by Maia Snow

A while ago when I was adding Greta Bank’s phone number into my contacts I accidentally spelled her name as “Great.” I have never changed it. Now, as I watch Greta enter through the doors of LFK to join me at the bar, it is impossible not to notice the unique swagger she carries, rocking a cashmere sweater and black hair streaked with white blond, reminiscent of summer humidity mixed with salt from snowy roads that have just been plowed. As she takes her seat next to me, I cannot help but smile in anticipation of the conversation that’s about to take place. We’ve talked extensively about her art, her practice, and the grant she’s just won — Greta received a 2015 Emerging Artist Grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation, a $12,000 grant to recognize artistic excellence and support further artistic endeavors. But this meeting has a different tone; now I must ask more formal questions.

After greeting me with a hug that always feels like I have not seen her in months, Greta sits down and immediately notices a crystal necklace that my friend is wearing: “I’ve been obsessed with round quartz crystals!” she exclaims. “Quartz crystals are oscillators that used to be used for radios and gathering frequencies.” Without skipping a beat she continues, “When quartz crystals are mechanically manipulated they have an electric charge. I want to use them for some sort of time travel element in one of my next projects.”

So it begins.

Maia Snow: How excited were you when you found out about the Joan Mitchell Foundation award?

Greta Bank: I wasn’t excited at all. I was really burnt out and the odds were very tough. At some point I decided I wasn’t going make the cut. I went to a field and had a good cry. There was a lot of grief in recognizing I was going to have to keep doing it by myself. Then I went home and got the (good) call, and cried some more.

When I did my interview [with Joan Mitchell Foundation] I talked about Powerball. How it’s nice to buy a ticket and leave it in your wallet and never check to see if you won. That the potential is better, so they shouldn’t pick winners, just let us all enjoy the potential. It’s a serious problem for artists, thriving while feeling deprived of acknowledgement.

I want to be a pollinator, I want to bring things back here in some way or somehow.

MS: What does it mean for you to be an artist, a creator, and thinker?

GB: It’s a title that I guess I can admit I’ve earned but I don’t really feel comfortable with titles. They’re static.

MS: What about a parent, a mother who is an artist?

GB: More titles! I struggled more with this a number of years back when I had to convince people how deeply my children fuel my purpose. I think folks are coming around.

MS: What did you want to be when you were a kid?

GB: When I was 12 I realized I wanted to be a painter. I spent two decades training in oils. I am pretty upset that I’ve moved away from that, I told myself it was temporary for a long time… I am seriously thinking about what it means to leave something like that behind. It’s beautiful stuff and I’m making art about it.

MS: What is your art about?

GB: Science fiction and dystopia are the loves of my life. A lot of my art is connected to the philosophy of science fiction, taking something that is historical or topical or a purely aesthetical or material reference and layering it in a way that causes an experience to the audience where they would have to question the human condition. It’s a philosophy of how to connect to everything.

MS: Go on…

GB: Science fiction could become very kitsch. But there are clues and hidden metaphors that talk about and are related to the human condition. Zombies. I think zombies are a subconscious prep for Mob Culture. Which is something that, we as a society, don’t have a lot of experience with, but we are aware of it, here in the United States.

MS: Could you talk more about the zombies? Often I think the idea of sci-fi and zombies are so far removed from reality.

GB: The idea of zombies is this fear and anxiety of being run over and consumed by your own neighbor, by the people you know. This notion attaches itself to the much more fragile membranes of the infrastructure disappearing. Which happens all the time all over the globe. Historically and presently, there are millions of people who are at this exact moment, or for generations, have had to envision and witness that.

MS: Like genocide?

GB: Yes. But not limited to. What science fiction does best is to open us up to the things that in fact are real. Sometimes it is about speculating about the future. There is some evidence of how many things we have speculated about that have actually come true. But what most sci-fi is is a metaphor for what is happening all around us all of the time. In ways that people don’t identify with or can’t see or don’t want to see. In a way, making us question the world’s worth, as if trying to eradicate morality, creating dystopia.

MS: Is there a complete removal of morality in dystopia?

GB: No, not always. The writing in science fiction doesn’t always have to be about the world falling apart.

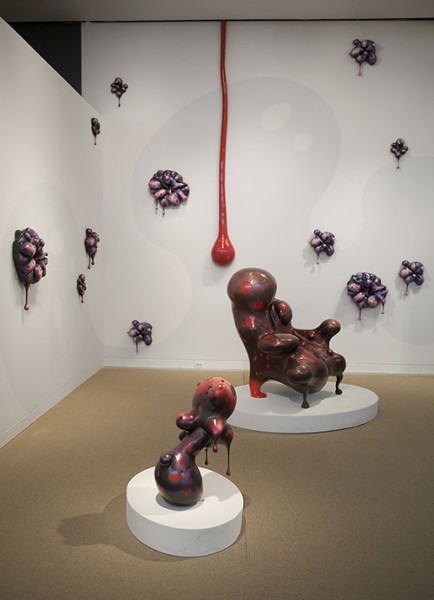

The following evening I received a message from Greta — well, from “Great” — asking to help her unload a car full of mannequins that she has picked up from Gap. She sent me a picture of her car being stuffed with babies, toddlers, kids, and leg mannequins. On this night the rain was coming down hard as I watched Greta’s car pull up to the studio entrance. The car had just enough room for Greta to be able to drive, the rest was full of fake bodies and limbs. As rain continued to downpour, we unloaded the mannequins into the entryway of the studio building where the pile of fake bodies resembled an image you’d see in history books. Carrying three to four bodies at a time, we started to move them up the stairs and into Greta’s studio on the fourth floor.

GB: You know about the Tutsi and Hutu genocide right?

MS: Yeah.

GB: There is a story of this woman. I don’t want to tell you about it because it’s dark. Carrying these mannequins up these stairs makes me think of it.

MS: Tell me.

GB: There was a body of a woman found in a river. When she washed up ashore there were several babies that were gripping to her legs and arms. She must have been pushed into the river with her kids tied to her. She was probably killed by people she knew. Which goes back to the conversation we were having the other day, about the idea of zombies, and neighbors turning on neighbors. That is what happened with the Tutsi and the Hutu. She must have tried to save the children by raising her legs and arms above the water, or the children that were tied to her must have pulled her under.

This also made me thing of the Rat King. You know about that?

MS: No.

GB: It’s when the rats are climbing on over the other to try to get to a food source and they make a mountain from their bodies, and their tails get all tangled up and they get stuck. They either die or survive like that. I also think this is a metaphor for our social and economical structure.

Often I do not have a response for Greta. I understand the non-linear thinking that somehow always circles back to itself or is able to find where the thought originated or came from. Her thoughts and ideas are projects for and about life, which are based in the history of humanity and socio-political structures.

MS: What’s next for you?

GB: I have a shopping list of stuff that I’ve percolated for a long time, which is a much better word than procrastination. When it’s ready it comes forward. So there are some different works that just need propellant. We’ll see.

MS: Who is your favorite artist of all time?

GB: That is a bad idea. I have favorites but it’s dangerous to put so much weight on them.

MS: Which artists are you looking at now?

GB: I try and surf artists but I’m wary of looking for too long; it just messes me up. I have to be careful. An artist I admire because what he does is so sincere and blows my mind? Jacolby Satterwhite.

MS: What are you reading/read that has stuck?

GB: I haven’t read [Frank] Herbert in years, but I read and loved every book he wrote. The same for Octavia Butler. I haven’t read every Neal Stephenson but they would be a three-way tie. Those writers changed me.

MS: Website?

GB: Did you know my name is a neighborhood in England? We compete for Google top hits. I haven’t updated it in five years. Part of this grant is going to be an overhaul. I have been watching how we use the Internet closely with my arms crossed. I want use what works even if that means skipping the portfolio aspect. I’m still percolating.

MS: I have to ask this for me: does it upset you to know that there is light that is on the visual spectrum that we cannot see?

GB: No…I do get upset at the stars though. Space is so deep.

MS: What advice would you give to an emerging artist?

GB: Beware of currency in all forms, keep your head down and just make the work.

Maia Snow graduated from Maine College of Art (’13) with a degree in Painting. She currently she lives and works in Portland Maine. Her studio is located at the Space Studios in the downtown Portland area.