by Jacob Fall

We all know these names. The dead: Barnet, Bellows, Langlais, Hartley, Homer, Marin, Nevelson, Porter, Welliver, Wyeth, Zorach. And those still living: Dodd, Estes, Indiana, Ipcar, Jacquette, Katz, Wyeth. Whether canonical, critically-acclaimed, or vastly popular, certain artists have become linked to the state of Maine in our collective mind. This landscape, the flora and fauna, the people and the things they built.

In his will, the late William Thon specified that “a Maine artist is a painter who has lived and worked for substantial periods of time in the State of Maine.” That pretty much sums up the view of folks outside the art world (“civilians”): a Maine artist is someone who makes landscape pictures, usually with paint. Our landscape is beautiful (and also sublime, picturesque, and where things have been built, sometimes quaint or kitsch) and that is one of the reasons we, or our ancestors, chose to live here. But there are many more varieties of artist working in Maine: Wabanaki basket makers, stone carvers, digital media artists, performers, conceptualists. The significance of regional identity for artists’ production and reception is one of the hardy perennials in the lush (soggy?) meadow of professional conversation in our studios, salons, and saloons.

A recent and more formal example of this discourse can be found in the Maine Policy Review, where George Kinghorn, director and curator of the University of Maine Museum of Art, has published a round table discussion between himself, artists Lauren Fensterstock, Philip Frey, Anna Hepler, and curator Suzette McAvoy. You’ll want to read it:

George Kinghorn: When I first arrived at the University of Maine Museum of Art [UMMA], I encountered a few individuals who were puzzled that the museum’s focus was not exclusively Maine art. I explained that it has never been the mission of UMMA, and the majority of works in the collection are not by Maine-based artists or of Maine subject matter. I have always maintained that as an academic museum, focusing primarily on exhibiting and collecting works created since 1945, our mission is to introduce citizens including Maine artists to a diversity of creative approaches being explored by artists from all over the country. Also, it’s important to place significant Maine artists within a larger and more global context and, I hope, through exhibiting at UMMA, their works will be introduced to larger art markets.

Suzette McAvoy: No, we’ve always defined our mission as showing artists with strong ties to Maine. There are so many artists who don’t necessarily live here year around, but have ties to Maine. They may not be representing Maine in their work, but their art is influenced by a deep connection to Maine. In the recent biennial, there’s conceptual art, installation, video, and traditional painting. Works based on nature is a common thread; this may be the Maine connection.

Lauren Fensterstock: I’ve lived here for 14 years. I consider myself a Maine artist and love living here, but being from Maine is not my primary identity. Does that mean that I have to make the content of my work about Maine? I find that I have a complex identity that is the result of many facets of my life. I think with any system of categorization, there’s simplification. What is problematic for me is that some exhibitions in Maine such as biennials and other shows are grounded in these categories or distinctions. These locally focused criteria may cut off possibilities for greater exchange and dialogue with the rest of the world.

Philip Frey: The question that I’ve been pondering the last couple of years is: If a Maine artist is producing works with Maine subject matter or that may be labeled “Maine art,” can they be taken seriously in art markets outside the state?

Anna Hepler: I’m not interested in being labeled anything. We need to distinguish between what the market asks and needs in order to sell and as a way to secure its audiences, versus what we experience as artists living here. There is a prejudice that regionalism is associated with folk art and craft; it’s a different market altogether. If regionalism is a cloak an artist wears for whatever reason, it will inevitably exist as a prejudice in terms of trying to shift work from a regional market to an urban and international one.

Where do we go from here? The topic of regionalism is bound up with and interpenetrated by other topics such as opportunities to show work, the art market, the growth and decay of commercial gallery scenes (Portland may be adrift, while it’s steady as she goes in Rockland), the existence or absence of a collector class, or the influence of museums and non-profit spaces. New York casts a long shadow, as Mariah Bergeron pointed out in the inaugural issue of this publication. Audience commentary at a recent panel discussion at the Portland Museum of Art (“Regionalism and Contemporary Artists in Maine: Opportunities and Challenges” with, once again, Kinghorn, Fensterstock, Frey, and Hepler) touched on many of these related issues. Perhaps this is an unanswerable question.

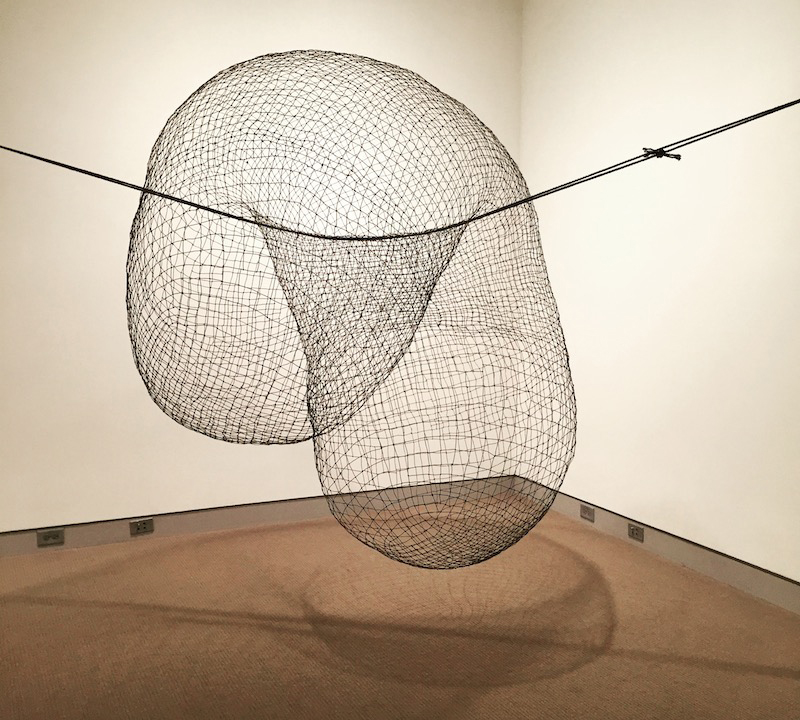

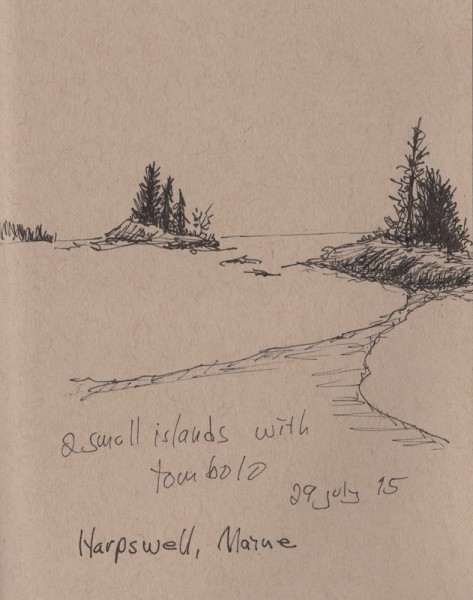

Consider the images accompanying this article: a sketchbook page and a sculpture made by artists who primarily make abstract work and who prefer not to be labelled as “Maine artists”. James Chute’s pen drawing of islands includes a tombolo, a double beach. Anna Hepler’s Double Hung has recently been on view at the University of Maine Museum of Art. One can reject the label but one can not escape the reality of being an artist and living in Maine.

I recall a letter writer chiding the editor of the Maine Times (a now-defunct weekly newspaper best described as progressive but not alternative) with these words: “Maine is a place to live, not a religion.” My answer, which may be no more than a quip: all labels are limiting, especially the ones that fit.

The first half of this piece, “‘Maine’ Artists? Beginning to unpack regionalism”, a survey of artists, curators, and critics on the label of “Maine artist” was published in Vol. 1, No. 3 of The Chart.

Jacob Fall hails from Willimantic, Maine. He studied anthropology and art history at New York University. He has occasionally lectured at the Greenwood Cove Institute for Boreal Limnology.