a conversation among Myron Beasley, Meghan Brady, Edwige Charlot, Justin Levesque, and Veronica A. Peréz

In early April, five artists, writers, curators, and cultural producers gathered at the Portland Museum of Art to view, together, the 2018 Biennial and discuss the exhibition. Myron Beasley, Meghan Brady, Edwige Charlot, Justin Levesque, and Veronica A. Peréz were convened for this conversation in part due to the diversity in their artistic practices, relationships with institutions, academic histories, and curatorial backgrounds. Mimicking the collaborative nature of the Biennial’s curation, this conversation aims to model the critical potential in slow looking, multiple reads, and shared dialogue. It asks: what is possible when we think with others? What understandings become available to us when we are curious, when we pose questions with sincerity? The conversation that follows is one attempt toward answering, and it has been edited, with the participants, for length and clarity.

Edwige Charlot: I thought it would be interesting to have a conversation around the Biennial, to create a dialogue. Shows have reviews, they get written about, but when does this happen?

Myron Beasley: Well, it also comports with the understanding of the process of the Biennial, these conversations and dialogues.

Meghan Brady: It’s such a treat, really. I find that it’s hard to find time for these kinds of conversations. I think to have a chance to meditate on the show — I feel grateful for that in itself.

Charlot: I also thought that the process that went into the curation — how open and flexible it felt, from what I gathered — that this would be a nice bookend to that. That it can include different viewpoints, lived experiences, different institutional backgrounds and relationships to institutions — none of us have lived the same experiences, so I thought that was valuable as well from that standpoint.

Justin Levesque: Something I experienced throughout the exhibition itself, is this sense of, What is Maine? To some extent, we all kind of know each other, and there’s a risk that we take when we have this conversation. In the exhibition, there’s a kind of quality of mitigated risk, or of trying to be careful.

Charlot: Can you point out a specific work where you feel like that’s there?

Levesque: I’m speaking more in a collective sense as an exhibition that has a kind of carefulness in representation. It seems — in the way I’m tentative about being critical about it — maybe the exhibition is tentative in the way it’s approaching some of the topics.

Beasley: There is also a concern about sincere, robust conversations predicated on understanding what this work is and its possibility. At this moment — and not just here in Maine — that there is a lack of sincere, engaged criticism, without people personalizing what has been written. So notion of lack, or as you say, mitigated risk-taking, I understand. But I want to think about the concept of Maine being small — “we all know each other,” but do we really all know each other? Because I don’t think [Maine is] as small as we want to think it is. I think it’s small because we’re clique-ish. And what does it mean to expand our understanding of not only Maine but its diversity? As we seek to think in terms of pluralities, I think we also reinscribe normality.

Charlot: Normality in what way?

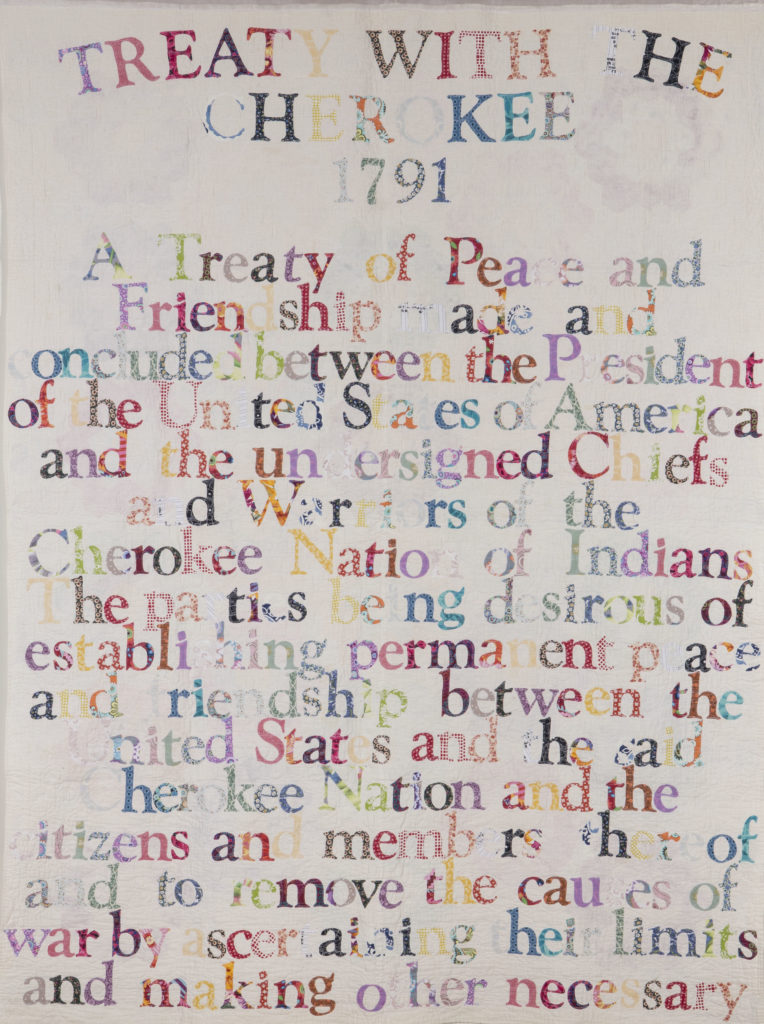

Beasley: For example, we have Native American artists represented, and they are represented in what some would consider “traditional” Native American artistry. We have African American artists, whose subject is about African American lives and experiences. Every African American artists’ subject is not about the African American experience, similarly that of Native American artists. I honor all of that, don’t get me wrong. When we are eager to make diverse representations present we can reinscribe the very thing we seek to dismantle. I am not dismissing the work represented, which is good work! Daniel Minter’s work is fabulous. Gina Adams’ work is amazing to me on another level. Adams use of antique “traditional American” quilts is a subversive performance in form and content. Captured by the aesthetic allure, one reads, and is forced to read, closely to reveal the text as the broken promises of Native American treaties. And then part of criticism is thinking on multiple levels. There’s not just one level of engagement. That’s what I see in interesting ways in this endeavor.

Charlot: But I want to make the distinction that Daniel Minter’s work, specifically, is talking about an African American experience. I think we’re talking about that as opposed to the Black experience in other narratives.

Beasley: Right, right. Absolutely. Minter’s sculptured panoramic stream of painted wood carvings interspersed with scintillating silhouettes tells an Africana story of survival. Witnessing the work of Minter and Adams makes me recall Trouillout’s Silencing the Past. Both artists labor to unravel the bundle of historical narrative to “discover the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others.”

Charlot: Whereas I think Adams’ work feels different to me than Tim Christensen’s or Fred Tomah’s work, because of the content and the methods in which she’s engaging the work — there are different ways of entering. Gina uses traditional methods of presenting quilts to draw you in and then upon looking again you realize it’s not what you thought you were getting into. You can enter through a curiosity about techniques and materials. Her quilts are some of the few works, in comparison to Christensen’s or Tomah’s work, that deliver a reflection of complicity and erasure.

One of the things that I struggled with in the show was, who got an explanatory comma?1 For me, specifically, when I look at Elizabeth Atterbury’s work, I think it can be so easy to dismiss as abstract art in this removed way, where upon investigation when you look at her work, it’s deep. And it is about heritage. So I was trying to make little corners and relationships between the work: she is bookended by Tim Christensen and Fred Tomah and I was like, this is the heritage corner! You know what I mean? With these pieces in conversation, the description could have supported more of what I think some of the intentions were around this show, or my assumptions about them.

Levesque: Rosamund Purcell’s write-ups were super long! There’s a lot going on there. It sort of put a hierarchical lens on how the institution was viewing or thinking of the work and its relevance in the exhibition. Which, to me, I don’t know — is it weird to get obsessed with museum labels?

Beasley: But labels are so important! In my curating class, we spend two weeks on label writing because they’re really powerful in the ways in which they define, characterize, identify work. Labels are powerful and important.

Brady: When you go to a big show at the Met, there are more people gathered around the wall text at the introduction to the show than the actual work. It’s a way for people to really feel, in some ways I imagine, to feel comfortable with the work. Or to feel comfortable enough to start to take it in.

Beasley: You know I have to say, I’ve attended several of these Biennials and this is one of the least populated. Usually so much is crammed into that space and it can be overwhelming and not conducive to true engagement in the art. I appreciate that it’s not overdone this year. And I appreciate — you know you’re talking about the “heritage corner” — there’s something about the performance that’s happening from Adams’ quilts from—

Charlot: —the canoe?

Beasley: Thank you, and leading up to Minter’s work against the wall, I think there’s just this beautiful performance that flows there, and I’m in awe of the curatorial choice. I felt like the design of it flows beautifully.

Brady: I couldn’t help but think there was something being suggested by the curation when you’re sort of asked to turn your back to Stephen Benenson’s paintings to take in the central part of the gallery and then look towards the David Moses Bridges and Steve Cayard canoe, flanked by Gina Adams and the sort of gesture of the Minter piece on the wall — it was a powerful moment. It felt like, just for a moment, turn your back on painting and look towards this alternative, as a kind of revision. And there’s another moment as you exit the gallery when you wind by Elizabeth Atterbury, by Fred Tomah’s pieces, and finally Elise Ansel’s paintings — for me it’s a conflicted final act to the show, the combination of traditional basket under glass and the sort of rethinking and reframing of Western painting and the narrative by Ansel.

Levesque: What complicates that experience, too, are Shaun Leonardo’s drawings. There are these formalist things happening in that area of the gallery, but then you also have this sort of digital-meets-drawing situation, and the subject matter is tragic and unsettling. Leaving on that note is a reminder in the midst of more classical or traditional approaches to making that is complicated or—

Charlot: But isn’t that tension in an institution? That there is this tension between this conversation between “here are the things that are based in an academic, historical context,” and “this is what we know of ‘art’,” right? And there’s this reality of that content and our consumption of that content. And this is where they actually meet and we have to exit through them. I didn’t feel like I needed to make a choice, it was just about leaving that space through those parallel conversations.

Beasley: That’s where understanding or engaging begins, in the in-between spaces, the rubbing against, the discomfort.

Veronica A. Peréz: The paintings and the Leonardo drawings seem to be about engaging in those difficult questions. If we can’t start to ask them, then how are we actually going to be able to have an answer? I kind of felt ambiguous leaving that space, but at the same time a little hopeful that maybe people are starting to take notice.

Levesque: What I loved about those drawings, too, is that I was looking at the quality of mark-making and seeing that digital reference, and I think I actually spent more time with those pieces when I first viewed [the show] than anything else. I was perplexed and intrigued by how those two things came together, and the choice to represent the screen this way. It connected me so much to Erin Johnson’s piece, in the way the image is a truth-telling device or not a truth-telling device, and how the media image permeates collective consciousness, how we remember things. I watched the video that Erin Johnson made, and the people who are telling that story seem almost like they were changing their own memory of [the (fictitious) nuclear strike] happening—

Beasley: Absolutely!

Levesque: And I feel like there’s almost that same quality in Leonardo’s drawings, too. Those pieces really connected for me — it just happened today [upon second look], not prior.

Charlot: I didn’t have the same reaction to Shaun Leonardo’s work. I mean, it’s funny, the two Shaun/Séans in the show were the two moments that I cried when I first saw the show. Séan Alonzo Harris’ work because, like, besides the Gordon Parks show that I had seen as a young child — images of Black boys: not men, Black boys — I rarely encounter that in these kinds of walls. And to see them at that scale…I mean I knew what the drawings were because that video [of Laquan McDonald] is burnt into my memory. So just being a person of color and coming to the space with that, I just think that my walking through the exhibition will be different because of who I am in this world. So that is a particular experience, right? That is a set of lenses. The show feels like a snow globe of all of these conversations that are happening: climate change, womanism, feminism, tradition, cultural erasure, oppression, police brutality…for once I felt like we’re not just doing a show about this one thing. It felt relevant, like such a nice way of capturing what is happening in this moment, which is a confluence of all these things being talked about. And that felt meaningful.

Beasley: Absolutely, absolutely. Hans Obrist, in a conversation about curating, likens it to a bridge, and one of these bridges is the local, which is always supposed to meet with the global.2 I see such a convergence prominently here, right? It’s great. I totally see that.

Charlot: I think it goes back to your point, Justin, about regionalism, and this conversation about who is here in Maine.

Levesque: Well, it’s kind of funny, I was thinking there are all these issues sort of popping up, and to some extent then I was thinking it also reminded me of my Facebook feed.

Beasley: Ah!

Levesque: It’s like, I’m being hit with all of these things; maybe we don’t pay attention to them after a while. Coming back to your point about reinscription, Facebook does that as well, with climate change, or with whatever.

Beasley: The numbness.

Levesque: Exactly. So then, is there a kind of social feed influence or feedback loop that’s happening in the way that we interact with pieces or the way we interact with issues through devices?

Charlot: But doesn’t this sort of talk about why it’s of value? I think that’s what’s valuable is it’s actually presenting what is. I feel like a lot of the time there are curatorial filters and blinders that are like, “Let’s make it nice and neat and digestible.” Where I love the fact that this show is a monster that is not digestible.

Beasley: Yeah. The other part of that bridge metaphor that [Obrist] uses is that also the bridge can be rocky. And curating can be dangerous. Or should be dangerous.

Charlot: Mmm!

Beasley: So it should encourage the susception of discomfort. And part of that is it’s not about “good.” This show is a perfect example of post-modernism’s concept of fragmentation. In the sense that, yeah, it is a Biennial, it is a show, but it’s fragmented. Which can be discombobulating for some people. But that’s what it’s all about: to jar, and to make people think and ponder, and to wrestle, right? In that regard, it is dangerous.

Peréz: I remember the first time seeing the show I was so inundated with all of these messages; it was really hard to wrap my mind around it. But within all that confusion, there becomes a clarity. You start to see change, you start to see what can be, and then you know kind of where you need to start and where you need to go. Change isn’t going to happen overnight, these things are going to take time — and I’m speaking to all themes present in the show. For me personally, work that doesn’t engage with a dialogue with something that’s happening [in the world] is really hard for me to hold onto. I think that being artists and being able to have these difficult conversations is a gift that we’re allowed to have. And it’s about viewers in the public, or whomever is viewing the work, asking questions: what is this, or what does this mean? Sometimes shows like this are very overwhelming and two sides emerge: they make people either really fearful or they makes people think, “Yes, we’re gonna try to answer these questions and try and do this.”

Charlot: I think I would push back a little bit. I hate that this show keeps being referred to as “diverse,” because to your point, this is the norm everywhere else.

Peréz: This is nothing new for Philadelphia or New York or any place like that.

Charlot: Right. That’s the thing that I keep wrestling with. This show is interesting to me because it gets away from the prim and proper ways that we view works within this institution.

Levesque: To some extent, I think it’s all done in the safest way possible.

Beasley: To go back to the tentativeness you mentioned earlier.

Charlot: Where are those things pushed? And where is the danger in the curatorial process? It’s radical and safe.

And I’m going to use your Facebook comment because, like, everyone gets to opt-in to the conversations that are happening in some of the works. With Anne Buckwalter’s work, if I don’t want to engage with it, I can walk away and go look at Stephen’s paintings. And formally, there are different color relationships, it’s a different scale… I keep going back to this idea that there’s a level of risk, but it’s very low risk. It’s like a yellow/green. We haven’t even tipped into warning yellow. And so I keep thinking about how this is an opt-in [show], an optional thing that once you’ve taken a look you can kind of check a box. And so once the show comes down, then what happens to the conversations?

Peréz: Well, you were talking about engaging the community. It shouldn’t just stop here.

Levesque: Once in a while something does actually engage you to the point where you want to know more, and then you click through. So maybe that’s what the show is doing to some extent: it’s hitting you with these things and then hopefully you’re going to be able to click through on what you’re resonating with, or what speaks to you and then there’s an engagement beyond the show.

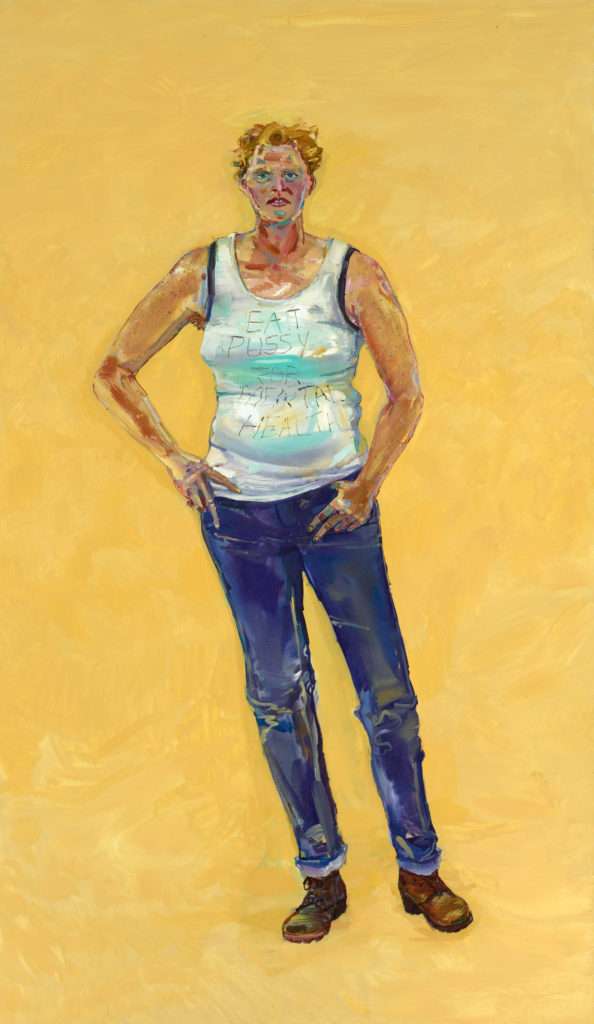

Charlot: But that’s my comment about the opting in. What this show provides is an opt-in feature, and I think there’s such possibility and potential just in that. Someone may come to the museum thinking they’re going to see some wonderful maritime landscape painting, and the first thing they see are these gorgeous portraits [by Angela Dufresne] of these two women just by walking by. I think Jenny McGee’s piece is a nice way to draw people in. There’s an interesting relationship between her work and Jonathan Mess’ work, actually. And I kept trying to find these relationships.

Levesque: Jenny’s piece is actually one of the hardest for me in the whole show because it felt like the package or the plastic that’s wrapping the gift.

Brady: It was more topical than her other work?

Levesque: I feel like she was underserved. Her piece wasn’t allowed to relate to what was inside because of the barrier of the wall.

Charlot: Yeah, but think about the actual physical structure of the museum: that wall, you can see it from all the other floors. And I’m thinking about how are you going to lead people in? It’s a nice lead-in, because it’s like, “Oh, shapes! Abstraction!” It’s very similar to my comment about Elizabeth’s work — I mean that it’s possible to walk away by dismiss it as “abstract art.”

Levesque: But I think her work is more than that, too—

Charlot: Yes, but I’m saying that particularly to this audience, I think it’s an awesome lead. Jenny’s work is heavily influenced by her landscape and public. I do agree with you that I wish that she was physically within the other shared space.

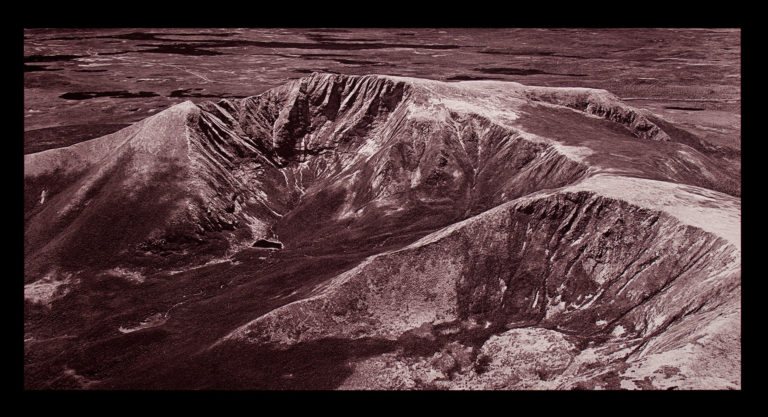

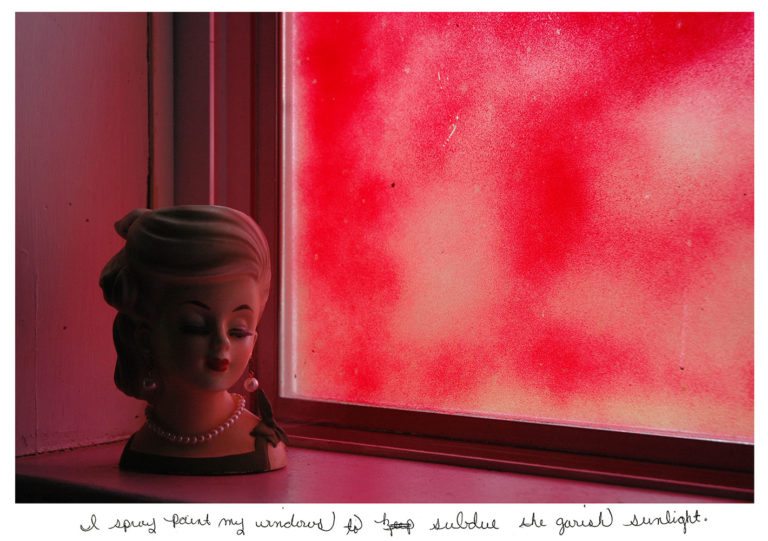

Levesque: So John Harlow’s work were images that I was having a difficult time making some connections with. I think that his work did the same thing that [Johnson’s] piece did in a way: you have the straight photo/documentarian kind of truth image, but then the way in which [Harlow’s] images are then modified — the inscription — is really nice. His work also has this question around the representation of a Maine vernacular: what is a Mainer, especially in this tradition of documentary photography or image-making? It can be hard, I think, engaging with the history of images that exists around this topic.

Brady: There’s a discomfort for me in viewing the Harlows. People who have cameras are in a position of power capturing their subjects. And so I felt voyeuristic. But alternatively, I was grateful for the subject’s handwriting on it, almost as a drawing, and as a kind of empowerment or agency over the photo of her and a way to own world that she so generously exposed for us all to see.

Peréz: Yeah, there was no disconnect between subject and photographer. They worked in tandem together. There was a connection for me between the image and the writing.

Levesque: The most interesting thing about them is the exchange between the photographer and what’s being photographed. And how there’s a sense of reflexiveness that’s happening. It also seems like there’s a very unique moment in the show — I felt like the regionalism or the “portrait of a Mainer” crystallized in a different way than some of the other works.

Peréz: I guess I don’t understand what you mean. Maybe because I’m a Maine transplant: I can’t call myself a Mainer because I’m from New Jersey.

Charlot: Do you mean like the mainstream [understanding]? When we talk about “Mainers,” it’s usually a white person who’s working class in a rural Maine setting.

Levesque: That’s exactly what I mean. And how that kind of image mirrors a bigger conversation that’s happening on a national scale.

Charlot: I have to say that I was really excited to see folks that were born after 1985 in a show! Together! The fact that someone (Harlow) was born in 1989 that’s in a show in a museum felt really refreshing. I’m going to make an assumption and say that Anne Buckwalter is 30, 31? I do remember in the conversation that the curators had had publicly around their hope to include artists, they talked about how they wanted the inclusion of these artists to be a next step in their trajectory. And that felt really generous to leverage the power and the prestige and the influence of the institution to actually work for an artist, right? It felt good to hear about that mindfulness and that thoughtfulness around a mechanism that creates opportunities for folks. That this could be a pathway for artists.

Levesque: It means you have access to that pathway.

Charlot: And don’t get me wrong, I love David Driskell’s work, but this is where I felt power and influence. When we talk about places where I wasn’t really engaged, I know his work, I like his work, it’s important to me, but it didn’t feel relevant.

Beasley: Well he’s the only artist in the show that the museum has collected. I love him as well, but I was jarred that he was in the show. That would be a good question, you know?

Brady: Maybe he’s supposed to represent the end that’s made it, that has been absorbed by the institution. You know, he’s crossed the other side.

Beasley: Well he is an institution! I mean, he is! He has an institute named after him!

Levesque: It’s a little of a nod to the old guard. I felt like the placement in the space, it felt like a little hand-off to the platform.

Beasley: There’s one other thing that I have to think about in the show: the homage to the artifact—

Charlot: Yes!

Beasley: Because you know, I teach material culture, and it’s so important to see! Oh my goodness! Objects have a life! They have a life of their own, and we see objects and recycled things used in such amazing ways in this show.

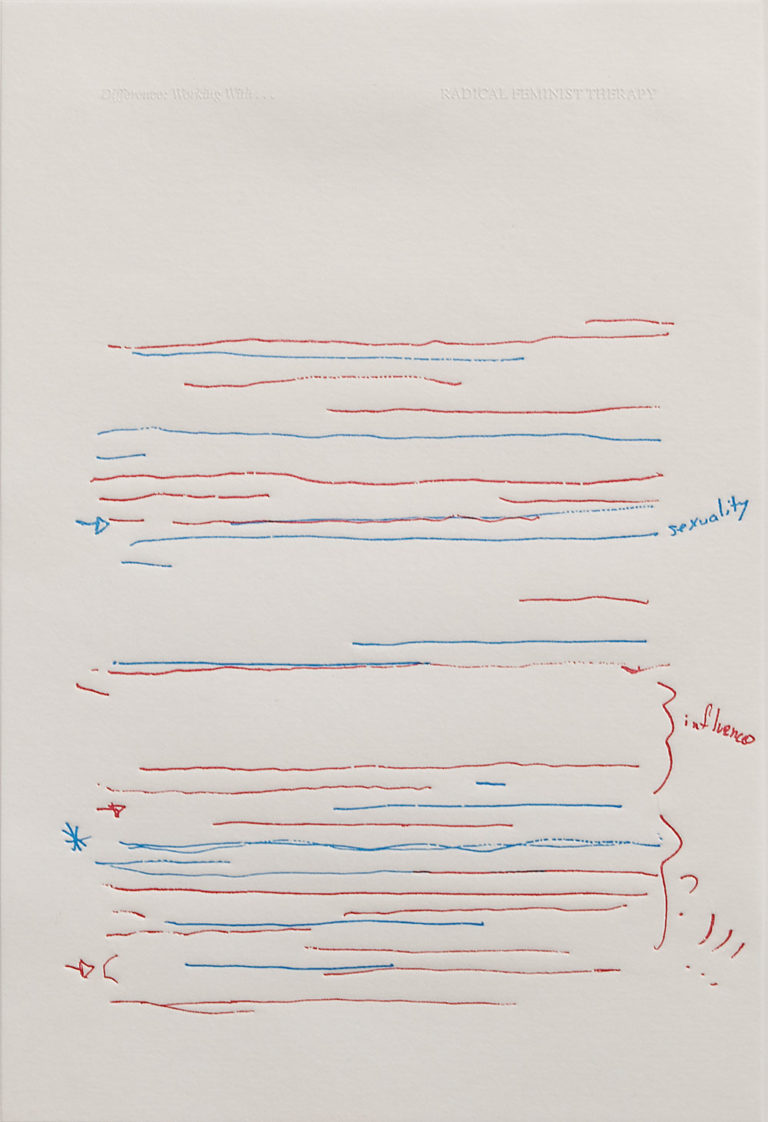

Levesque: So how do you see the material culture related to Becca Albee’s work? I thought her work next to Rosamund Purcell’s work was kind of an interesting way to— there’s a history element that’s happening in both. I mean, I actually had a hard time with the sort of “Smithsonian” aspects of Purcell’s work, but to some extent having it close to Albee’s work changed it for me.

Beasley: Oh, how so? Did you feel like the set-up of these objects were too removed? Scientific? Classically-arranged?

Levesque: Yeah, I felt like it was in a place between what is a Smithsonian kind of object and something that’s more speculative or interpretive. What I liked about it was this expansive history of one time, across the layers of that wall. But then with Albee’s work, you’re seeing a sort of compressed view of history. And so I think those two worked well in terms of record-keeping or time, or—

Beasley: Documentation.

Charlot: Yeah, I read it as revisiting and collection. Taking notes and collecting feel like the same mechanism, right, the same method of working. And what I liked between the two of them was the choice of presentation and display was so different.

Peréz: I didn’t even think about Purcell’s work being next to Albee’s work until you said it: it’s about revisiting these two tumultuous times in American history, in which Albee’s dealing with feminism twenty years earlier, Purcell is dealing with World War I. And seeing these things however many years later, there’s still this tension that exists. In the catalogue, Nat May says, regarding Becca Albee’s piece, “It might be easier for more people to be involved in this conversation now than twenty years ago.” And I feel that it takes time to dissect these difficult conversations to be able to look at them in new ways.

Beasley: And they’re traces of an archive.

Brady: So what else about material culture?

Beasley: We have Tomah’s baskets, we have Adams’ quilts. They are remade, redone, reused. And, you know, the calico set, the rewriting, layers of writing. Minter’s piece is found collections, I mean, the cans at the top, right? So that’s what I mean by there’s an amazing use of objects in the show, in a profound way.

Peréz: I’m really glad you brought up material culture, because I think it’s important. I’m a sculptor, so obviously all my work is material, and seeing that different materials — like this little water bottle, for example — could have different meaning to Meghan, could have different meaning to me. You know, [materiality] has all of these different crossovers and beginning to be able to see what Minter is talking about his work, in expanding the notion of the broom, or the can, or—

Beasley: Right!

Peréz: Or the rock and the lock. Being able to dissect all of those in the lens and the frame that he’s given is important to not see these materials as, “Oh I already know what that is. I already know what that piece of wood is. I already know what that broom is.” It’s like, well, no, you really don’t because your history is different from Minter’s history, my history, and so on.

Beasley: Absolutely. And let’s not forget that in Mess’ [ceramic] work, the reusing of found materials, you know? That’s amazing and beautiful to see.

Peréz: The reuse and the forgotten is as important as the new. All of the materials used by Minter have connections and connotations to his personal history. But they also have history to you, too, and it’s about turning your lens to see through the eyes of someone else. I also wanted to speak about Mess’ work and how these forgotten materials become so full of life and so tangible when they could have just been thrown in the trash. But this is only found through reading deeper about the work.

Charlot: Yeah, but that’s what I like so much about some of the video pieces — like Nancy Andrews’ piece, right? I needed to know the experience in order to have a pathway to the work.

Beasley: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Charlot: There are just so many layers. I was like, “Am I going to get something else out of going again?” And you know, this is my third time through, and now I think the fourth time is going to be like a completely different experience. And it feels important in that way. I think you talked about, will this have longevity? I think so.

Peréz: I agree with you on that. With work that speaks to contemporary tensions, is it effective and does it have longevity? With Becca Albee’s piece, you start to see the changes over the years: this is where we started [with feminism] and this is where we’re going and where we’re at now, being able to see the history of everything we went through. Even in Minter’s piece, it’s the same thing.

Levesque: Well, what’s interesting to me is the show is doing two things at once. So how is this show, or why is this show, why is it able to hit both of those notes (of longevity and contemporaneity)?

Beasley: We should always look at things on multiple levels. It’s not a conflict. I think this is part of the dialogic tensions that are ongoing. If I can go theory again just one more time, you know, Derrida says, about this notion of hauntology, that these works of art will haunt you — and that performances never end. Creative work will haunt you until you’re able to engage with it at some point. It is a reoccurring experience that happens with us, that, we may not get it today, it may seem conflictual, and it should. It should allow you to think about the creative experience on many different levels: the aesthetic level, technique level, the political — as in capital P — level, gender, sexuality, all of those multiple subjectivities that we engage with. And not privilege one over the other. Because they’re always working; we should always acknowledge these levels simultaneously. So I get tension.

Levesque: And I really want to point out that I think that’s one of the successes of the show.

Beasley: Right. It will continue to haunt people. And they may not get it, they may not understand it. I believe that.

Levesque: Does anyone have any last words?

Beasley: Any last words? I think it’s a great show. You know, I appreciate the show on a number of levels. I love that, as I mentioned, the objects have a huge life in this show. I appreciate the multiple dialogues that exist, that are encouraged from viewing this show. It’s one narrative, it’s not one story.

Charlot: I’m just grateful that it’s a place for us. The first thing that I wrote was “for us, by us.” It just feels like a show that is actually for us, do you know what I mean?

Beasley: That’s good, that’s a huge statement. Did you feel that way, Meghan?

Brady: Yeah, I totally felt that way. I’m also, I’m responding still to what you said just a couple minutes ago, in that you feel like you can go back and go deeper and deeper with the work. By seeing this show, I feel heartened by what Nat is claiming as the art community. I feel optimistic, and in that way, it feels really good. Maybe the institution’s a little more complicated!

Beasley: They all are.

Peréz: You know, this show just made me feel included. It made me feel like I can keep making work, because for a while there, I didn’t make work for two years because I was told, “Your story doesn’t matter, your materials don’t matter, your materials have no meaning,” and being told that as an artist, you’re just like, well, then, why am I making anything? So being able to come into this show specifically and be confronted immediately with Dufresne’s portraits is really impactful and really powerful. Being able to see others in a museum, to see yourself in a museum, is really powerful.

The 2018 Portland Museum of Art Biennial is on view through June 3, 2018. The show was curated by Nat May, with assistance from Theresa Secord, artist, educator, and founder of the Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance; Sarah Workneh, Co-Director of Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture; and Mark Bessire, the Judy and Leonard Lauder Director of the Portland Museum of Art.

The artists in the 2018 Biennial are Gina Adams, Becca Albee, Nancy Andrews, Elise Ansel, Elizabeth Atterbury, Stephen Benenson, Sascha Braunig, Anne Buckwalter, Steve Cayard and David Moses Bridges, Tim Christensen, Jenny McGee Dougherty, Angela Dufresne, David Driskell, John Harlow, Séan Alonzo Harris, Erin Johnson, Shaun Leonardo, Jonathan Mess, Daniel Minter, Rosamond Purcell, Joshua Reiman and Eric Weeks, Fred Tomah, and DM Witman.

Portland Museum of Art

7 Congress Square Portland, Maine 04101 | 207.775.6148

info@portlandmuseum.org

Winter Hours (through May 22): Saturday and Sunday: 10am–6pm, Thursday and Friday: 10am–8pm, Wednesday: 10am–6pm.

Adults: $15, seniors: $13, students with valid i.d.: $10, everyone age 21 and under is free. The PMA is free on Friday evenings from 4pm to 8pm and free for members.

Myron M. Beasley, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in the areas of Cultural Studies, African American Studies, and Women and Gender studies at Bates College, USA His ethnographic research includes exploring the intersection of cultural politics and art and social change, as he believes in the power of artists and recognize them as cultural workers. He has conducted fieldwork in Morocco, Brazil, the US and currently in Haiti. The Andy Warhol Foundation, the Whiting Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities and most recently the Reed Foundation (The Ruth Landes Award), have awarded him fellowships and grants for his ethnographic writing about art and cultural engagement. He has also been recognized for his teaching (awarded teaching awards) and work in the area of pedagogy from the International Communication Association, Ohio University, and Brown University. His writing has appeared in many academic journals including The Journal of Poverty (which he served as guest editor for a special issue on the topic of Art and Social Policy), Text and Performance Quarterly, Museum & Social Issues, The Journal of Curatorial Studies, Gastronomica, ELSE and Performance Research. He is also an international curator.

Meghan Brady is a painter who lives and works in midcoast Maine. Using painting, printmaking, drawing, and ceramics, Brady explores the limitless possibilities of an open process, including elements of the human form and abstraction. Brady shows with Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects in NYC, ICON Contemporary Gallery in Brunswick, Maine, and Perimeter Gallery in Belfast, Maine. She has been included in exhibitions at the Portland Museum of Art and CMCA. She is currently the artist-in-residence at Tiger Strikes Asteroid in Brooklyn, NY. Brady is a graduate of Smith College and Boston University’s MFA program in Painting.

Born and raised in Paris, France of Haitian heritage, Edwige Charlot emigrated to the United States at the age of 9. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts in printmaking with honors from the Maine College of Art. Her work has been exhibited in New England, Oregon, New Jersey, and New York. Edwige was awarded the St. Botolph Club Foundation Emerging Artist award in 2013 and a Maine Arts Commission Good Idea Grant in 2011. Edwige has participated in exhibitions that explored issues of race, migration, heritage, and identity, including The Other Side of Shade (2013) and Undoing Racism in the Joanne Waxman Library at the Maine College of Art (2009). In addition to her art practice, she is currently an advisor to the People of Color Fund at the Maine Community Foundation and runs a strategy and design consultancy, Creative Approach co. She lives in Portland, ME, with her husband and son.

Justin Levesque is an interdisciplinary artist living and working in Portland, Maine. He received his BFA in Photography from the University of Southern Maine in 2010. Levesque is a Maine Arts Commission Artist Project Grant recipient (2015, 2017), and in 2015, was selected as one of thirteen emerging photographers under 30 in Maine by Maine Media Workshops + College’s PhoPa Gallery. Levesque has exhibited throughout New England and nationally at Midwest Center for Photography in Wichita, KS; Terrault Contemporary in Baltimore, MD; and JanKossen Contemporary in New York City. In 2015, he created an independent artist residency aboard an Eimskip container ship sailing from Maine to Iceland. In 2016 Levesque then installed a public art intervention in a shipping container about his residency with support from The Kindling Fund, an Andy Warhol Regional Regranting Program administered by Space Gallery. In response to his work about Maine’s emerging relationship to the North Atlantic and Arctic, he was invited to be a fellow of The Arctic Circle artist residency in Svalbard, just 10 degrees from the North Pole, in June 2017.

Veronica A. Peréz is an artist whose work primarily focuses on using sculpture as a tool from which to empower people by means of exercising radical empathy. Peréz uses sculpture as a means to create intense personal moments that critically contest narratives of identity by means of hybridization, alongside ideal of beauty and nostalgia. Fragility echoes sentiments of a lost self and at the same time, parallels contemporary feminist tensions. Peréz has a BFA from Moore College of Art and Design and a Masters in Fine Arts from Maine College of Art and she is currently working in Westbrook, ME. Her most recent solo exhibition untitled, was at Kingston Gallery in Boston, ME. Currently, she teaches at Southern Maine Community College in the Sculpture Dept. and Bomb Diggity Arts in Portland, ME. She is also a current artist-in-residence in Rockland, Maine through the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation.

- Charlot is referring to the wall text, or chats, that describe a work of art in a museum or institution. The phrase explanatory comma specifically refers to implications of race. ↩

- “The twenty-first-century curator is a catalyst — a bridge between the local and the global. A bridge has two points, two ends. This is a metaphor for how one crosses the border of self. One position, that of the original personality, will always be more stable, but the other, which is floating, is less stable; therefore the bridge can be dangerous.” Obrist, Hans Ulrich, and Carolee Thea. “Foreword.” On Curating: Interviews with Ten International Curators, edited by Thomas Micchelli, D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2010, pp. 120. ↩

myronbeasley.com | meghanbrady.com | edwigecharlot.com | onedynamicsystem.com | veronicaaperez.com