by Julie Poitras Santos

[preamble]

In the late 1550s, Pedro de Hoyo, head of the authority servicing royal residences in Spain, wrote to King Philip II expressing enthusiasm about a young boy who was able to see water under the earth. This boy was the best zahorí de Hoyo had yet employed, and certainly would find much needed water resources.1 Peculiar to the Iberian Peninsula, zahorí is a Spanish term from the Arabic meaning a person who brings to light what is hidden in the earth. Containing the same root as the mystical Hebrew treatise, Zohar, this “bringing things to light” and the ability to detect what is hidden in some transcendental manner became assimilated to other seers and other kinds of seeing, other forms of illumination.2

[amble]

Katarina Weslien and I were drawn together by our interest in walking as practice: aesthetics, endurance, lifestyle, immersion. And she recently led a foraging walk, mycophilic/mycophobic, in a project I curated. Weslien, like the zahorí in 16c Spain, is interested in seeing what lies beneath the surface, in how we might use new forms of investigation as means to uncover hidden things and how we bring them to light. In the foraging walk, for example, we learned how mycelium grows as a subtly extending meshwork beneath the ground and we followed the preferred conditions of these invisible threads to discover well-hidden chanterelles.

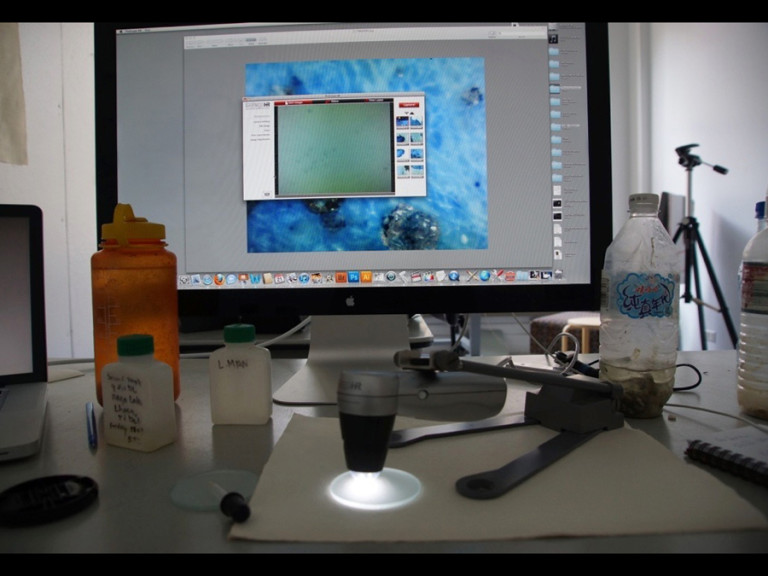

During the course of our studio visit3, Weslien listed other ways of seeing under the surface of things and challenging our perceptions, methods she uses in her own work. From slowing down a video to 24 frames per second to pick up subtleties in movement, to going in close with a microscope, she breaks her materials down into components, dissects and re-views them. And in so doing, she illuminates other worlds.

Weslien’s work is tied up with her years of travel. Decades ago, as a volunteer for the United Nations Development Program from 1976–78, she lived and walked with Kurdish nomads on the border of Iran and Iraq during their spring migration. During that same time period, she also crossed over land through Afghanistan and Pakistan into India.4 Later, in 1984, she walked to Muktinath in Nepal, a site sacred to both Buddhists and Hindus at 12,172 feet in the Himalayas. Considered the only place on earth where you will find all five elements — fire, water, earth, air, sky — that make up all material things in the universe according to Buddhism and Hinduism, devout pilgrims journey on foot to Muktinath from as far away as southern India to bathe in the sacred water that flows from 108 boar-headed fountains.5

This was Weslien’s first encounter with Hindu pilgrims. She has returned to this part of the world — Nepal, India, Tibet — almost yearly ever since — she can’t remember how many times she’s been — and pursues a deep and abiding interest in how we make meaning, and in investigating social and spiritual systems that seek “getting to some truth.”

[locate]

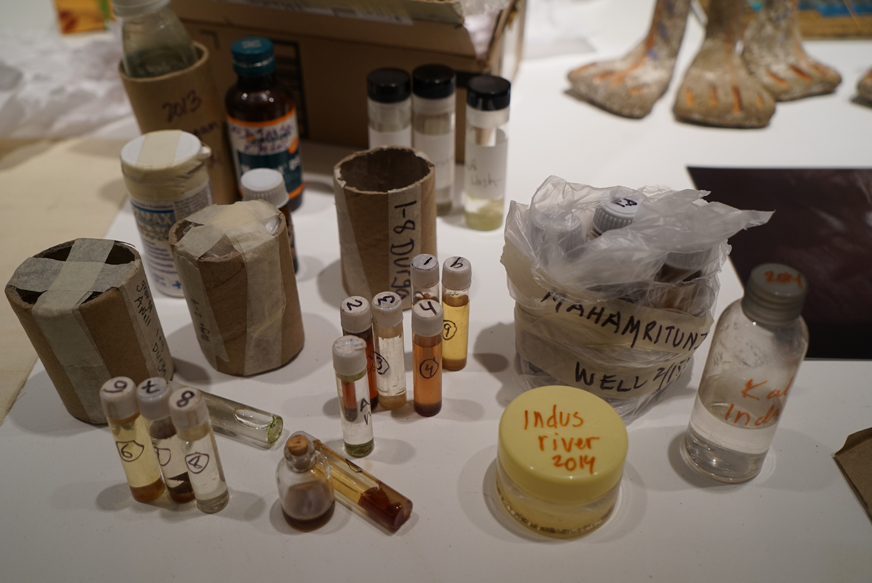

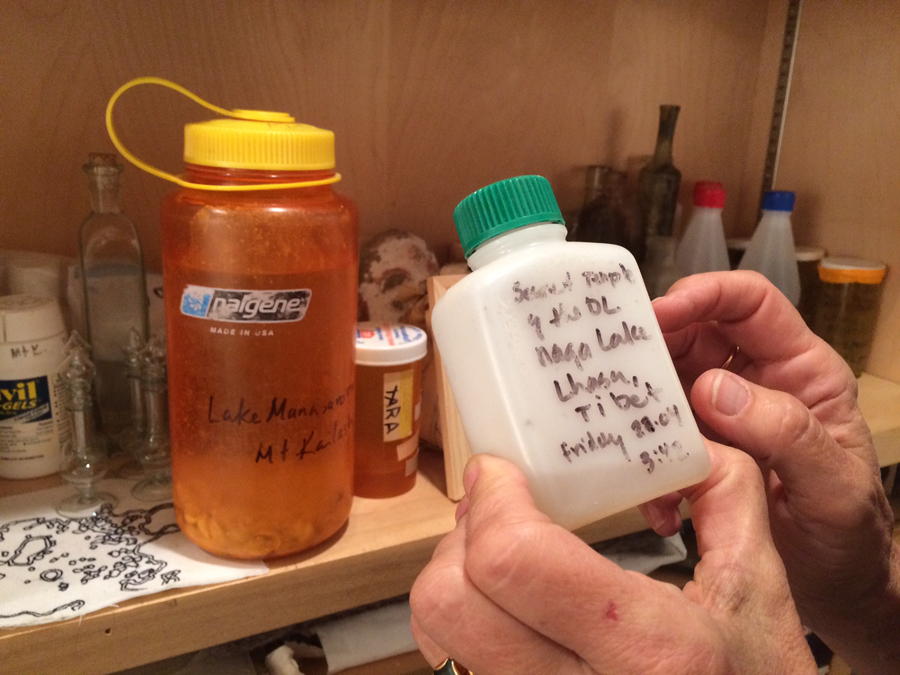

On shelves at the side of Weslien’s studio I notice a hodge-podge fleet of small receptacles — travel shampoo containers, Tylenol containers, drinking water bottles with Chinese writing, tiny glass vials, some decorative glass perfume jars, jam jars, vinegar jars, medicine bottles, Nalgene water bottles, and plastic travel containers for cream. Some of the containers are wrapped protectively in toilet paper tubes, all are labeled, coded in numbers and names: Mahamrityunjaya well, 1–8 Durga, Indus, 6, 7, 8; 1, 2, 5; Naga Lake, Monaserova, 9, Tara, El Yunque stream.

It is almost a truism that things at the edges of the studio are what attract the eye of the visitor; inventions seem to come from the periphery. This was not work set out for viewing; this was storage, and apparently some kind of archive.

[circumambulate]

Ten years ago, Weslien was given the opportunity to walk to Lake Tara, known as the “Lake of Compassion,” with renowned Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman. Lake Tara, (also, Gauri Kund), lies on the path that circumambulates Mount Kailash in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Kailash is considered a sacred place in four major religions: Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism and Bön, and the Vedas refer to the mountain as a cosmic axis around which the entire universe turns. As abode of gods and goddesses, the mountain has been climbed only in myth (setting foot on its slopes is considered a sin), and the 52-kilometer trek to circumambulate the mountain travels from 15,000 feet through Drölma pass at 18,500 feet and back down again via Lake Tara. Nearby Lake Mansarovar is what remains of Lake Tethys (a Mesozoic ocean), considered the source of all creation. One of the highest sources of fresh water on earth, melt waters from the area feed tributaries that are sources of the Brahmaputra River, the Indus River, and the Ghaghara, a source for the Ganges.

Looking back on her work, Weslien has used water as a medium since 1997 when, in Nightlife, at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, she filled numerous tanks with water and found objects. As part of the exhibition, she collected dreams from the community. As viewers witnessed the transformation of the materials in the water over the course of the show, she felt there was a parallel process to the changing undercurrent of dreams in the community. Because of an ongoing interest in water as medium of transformation, the journey to the “Lake of Compassion” in 2006 held a certain resonance for her.

Water for many religions, and for Hinduism in particular, is a vastly important and sacred medium, attributed with great spiritual cleansing powers. Holy places are located on the banks of rivers and many rivers themselves are considered sacred purifiers. Every Hindu temple has a water tank where water is held for dry times, and water is used in rituals to cleanse mind and body. Devout practitioners collect water at sacred sites to bring back for home altars, and for those who cannot complete arduous pilgrimages. Water is a potent element for Buddhist practitioners as well, suggesting life and longevity and the power to wash away impurities. At Lake Tara, Weslien collected water and carried it home.

What does it mean to collect water from a sacred site and take it “out of circulation” — to put it into new systems of circulation and meaning, namely art? As she seeks to reveal the hidden and to ferret out some notion of truth, Weslien’s aims are not in contradiction with her counterparts who are collecting water for other (spiritual) purposes. She notes that the water becomes a conduit, a vehicle for meaning. When she returned to India, for example, devout friends who knew of her journey gratefully thanked her for bringing the water; they understood the hardships of the pilgrimage and where she had been. When she uses water in her installations the meaning is again transformed. The water from Lake Tara can be considered “water of compassion” and when one considers “what really matters” — a phrase Weslien repeats often — this notion of compassion becomes supremely important, and important to the meaning of the work.

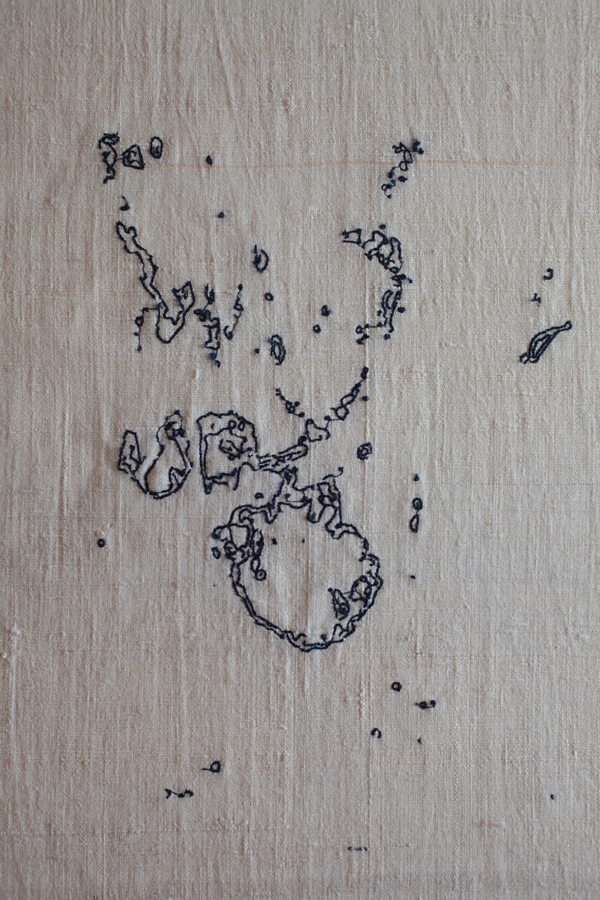

Since the 2006 trip to Lake Tara, Weslien has collected water from sacred sites in India and elsewhere. In 2012, while she was a Visiting Artist at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, she brought a microscope into the studio and began to investigate the collected water at a microscopic level. Quick to point out that she is not a scientist, Weslien was driven by the question “what is this water, what happens if I look at it differently?” Inherent in this and much of her work is a commitment to slowing down so that awareness is widened and deepened. Her investigation revealed patterns in the water (mineral or bacterial she doesn’t know), not unlike topographic maps of the mountainous regions where she collected it. Working with microscopic images of the water, she used digital processes to embroider these images as drawings in thread on hand spun silk fabric, called khadi, from the Ghandi ashram that she had collected on her travels. By bringing the water back and investigating it in new ways — drawing in close to understand it afresh — she translates this “water of compassion” to new forms, and creates new kinds of “maps” by which we may locate ourselves in the world.

In 2013 Weslien went to the Kumbha Mela, a festival held every 12 years in Allahabad, India. This mass Hindu pilgrimage, involving an estimated 120 million visitors over a two-month period to the site where the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers join, is considered the largest peaceful human gathering ever held. During the festival, pilgrims bathe in the rivers three times a day at auspicious times. It is said that bathing in the sacred water during the Kumbha Mela will cleanse a person of their sins. On the one hand, the water is pure and revered as a manifestation of the goddess Gaṅgā; on the other hand the water is polluted to toxic levels. This contrast is one that requires a certain negative capability to comprehend; both pure and impure, sacred and utterly profane, the river struggles under two ways of seeing that are currently disconnected.

Again, Weslien brought water home. And this water helps her engage new forms of seeing as she embraces the codes of her art process. Weslien had collected water near the source of one of the world’s largest watersheds, and met it thousands of miles later at a major confluence of rivers, and the water from the Kumbha Mela led to an installation, Confluence, that was shown at John Michael Kohler Arts Center in 2014. The installation paired the mesmerizing rhythm of walking in ritual pilgrimage with water from the Ganga and Yamuna in hundreds of vessels. Video taken while in Allahabad was slowed down and projected throughout the room, created a parallel slowing down, a kind of somatic shift, for the viewer.

[navigate]

Much like Roni Horn’s Library of Water, Vatnasafn, in Stykkishólmur, Iceland, which consists of 24 columns of water from 24 glaciers in Iceland, or like Katie Paterson’s Vatnajökull (the sound of) which allowed viewers to call a number to listen the sound of a glacier melting, Weslien’s project collects water and looks deeply into its potential as vehicle for multiple and layered ways of “seeing”. In particular, she is interested in slowing the viewer down so that they may see more, and see anew. Weslien notes that many artists are working with water right now. Looking at water pollution and water conflicts from Cochibamba to Palestine to Flint, recent resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline, and resistance here in Maine to the Nestle Corporation, it would seem necessity, and even desperation, is driving these investigations. Speaking of environmental concerns, Weslien points out, “Soon, all water will be sacred.”

Paradoxically, collecting can operate as a stay against loss — and indeed some of the sites she’s visited in the Tibet Autonomous Region are no longer accessible or are being transformed into singularly destructive tourist destinations by Chinese companies; widening roads, bringing in hotels and restaurants and creating for-profit landscapes on top of uniquely sacred ones. Archiving is a means to take stock of and record what exists before it’s too late, and art is one method for challenging invisibility — creating much needed visibility and attention around critical topics of our time.

**

For de Hoyo, the results were, in the end, disappointing; but it was not uncommon in places where water was sorely needed for zahorí, like their water-dowsing counterparts in Northern Europe, to appear. Necessity creates the conditions for new forms and new ways of seeing. Like the zahorí, Katarina Weslien wants to see under things. Suspicious of facile perceptions, her work asks the viewer to slow down; it demands a more nuanced gaze. Illuminating invisible substructures and belief systems, she regards the maps we use and helps new worlds emerge. In this new world, the artist’s job can be transformed into one of secular pilgrim, curious eulogist, voracious archivist, collector of water.

A new piece by Katarina Weslien inspired by these conversations, “Walking Kailash,” will be enacted in numerous cities this fall, including Portland, Maine. Stay tuned for more information from Platform Projects/Walks.

Swedish-born Katarina Weslien is a Maine-based multidisciplinary artist and educator. She is currently visiting faculty at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. www.katarinaweslien.com

- Swiderski, Richard M., X-Ray Vision, A Way of Looking, Universal Publishers, Boca Raton, 2012. p25. ↩

- Ibid, p26. ↩

- All quotations and comments are taken from a studio visit with Weslien on August 21, 2016. Any errors are the author’s. ↩

- Weslien’s research into textiles in the region and images of her trip are chronicled in the book Overland, 2011. ↩

- Author’s note: I walked to Muktinath myself in 1989, a few years later, another connection we discovered we share. ↩

Julie Poitras Santos is a visual artist based in Portland, Maine. Also a writer, her research interests include the relationship between site, story and mobility, and often involve areas where art and language intersect. She works as Director of Exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art.