space, which is once again crowded by a tangle of artworks. Photos wash up thickly on the shore of the left-hand wall (family narratives by Justin Kirchoff and beautiful natures-mortes of a compost heap by Christine Collins stand out), and are subsequently blocked by a hanging sculpture by Randy Regier. By this point, the senses of the museum-goer have been stretched thin, nerves are brittle, and the exit is in sight. As a result, an interactive video piece to the right, by Owen F. Smith, is palpably uninviting. I preferred not to lie supine on the floor and make my own body into part of this generally taxing sensory experience. On the way out the door, a sneak appearance by another Bok painting leads the eye into a space that, while it exists only as the illusionistic interior of an oil painting, is so much more warm and generous and promising than the cacophonous space of the recently-exited gallery that one cannot help feeling a sense of escapee’s relief.

Perhaps what the current Biennial needs is just less of itself — say, twenty-two artists instead of thirty-two — or a physical space more analogous to that of an actual expo center: the Cross Insurance Arena, for example, or the Circus Conservatory. The Biennial is no longer juried; the curator, Alison Ferris, had full control over the content, and so the number of artists and pieces could theoretically have been matched to the constraints of the space. Ferris’s curatorial choices are intelligent and well-considered, but with so much stuff in the room, the aura around the individual artworks dissolves, and the show begins to seem precariously similar to the simple amassing of a large number of objects. The overall thickness of work in the exhibit leads the viewer to the kind of perceptual blockage hinted at by the show’s title. If the phrase you can’t get there from here epitomizes the native Mainer’s stubbornness, recalcitrance, and capacity for dissembling, it is also a suitable phrase for summing up the viewer’s experience of the strongest work in this group show. The best artworks themselves seem to be taking the role of the beady-eyed old man in the moth-eaten Red Sox sweatshirt, pointing the wrong way at a crossroads in the night, in a forest dense with thickets.

You Can’t Get There From Here: The 2015 Portland Museum of Art Biennial continues through January 3, 2016.

Portland Museum of Art

7 Congress Square, Portland, Maine | 207.775.6148

Open Tuesday, Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday 10am–5pm, Friday 10am–9pm, Third Thursdays 10am–8pm. $12 adults, $10 seniors and students, $6 youth 13–17, $5 surcharge for special exhibitions. Free for children under 12, members, and everyone on Friday evenings 5pm–9pm.

- In Harrisburg, PA, there is a large expo center, with Assyrian-inspired bas-relief details of marching farm animals decorating the Depression-era exterior. Driving past this noble structure, one imagines a kind of archetypal farm exposition that is as illuminating and intellectually compelling as this authoritative building and its decorations suggest. Upon further research, one finds that it is indeed used for horse and 4-H shows, as well as the Great American Outdoor show (sponsored by the NRA), the Pennsylvania Christmas & Gift Show, and various flea markets. Naturally, the dignified authority that the structure itself radiates is not always matched in tenor by the events it hosts, nor should it be. The purpose of the expo center is the display, on a large scale, of a thematic grouping of objects that are representative of a very specific (agricultural, commercial, etc) concept. ↩

Helen Greenbriar lives in Portland, Maine.