by Vivian Ewing

In the 1950s, most orchestras were all male. Then the Boston Symphony Orchestra decided to conduct auditions “blind”: musicians would enter the room and play behind a screen so they could be heard but not seen. The orchestra was testing the hypothesis that more female musicians would be hired on their merit alone. But the applicants didn’t only need to be hidden from sight. Women were also asked to remove their shoes. Otherwise, the sound of their heels would give them away as they walked into the room to play the violin, the cello, the flute. Even without sight, bias crept in on the sound of their footsteps.

At the Bowdoin College Museum’s exhibition Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art, curator Ellen Y. Tani, the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, explores how bias creeps into our consciousness via sight and sound. The work in this show addresses what it’s like to possess qualities that so much of the world is not built to serve: blindness and blackness. Second Sight explores these qualities as well as themes of accessibility, race, how our vision shapes our perceptions of the people around us, and what is gained — whether we’re visually impaired or not — when we listen.

Even before the first set of the gallery’s doors are opened, a deep sound emanates from the entrance. When the doors open, the sound is clearer: the minimalist composer Steve Reich’s piece Come Out (1966) loops the words “come out to show them,” which he sampled from the recorded testimony of Daniel Hamm, a member of the so-called Harlem Six. The Harlem Six was a group of young black men falsely accused of murder, beaten by police, and then convicted based on forced confession. In the original recording from 1964, Hamm explains, “I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them,” in order to provide the tantamount visual evidence often required in the criminal justice system. Reich’s piece is an immersive threshold to walk through and a fitting entrée into an exhibition that draws moving connections between sound, race, and identity.

When the second set of double doors is opened, Hamm’s words spill out of the vestibule and into the first gallery. Another perspective on Steve Reich’s audio piece is provided by artist Glenn Ligon, who was directly inspired by Reich’s piece when he created his silk screen painting Come Out #6 (2015). The words of Hamm’s confession are again repeated over and over but this time in black ink on a large-scale white canvas. Where the text overlaps and the black ink accumulates, the words become clearer. Alone on the white background, they are faint — almost indiscernible.

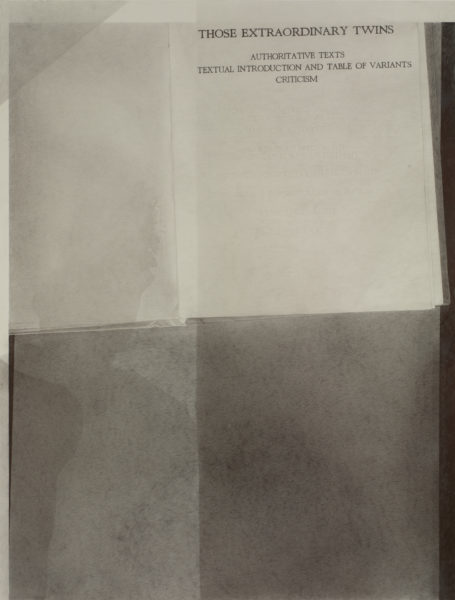

A piece by artist Nyeema Morgan, placed near Ligon’s, is entrancing in its lifelike details. The graphite drawing, Like It Is: Those Extraordinary Twins (2016) is of the title page of “Those Extraordinary Twins” from Mark Twain’s alternatively titled Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894), a book about the ravages of racism on twins in the antebellum South. Both the second title and the author’s names are omitted but creases on the first page and the underlying text of the next page is visible, as is the shadow Morgan’s head would cast over the book when she stood over it. Standing in front of the drawing itself, I checked my shadow against hers.

The often-visceral presence and identity of the artist is important to the meaning of many of the pieces in Second Sight. Tani worked with Bowdoin students to install site-specific wall drawings by Chicago-based artist Tony Lewis, one of which reads “1459 Stand out from the crowd,” — also the work’s title — advice taken from the anecdotal Life’s Little Instruction Book (1991). The question Lewis, who is black, proposes, is whether this advice applies to him. In a video interview with Tani on the college’s website, Lewis says, “When I encountered the book I was confused why the author had some sense of ownership over this language. Basically, it allows him to manifest that authority in a very small, innocuous book that you find in homes all over the world, really.” And later: “There’s a lot of things in that book that my dad tells me to do. And there’s a lot of things in that book that my dad tells me to do the exact opposite. Don’t stand out from the crowd.”

Besides collaborating with students to install Lewis’ work, Tani also paired with the college’s Internet Technology department to create audio “wall labels.” When these hand-held plastic devices are lifted away from the wall, the speaker inside plays detailed information about the corresponding piece that extends beyond what’s found on a typical label, such as visual descriptions. As with many facets of this exhibition, granting attention to the value of hearing and listening provides a different perspective.

In the same room, a giant mechanical music box by Terry Adkins called Off Minor (from Black Beethoven) (2004) sits silent. During a recent visit, a guard came to turn it on for a brief period, kneeling by the piece and scrolling on his phone. The heavy, churning sounds the piece produced were less than sweet. When a couple minutes had passed, the guard switched it off, looked up from the phone and said, “That’s it!”

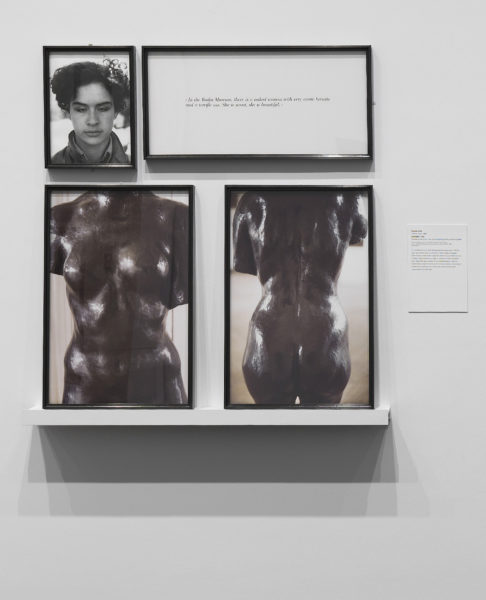

In the next gallery are three pieces by French conceptual artist Sophie Calle from her 1986 series Les Aveugles, (The Blind). The subjects of the pieces — titled The Blind #14 (1986), The Blind, Sheep, Delon, My Mother (1986), and The Blind, My Mourning (1986) — are three blind people of varying ages. In Calle’s quintessential style, the pieces follow a formula: here, a portrait of a blind person, their printed answer to the question of what beauty means to them, and then Calle’s photographic interpretation of their answers.

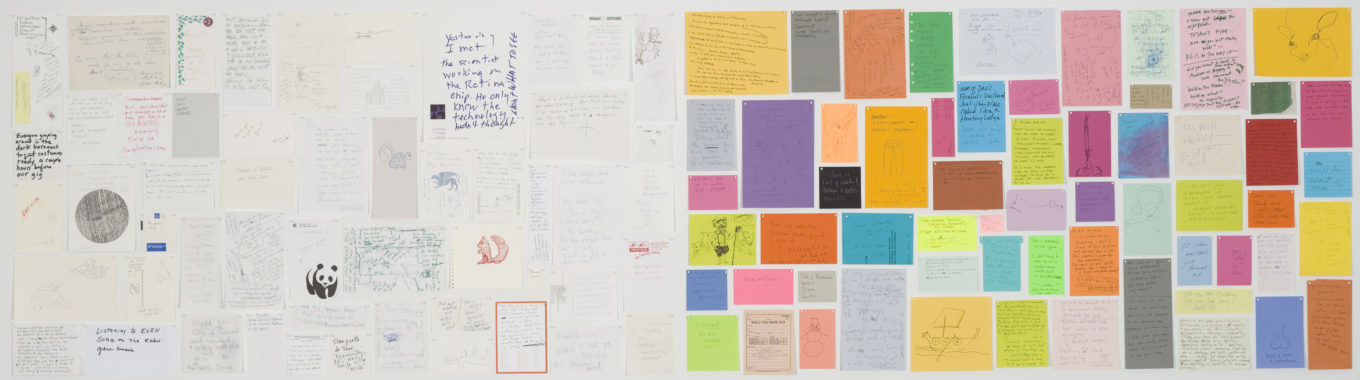

The work is made by a sighted artist for sighted viewers. Joseph Grigely, a deaf artist whose work appears elsewhere in the show, responded to the work’s inherent conflict in a series of postcards to Calle which have been compiled into a slim paperback that sits on a bench by the wall. With or without reading the letters, it’s clear that Calle’s work is othering. Sighted visitors get a voyeuristic glimpse into the mind of the three subjects but the subjects themselves, as well as any visually impaired or blind visitor, get less or nothing at all.

Calle’s work’s place in the show is complex, but that’s why it’s included, Tani explained during a recent phone call. And this inclusion proves valuable: when I first saw the piece I was excited, then taken aback. I realized the initial enjoyment I had was the feeling of experiencing something designed just for me. Part of this show’s strength is in highlighting this experience as a privilege. By deciding to include pieces with a questionable position of author and representation, Tani opens up the potential to discuss their problems in (and contributions to) the larger conversation.

Voyeurism comes up again in two drawings by Shaun Leonardo: Champ (Sonny Liston 1) and Champ (Sonny Liston 2), both 2015. In the first, a section of the famous photograph of the aftereffects of Muhammad Ali’s “phantom punch” is drawn in charcoal. Leonardo has zoomed in to Sonny Liston, lying supine on the ground. In the second, Liston’s body has vaporized and through his smudgy remains, something that was hiding in plain sight becomes clear; the row of onlooking white men with cameras in the original photograph take on a leering quality that’s easy to miss until the two black men are removed.

Furthermore, for the white museum visitor, this row of white viewers behind the boxing ring can act like a sociological mirror. With Liston’s body removed, the white visitor can see a version of themselves staring back and become more clearly aware of their privileged position as onlooker, both inside and outside the museum.

The pair of drawings is surrounded by many other excellent works that deal with racially-fraught issues of perception and perspective. Nearby, a turntable plays the sounds of lilting whistles reminiscent of tropical birds. But the sounds are recordings from YouTube collected and edited by artist Gala Porras-Kim to recreate the communication system developed by the Zapotec people of southwestern-central Mexico while they were under colonial oppression. Porras-Kim created the piece — titled Whistling and Language Transfiguration by “Zapoteco” series (2012) — by tonally matching the sampled whistles to Zapotec spoken narratives she recorded. The quality of the coded calls emanating from the unendingly-spinning record is haunting.

When I moved away from the record, the sound of whistling reached me from another room and again I found myself following a muffled sound to its origin. Behind a heavy curtain is a darkened room where Lorna Simpson’s film Cloudscape (2004) plays, which features Terry Adkins, the artist whose music box is featured earlier in the exhibition, whistling an unidentified tune. He is obscured by smoke, then visible, then obscured again. As he whistles, he seems about to leave us, like the last scene in a film when our hero bids us farewell. His song is cheerful but the look in his eyes says, “I told you so.”

Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art, curated by Ellen Y. Tani, is on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art through June 3, 2018. The exhibition includes works by Terry Adkins, William Anastasi, Robert Barry, Sophie Calle, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Joseph Grigely, Ann Hamilton, Edward Keinholz, Nancy Reddin Keinholz, Shaun Leonardo, Tony Lewis, Glenn Ligon, Abelardo Morell, Nyeema Morgan, Robert Morris, Carmen Papalia, Adam Pendleton, Gala Porras-Kim, Steve Reich, Richard Serra, Lorna Simpson, and Corban Walker.

On May 4, 2018, Carmen Papalia, an internationally known social practice artist, will lead a “Blind Field Shuttle Walk,” an eyes-closed tour of the Bowdoin College quad, offering participants new perspectives on the accessibility of shared spaces. More information about this event can be found here.

Bowdoin Museum College of Art

9400 College Station, Brunswick, Maine | 207-725-3275

Open Tuesday–Saturday 10am–5pm, Thursday 10am–8:30pm, and Sunday 1–5pm. Free.

Vivian Ewing is a writer, editor and reporter. Her work is inspired by the gossip that fuels small towns, the oldest narratives and legends, and the places where these stories intersect. She works at The New York Times.

Vivian is the creator and editor of Enter Rural Scene, an anthology of art and writing by women, trans and queer artists based throughout the country. She was the guest editor of Papersafe Magazine‘s final issue of photography and writing about photography.

Her own writing has appeared in The New York Times, Papersafe Magazine, Wilt Magazine, the Vineyard Gazette, Don/Dean Blog, The Chart and on the walls of Lines of Sight, an exhibition in The Magenta Foundation’s Flash Forward Festival and in Knotweed, an exhibition at Aviary Gallery in Boston.

Vivian was recently awarded a grant from PEN America, a Carlisle Family Scholarship to attend the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley. She has also been awarded a residency and grant at Mary Sky and a grant from the Kindling Fund, as administered by SPACE Gallery. She lives in New York.