An intro to a serial involving Maine art and: New York art world centrism, geopolitical economy, regional identity, gentrification, and the (d)evolution of the scene.

by Mariah Bergeron

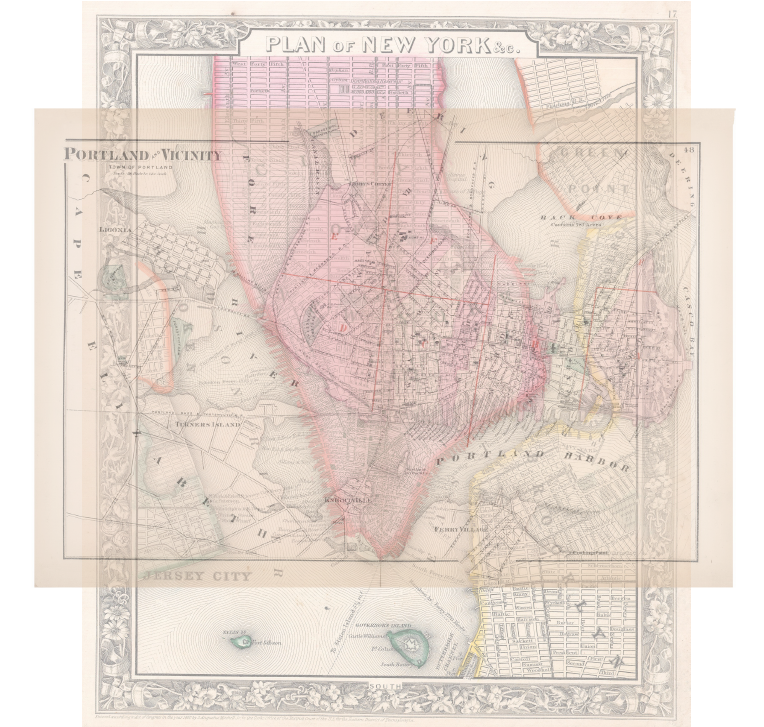

This serial’s intention is to talk about art and Maine and what New York has to do with either. This installment is an introduction to a premise that Maine and New York have had and continue to have a complicated art-based relationship. This involves accepting New York as the current center of the art world (arguable, arguable), specifically due to branding its name beyond its map to denote a certain value, esteem, and credibility.

New York has historically had a resource and outsource relationship with Maine’s oft-painted rugged landscape and people. The legacy of that relationship imprints a sentiment of Maine as more printed postcard than generative and evolving — that there isn’t art being made here. To be from New York is to be already elevated by its very attribution: must have the muster to survive the metropolitan sieve, must be good. Maine has long banked on the specific non-city-ness and seasonal quaintness as an oasis from the grind. But Maine is not merely seasonal, and art economies nationally have set patterns that lately have changed how investors see the value of a place, and it’s very evident in their marketing (e.g. Detroit). Portland, quite specifically, understands how local/art/foodie culture piques an interest that pays. It’s been a boon for the entire state, but artists’ incomes aren’t aligning with the trend.

The fact that Maine contains a truly interesting and exploratory contemporary art scene is real, but it competes with our own tourism marketing agendas of souvenir art of pastoral getaways. Maine is currently caught between the value of our rustic seasonal brochures and the scenester hype constantly compared to and validated by a New York metric. Does The New York Artist, that concept, have a weight to it of preordained acclaim and vaulted status? Does Maine’s value have to exist by that same scale? Do artists bring the cool culture that eventually drives them away? What does it matter where art is made anyway?

I’ll start by acknowledging that this is the first issue of The Chart, an online journal for Maine arts. I think that’s important, and here’s why: art writing is the artist’s champion and combatant. The bothering of viewable art demands conversation and contextualization, argument, debate, questions, confusion. Inaccuracies. The purpose, quality, or validity of art should not be dictated by the gallery, museum, artist, politician, neighbor, or critic. Art relies on its subjective and objective suspension in the entire language-goo of the world. Arts journals highlight “bothering” to give space to art and thoughts outside the piece, which then gives over to discourse further outside those lines and phrases. Scathing, celebratory, or pitifully indifferent, reactions to art, reactions to the absence of art, all signify giving a care.

And it’s really interesting to have a Maine-centric arts journal. Otherwise, let New York be the voice of the American and international palate and pocketbook. Let Maine subsist on seasonal escapism and decorative safety. The world is always happening elsewhere, and there, better.

Maine has long been the summer camp for New York schools of art study: pastoral, rugged, idyllic. Come here, retreat from the art world eye to focus on the craggy beaten rocks, the ernest labor of the fisherman. Recharge and reconnect with the universe, then retreat again. Burst back into the arms of the metropolitan, canvases in hand. Back to a community that understands. That pays.

Meanwhile, Mainers (that elusive title) and transplants have been making art here, new and strange and numerous. We talk about it, amongst ourselves, and mark the flow and ebb of those from away and wonder whether, in our prideful ways, we’re a pressure cooker or a tidepool. We clock the ways that Year-Round-Maine (not summer camp) exists more and more for ourselves, but also in top ten lists and corporate retail and leisure investments. Maine, the commerce politic, has read the statistics, understands both the broken window theory and fallacy. Maine has watched New York make icons of the creative underclasses, and how that built a consumer market for the elite. How various economic fluctuations aid and defeat cultural blooms, affecting real estate markets, crime levels, and business interest. When something’s cool, it’s doomed.

This could be a death knoll for New York, but it isn’t quite yet. Earlier in history, it’s been Paris. Or Florence, or Athens, or Kyoto. I recognize that even now it could be Berlin or Tokyo, you name it. And while I grant New York the center of the current art world, I also recognize that the very idea of centrism gets bemused glances from well-established international art splinter- and anti-centers. New York is comprised of new and old immigrants — the idea of the New Yorker is slippery and New York art by name is a near-impossibility by any maternity test. This crown of centrism is extremely unstable. Paris was dethroned by World War II, New York will be dethroned by the U.S.’s willfully blind war on the classes. But this class warfare exists here in Maine, too. It is even more apparent, especially in Portland, how in this smaller petri dish, we can see how economic plight fostered artist influx. Influx led to cultural intrigue, which has led to corporate investment, higher rents, and whitewashed communities. It’s a pattern. Perhaps we can recognize it and understand how to curb the demise of what we’ve been working to create before we’re too broke to play anymore.

This isn’t about resenting New York for all of the wonderful and hateful things that it brings. It’s about watching and learning the miracles and mistakes, applying them to our own environments and practices, and not merely giving an idle click of the tongue. New York is great. New York is terrible. Both go for Maine, too.

I’m going to leave off with some sagacious discourse from two editors from the wonderful NYC-based Artforum on money and the good work possible in art journals, because it puts the finger on that funny word I’ll be using a lot: value.

Michelle Kuo, current Editor-in-chief of Artforum (2010 to present): And then there is the market: the elephant in the room in any conversation about the situation of media at that time.

Ingrid Sischy, Editor-in-chief of Artforum (1980-88): It very much was the elephant in the room, always. If one looks at a piece like Buchloh’s “Parody and Appropriation in Francis Picabia, Pop, and Sigmar Polke,” one sees how critically important it was to address the subject. Since modernism, it has to be. But it wasn’t stampeding the ideas—the way the market does today, I’m afraid. These ideas concerning the body, the word, the image, were much more powerful than the marketplace back then. We weren’t consumed by thinking about commodification; we were committed to keeping it in sight, though…Now the crisis has to be how criticism, art magazines, any of it, can have any impact on the forces that are at play, since everything is so immediately commodified.” 1

- Artforum, September 2012. http://artforum.com/inprintarchive/id=32030 ↩

Mariah Bergeron lives and works in Portland, Maine.