by Ikram Lakhdhar

Poetry Is Not a Luxury, an exhibition at the Center for Book Arts, is a labor of love from curator Maymanah Farhat that deals with issues of identity, home, war, and immigration. Titled after Audre Lorde’s 1977 essay on the intersections of creativity and activism for Black women poets, this group exhibition brings together a strong roster of more than twenty artists who translate their subjective resiliencies to resist, heal, and transform current socio-political systems. From Cuba to Iraq to China, these artists turn our awareness to relational artistic expressions that emerge in reaction to oppression around the world.

I grew up in Tunisia, a North African country bordering Algeria and Libya — the birthplace of the Arab Spring, which spread to Egypt, Syria, Yemen, and others. Consequently, I apply my lens and lived experience as an Arab Muslim Immigrant Woman of Color to my writing, curatorial, and scholarly practices. As I attempt to draw a deeper understanding of this exhibition by contextualizing it within larger theoretical and historical narratives, I hope to take an introspective focus in particular on the exhibited works of Zeina Barakeh’s Homeland Insecurity (2016), Gelare Khoshgozaran’s Airgrams (2012) and Convergences (2014), Joyce Dallal’s Family Album, Rug and Book (1992), and Helen Zughaib’s Books Without Words (2008).

Joyce Dallal is a first-generation Iraqi-Jewish American; Gelare Khoshgozaran is an artist who was born in Tehran during the Iran–Iraq war; Zeina Barakeh is a Lebanese-Palestinian artist; and Helen Zughaib is a Lebanese-American artist whose family left Lebanon in 1975 due to the outbreak Lebanese Civil War. All invite an exploration of the personal and political impacts of the displacement of war, and expand the potential for transnational relationalities. Their artworks symbolize fractals of hope that are representative of a loose movement and a therapeutic practice of aesthetic justice by artists that live in liminal spaces, creating a sanctuary of knowledge waiting to be unraveled.

The exhibition derives its analytical framework from Lorde’s text of the same title. Using Lorde’s theory as a point of departure, Farhat meditates on the role of artists’ books, broadsides, and zines to “frequently serve as sites of resistance.”1 Speaking about the referential aspect in the level of familiarity that makes artists’ books accessible, Farhat states, “We understand that there is a story to be told whether a work is to be read as a sequence of signifying images, verbatim, or as a written narrative, or as a freestanding three-dimensional object.” Artists’ books can be inherently revolutionary given the ways in which anyone, even outside the art world, can have legible and intellectual access to a copy. However, unless these works are seen in a gallery setting, wide-spread accessibility to these works is still restricted. So then, how can we hold artists’ books to a more common level of accessibility?

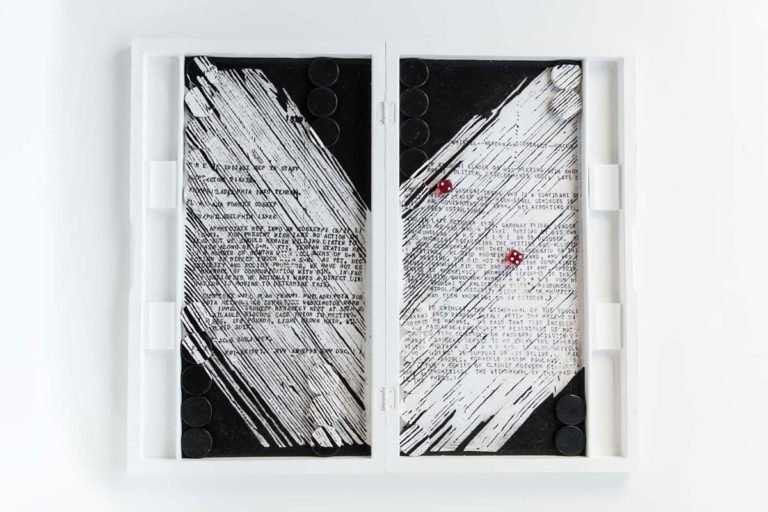

My discussion of accessibility opens to myriad points of entry to political revolution. Gelare Khoshgozaran’s Airgrams and Convergences strike as an alarming reminder of governmental censorship and secret intelligence services, which have enabled the systematic destruction of archives that retain any flagrant information on injustices. When I put my hands on one of the books displayed in Airgrams, a series of paperbacks containing a selection of archives from the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran, I am further reminded of instances in which WikiLeaks circulated information that arguably ignited the Tunisian people’s will to march on the streets in opposition of dictatorship. As I look closer at the installation of Convergences near these books on the Iran-Contra affair, I feel vulnerable. The sight of shredded clandestine material, photocopied and wheatpasted onto a backgammon board — a popular Middle Eastern game — evokes fragile feelings while processing the fact that these secret files are exposed in their servitude to a lucrative and an entertaining game for the common people. The artist is asking: Are you ready to roll the dice?

Homeland Insecurity, an animation by Zeina Barakeh, investigates the various mechanisms of war that cause the fragmentation of the body and the self. Her video shows a group of mythological anthropomorphic characters: figures with Trojan-like horse heads and half-human bodies — Barakeh uses her own body as the template — wear black bodysuits and move in defiance while holding warrior poses. In concert against the backdrop of intense rhythmic instrumental music, the characters multiply and repeat their choreography in a synchronized way, looping within an environment reminiscent of the desert-like Western-imagined territories of the war zone in the Middle East. In the video, we also see broken pieces of plaster with Arabic calligraphic scripts used to decorate buildings, as well as giant cotton balls, alluding to the fall of civilization, culture, and language. The work brings to the forefront the alienation and violence at the core of the homeland security policies. In the wake of conservative right-wing politics in the U.S., Europe, and England, borders are becoming vicious machine-like entities against the advancement of asylum seekers worldwide — water borders are the deadliest.

Barakeh’s animation recalls a film by Gelare Khoshgozaran entitled Medina Wasl: Connecting Town (2018), which I saw at the Hammer Museum’s biennial Made In LA 2018. Medina Wasl examines “the role of fiction and speculation in the West’s construction and representation of the Middle East, and the continued violence enacted through the War on Terror’s conflation of languages, landscapes, cultures, and geographical territories.” In one of the film’s documentary scenes, militants appear dancing a traditional Arabic choreography that suggests the role of femininity within military operations and draws a parallel to Barakeh’s depiction of female warriors. Both of these experimental cinematic works demonstrate the impact of media as it relates to U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, shifting the popular cultural prisms of Western domination of Islamic states.

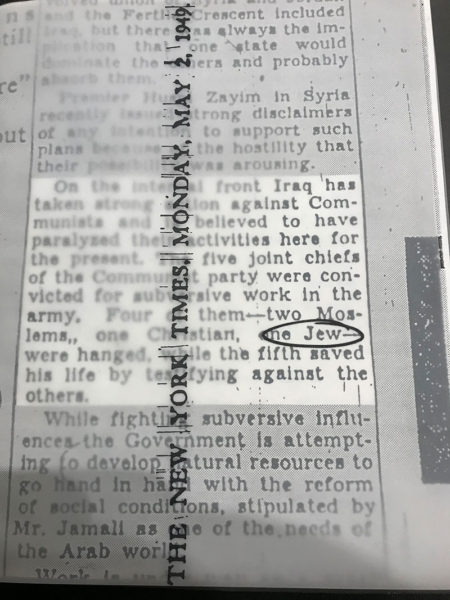

Akin to “Lorde’s understanding of poetry as ‘an illumination’ and/or means of problematizing dominant narratives,” as Farhat notes, artist Joyce Dallal considers the subjectivity of an Arab Jew to negate hegemonic understandings of a single-view history of refugees. Family Album, Rug demonstrates a moral challenge to a common Islamic religious object found in the homes of most Muslim families. Adorned with a diverse set of calligraphies that represent Arabic, Hebrew, and Kurdish, these texts are overlaid with a mesmerizing collage of American newspapers clippings in English. In her interpretation of the Islamic prayer rug, Dallal complicates the normative belief that reduces Iraqis to having one single ethnicity and mother tongue by creating a visual resistance through this tapestry of her family’s diverse identity. Similarly, in Family Album, Book II, Dallal introduces a rare controversial piece from The New York Times, which states that the Iraqi government had issued warrants against Iraqi Jewish emigrants to revoke their citizenships unless they returned to Iraq. Another page illustrates a collage of news clippings of stories from the U.S.–Iraqi war, in which Dallal has marked places with notes from her family ties to them. To complicate this book further, Dallal includes a page which recounts the chaos brought by the 1949 official appointment of Israel as a U.N. state. In the same page, she encircles the word Jew.

Transnational feminist and Iraqi Jewish scholar Ella Shohat has taken a relational network approach to take into account the Arab Jew as “an ontological oxymoron and an epistemological subversion” within the hegemonic discourses that are rooted in the form of racialized tropes, Orientalist fantasies, and Eurocentric epistemologies. By recounting her own scholarly narrative, and sharing accounts of her family, mother, as well as archives from her childhood, Shohat looks at layers of identity and history to rebuke the idea of a single narrative of a refugee “Arab-Jew.” Shohat reminds us that to “re-inscribe the Palestinian and the Arab-Jew as the subjects of their own histories mandates the replacing of a single national history with a constellation of inter-connected histories.” Similarly, Dallal’s Family Album series layers personal and archival accounts to build a nuanced context — these testimonies, at the very least, urge a continuous investment in unpacking filial layers embedded within personal archives.

Placed on a pedestal in the middle of the exhibition’s gallery space, Books Without Words, by Helen Zughaib, shows conjoining panels of paintings which resemble a traditional Palestinian embroidery pattern. In the Palestenian refugee crisis, many people have been forced to emigrate and leave their traditions behind. Zughaib’s Books Without Words aims to revive these disappearing patterns to memorialize the Palestinian aesthetic. Here, the artist intentionally chooses to use beauty as a tool for empathetic healing and a symbol of hope. The panels are stitched together with yarn to evoke the fragility and intimacy that these authentically adorned books provide — as opposed to walls — and invite the viewer to think about books as the building blocks, to begin to make real the contents of a justice poetic expression.

Audre Lorde believed that poetry is essential to the life of the marginalized — that it is life itself — as it becomes a source of opposition and consequently the fuel for action. Farhat’s curatorial activism lies in the gesture to elevate artists books to a platform of resistance, or as I see it, a translation of personal resiliencies into artistic expressions in the form of books, zines, illustrations, and media art. The artists in Poetry is Not a Luxury bring our attention to veiled stories and histories from their personal archives and perspectives, building powerful, yet vulnerable, narrative accounts into the forefront of the movement.

Poetry is Not a Luxury, curated by Maymanah Farhat, is on view at the Center for Book Arts through September 21, 2019. The exhibition includes works by Aurora De Armendi with Adriana Mendez Rodenas, Zeina Barakeh, Janine Biunno, Ana Paula Cordeiro, Joyce Dallal, Nancy Genn, Gelare Khoshgozaran, Brenda Louie, Nancy Morejon with Ronaldo Estevez Jordan and Marciel Ruiz, Katherine Ng, Miné Okubo, Martha Rosler, Zeinab Saab, Jacqueline Reem Salloum, Patricia Sarrafian Ward, Jana Sim, Sable Elyse Smith, Patricia Tavenner, Christine Wong Yap, and Helen Zughaib.

Center for Book Arts

28 W 27th Street, Floor 3, New York, NY | 212.481.0295

Open Monday–Friday 11am–6pm and Saturday 10am–5pm

- Maymanah Farhat, Book Arts As Forms of Differential Consciousness, New York: Center for Book Arts, 2019, p.7 ↩

Ikram Lakhdhar is a Tunisian LA-based independent writer and curator.

Online @lalaik and www.ikramlakhdhar.com.