by Frances Barker

To engage in discourse surrounding gender, a solid definition is in order. Gender is most commonly conflated with sex, or thought of as a trait central to our identity/being. In reality, neither is necessarily true. Gender is, functionally, a system of coding other human beings in an attempt to structure nonverbal communication. In participating within this system, we partake in gender as a performance. Art, music, and other cultural institutions function in the same way. We may think of culture as a series of objects or aesthetic pleasures; however, the reality of culture is that it functions as a signifier within the context of a greater language. Culture and art speak to us (literally, though sometimes nonverbally) and perform a function. The artist is the vessel of translation between the symbol of the art and the audience; they create art as a performative act to convey a greater meaning. For example, the paintings of Emily Mae Smith investigate the nature of gender as it is superimposed through performances of object and personhood, as is explained by Judith Butler.

In regards to the two-gender binary, each gender based on the ideas of “masculine” and “feminine” must have certain distinguishing qualities, lest they become the same thing and therefore redundant as signifiers within a greater code of “humanness”. Certain traits are applied to the human structure, primarily anatomical, for if we categorize humans from birth we are forced to do so before they have exhibited any personality traits, leaving us only with categories based on physical appearances. Starting from the most basic (yet cissexist) example many of us are taught, a signifier of female is vagina, whereas penis is to male. From there, we associate secondary sex characteristics with the differences between our bodies — the feminine presence of breasts, more curvaceous figures, or masculine signifiers such as more pronounced Adam’s apples. Once we have been designated as male or female we become socially obligated to perform to these standards, lest we cause other people discomfort by defying their expectations. Of course, these symbols fail to convey much content or meaning beyond just announcing the physical characteristics of our presence; therefore, in order for gender to be an effective tool of language it must have a broader application.

If we are to perform our genders, then, we must utilize symbols to act as signifiers that convey meaning. Thousands of years of cultural development leading to what we now consider the “modern” world have yielded an infinite minutiae of cultural signifiers regarding gender; ingrained in many of us are gendered associations of colors, products, objects, and so on. These cultural signifiers force themselves into every aspect of our lives because they give an object meaning, and oftentimes, appeal — and appeal is important to all commodities, including cultural ones. Art is not only an object, an image to look at, a song to listen to, but another manifestation of communicative language — if we now have, as aforementioned, an infinite minutiae worth of unspoken signifiers, then the most effective way to communicate nonverbal signifiers is through art as a collection of these ideas. Think of, for example, Andy Warhol: by lining up tens of Campbell’s soup cans on a wall as images we see the nature of mass production immediately in front of us and are forced to consider more carefully our reliance on commercialism and materialism. This is, of course, an easy and reductive read of Warhol’s body of work, but nonetheless, is an easily understood starting point for this new iconography of symbols as visual language and signification rather than just for aesthetic purposes.

One could ask, then, how commodities relate to gender. The function of a performance outside of theater is the act of solely selling yourself, or convincing the gaze of others that you truly are a certain thing. Now that hundreds of years have passed that have developed the current recognition of the gender binary-spectrum, we are conditionally obligated to uphold these standards. Through the previous notion of gender being projected onto inanimate concepts — like toys or colors — it is our understanding that we must project gender unto ourselves. In this way we are not only assigned gender based on physical signifiers as an organizational code, but we force ourselves to perform it as well, through our actions, physical presence, and language.1 As we sell art, objects, and other things, we sell our performance of gender. We reduce our identities to something as simple as a Marxian commodity: “an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another.”2 The function of language is to use performative acts or signifiers to convey meaning to satisfy a desire involving those outside of ourselves. Gender, according to this definition, is both a language and a performance. Art functions the same way.

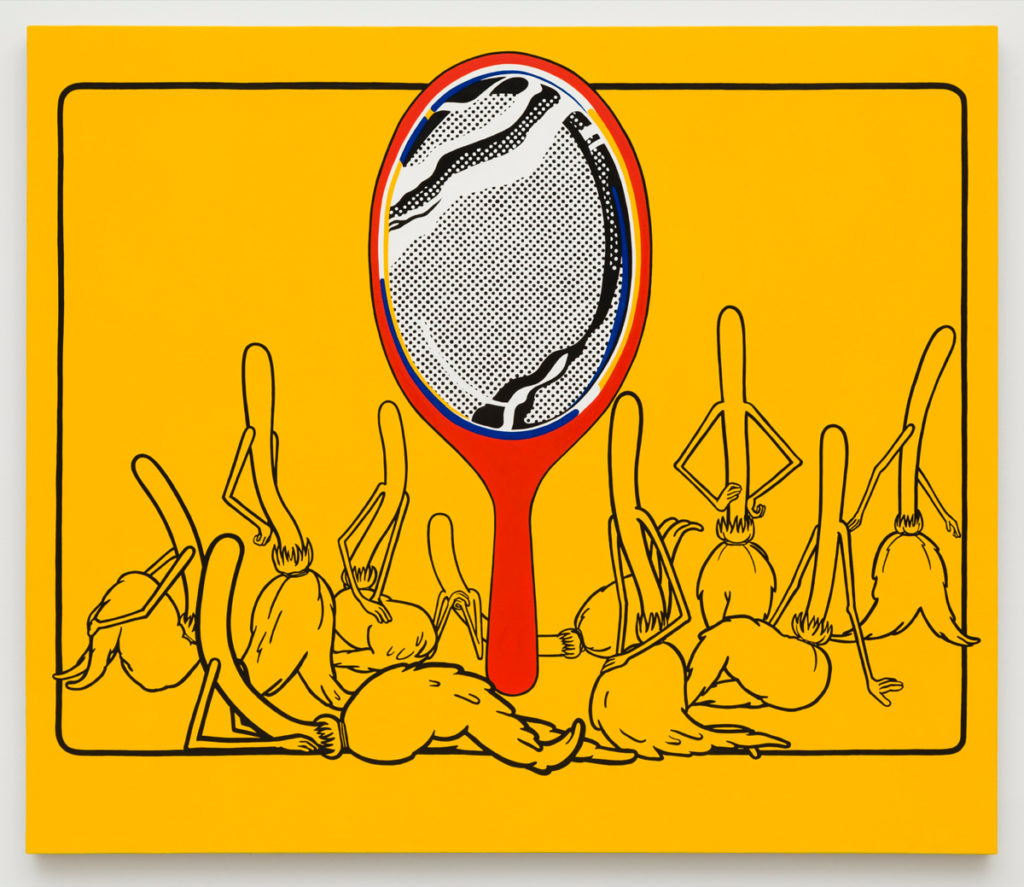

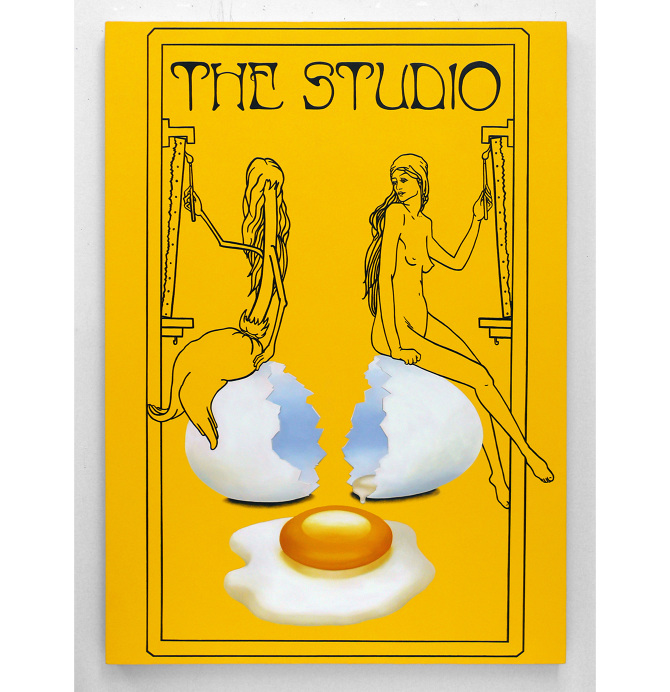

Establishing a foundation of visual signifiers allows us to apply this lens to other objects of contemporary culture, like the art of Emily Mae Smith. Now, the critique of commodification and the performative element as gender as a tool can be easily compared. Smith combines these two main themes within her artwork to create a consistent visual language. Utilizing her own figurative signifiers along with art historical references makes her work pointed, clear, and concise. She uses the medium of oil painting, with all of its historical baggage tied to the language of painting as a practice in itself, to create images reminiscent of cartoons and pop art.3 Both of these images presented are pulled from the body of work called The Studio as it serves as a primary basis for the development of her visual language.

For context: The Studio was an early 20th century Art Nouveau publication of illustration and graphic design. Smith decided that in her body of work she not only wanted to pull from her love of illustration and design history, but directly reference it. Most early 20th century art and publications commodified women to sell products, thus establishing the foundation for gender-based advertising surrounding us now. Another prominent figure in the illustrative/entertainment design field of the 20th century would be, of course, Walt Disney. As is frequently referenced in many contemporary articles, Disney commonly uses female characters in their communicative language of narrative films as symbols of submissiveness, docility, fragility, and other traditionally “feminine” performative traits associated with their ever-famous princesses.4 Smith, however, chooses not to be so blatant to utilize the princesses as symbols. Instead, she focuses on one of the infinite minutiae of feminine performance: domesticity. Avoiding the trite route of representing princesses as white feminist icons (as many of online outlets do, and inevitably feed the commodification of women as tropes), Smith takes the enchanted broom character from Disney’s Fantasia and channels common feminine signifiers including boudoir imagery and traditional sex appeal to contrast with the other signifiers inherent in the broom as an object: dirt and domesticity.

The juxtaposition of the broom as the feminine sex object itself is nothing new or revolutionary; it is an incredibly basic comment stating the obvious: women are commodities, women are treated like sex objects, women are treated like dirt. In terms of communicative symbology, the essential equivalent is a child drawing a picture of two stick figures and saying, “this one is me, and that one is my mom.” However, Smith, in her paintings, delves deeper than that surface reference of simply illustrating the meaning of her symbols on the canvas. Referring back to The Studio, Smith specifically places these broom characters within art history to extend her critique to the Art world. If art is a subset of all language, not just an aesthetic pleasure, then appropriating the image of the Fantasia broom as a sex symbol is not just an image. Using that image within a greater context of art history creates a dialogue.5 The dialogue is more than just the statement that women are objects, like brooms, but that gender has a larger role in art history. Placing a cigarette-smoking anthropomorphic broom on the cover of an issue of The Studio refers to the commodification of women in advertising. Placing many of these brooms around a central altarpiece-like object in her painting The Mirror that directly references the work of Roy Lichtenstein, who famously portrayed the commodification of women within mass produced media, refers back to the importance of women as advertising symbols and sex objects rather than, again, autonomous beings. The critique of women as a commodity is intrinsically linked to the idea of gender being a performance: if we had nothing of value to offer as a product there would be nothing to buy.

In conclusion: using dialogue of imagery and symbol to depict criticism of the treatment of gender inequality within our constructed society is only a critique of a symptom of performative gender. Language beyond nonverbal communication relies on a set of symbols which we develop to convey specific meanings; of course, by constantly reinforcing the contextual meanings of these symbols we continue to box ourselves within the limits of these categorizations and codes. The discourse resulting from the discussion Smith, Butler, and other critics engage in forces us to reconsider these things the same way Warhol wants us to reconsider our dependence on commercialism. What we do to confront these issues, though, is our own decision: in critiquing the treatment of one gender we must appropriate its performance. To exaggerate in order to reclaim is a method of theatricizing what we normally insist is separate from the theatrical; acknowledging that our identities are nothing more than a signifier of our “self” within the greater lens of other people separates imposed codes from our inner identities. To be gendered is a code imposed upon us; to reconstruct our explicit performance as an individual is to control that code and use language to our advantage. Controlling how we perform gender gives us autonomy over ourselves, while controlling how gender is performed through art extends that autonomy to others dictated by the same code.

- Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal, Vol. 40, 4th ed. (1988): 519. ↩

- Karl Marx, “Section I: The Two Factors of a Commodity: Use-Value and Value,” in Capital, Volume I. (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1867), 1. ↩

- Charlotte Jansen, “Emily Mae Smith,” Elephant, no. 26, (2016). ↩

- Buzzfeed, https://www.buzzfeed.com/tag/disney_princesses, i.e.:

Beatriz Serrano, “Here Are All Your Favorite Disney Princesses, Ranked From Least To Most Feminist,” Buzzfeed, last modified March 18, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/beatrizserranomolina/all-your-favorite-disney-princesses-ranked-from-least.

Victoria Sanusi, “This Woman Reimagined Disney Princesses As Badass Feminists And It’s Truly Inspiring” Buzzfeed, last modified March 8, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/victoriasanusi/bad-ass-women-for-roz.

Mariah Oxley, “14 Reasons Why Cruella De Vil Is Secretly A Feminist Hero,” Buzzfeed, last modified April 8, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/mariahoxley/why-cruella-de-vil-is-actually-a-feminist-hero. ↩ - Judith Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion,” in Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives, ed. Anne McClintock, Aamir, Mufti, and Ella Shohat,(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 381–395. ↩

Frances Barker is an artist and experimental musician from southern Maine, who graduated from Maine College of Art in 2018 with a BFA in Painting with a minor in Music. Their work focuses on the space we take up, the greater presence of body, and our (messy) identities. They are an avid conversationalist and always available to reach at www.frncsbrkr.com.