by Kathy Weinberg

If Kathe Kollwitz, the German artist who died in 1945, was transported to the 1970’s and made a woodblock poster for the television show Charlie’s Angels — featuring actress Farrah Fawcett’s famous hairdo — the result would resemble Veronica Cross’s imagery from her recent body of work titled She’s (Not) There. The work calls to mind another artist, Joan Hassall, who was in her prime at the time of Kollwitz’s death. Her wood engraving images illustrated the peppery texts of Jane Austen’s novels in striking graphic compositions that made the hoop dresses and parlor manners of her women seem statuesque, and even imposing.

She’s (Not) There: The Re-Mix was recently at University of Maine Farmington Art Gallery. The exhibit asked the question, “What would it look like if the female figure were absent but her presence seemed tangible?”1 and goes on to make the assertion that “the conceptual ‘blank canvas’ of the figure’s vacant body is like a screen onto which we can project our desires.”2 But what else do we project?

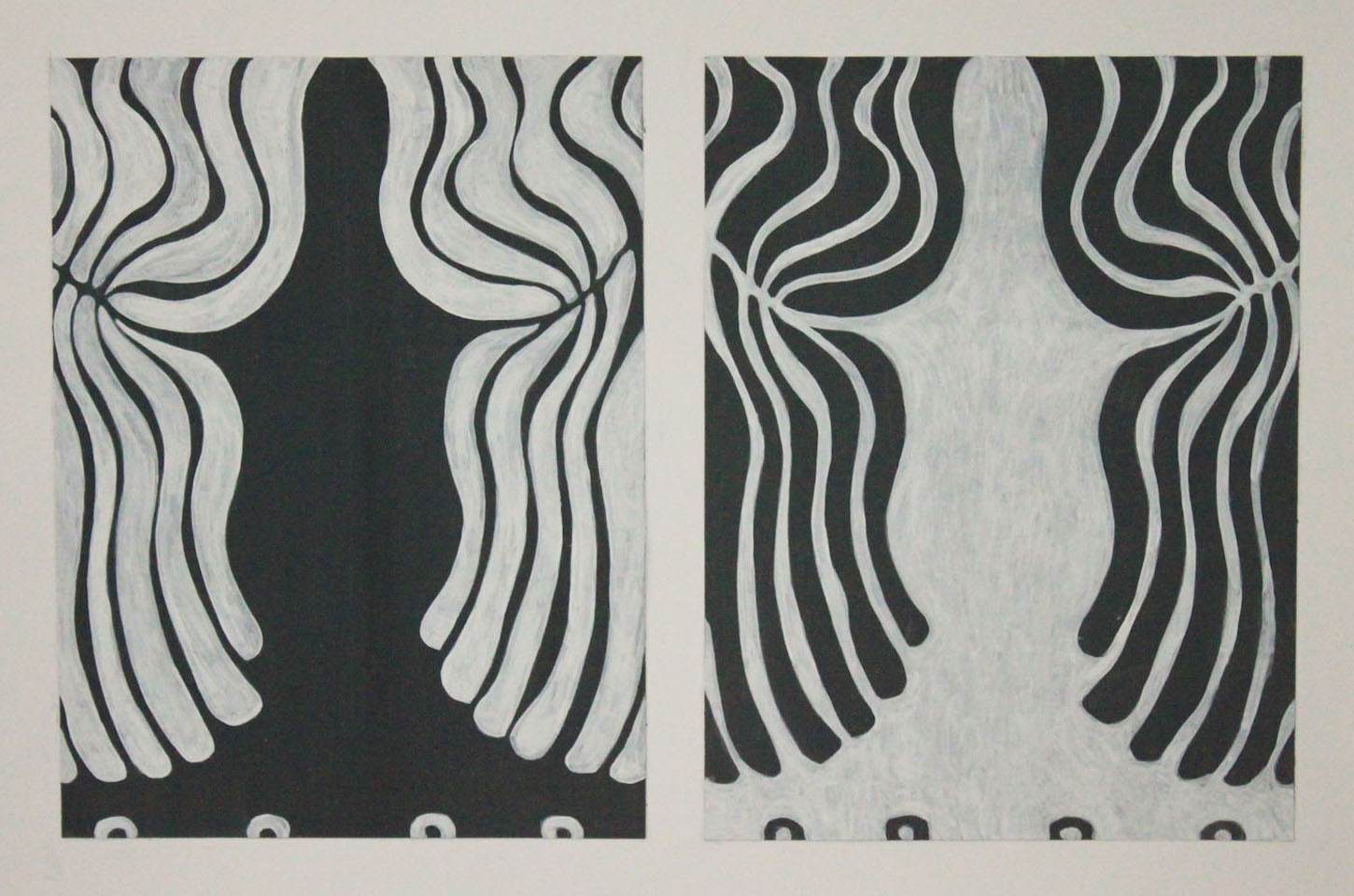

The women, hair, and theatrical drapes depicted in Cross’s black with white outline and “scratch” vocabulary combine with paper cutouts, and co-mingle with painted overlay and matte black casein paint mixed with gesso and plaster. At times they are idealized, approaching a stereotyped curve and proportion. But in Cross’ hands the images have a speed and ferocity that gives immediacy and a pop sensibility. Their imagery evokes graphic art, graphic novels, graffiti art, and Francis Picabia’s color paintings of black and white pin-up photos. The technique and style recall Willem de Kooning’s white on black and black on white paintings. The images are predominantly black and white, but the ideas, most certainly, are not.

With titles like Sirens and Headbangers, these women offer a danger along with the desire; they are the femme fatale and demi-goddesses. Cross’ show got its title from a popular 1965 song from the Zombies, “She’s Not There”. The lyrics are about a heartbreaker, a holdover from blues lyrics, foreshadowing the “bitches” and “hoes” of rap lyrics:

Well, no one told me about her

The way she lied

Well, no one told me about her

How many people cried

Well, let me tell you ’bout the way she looked

The way she acts and the color of her hair

Her voice was soft and cool, her eyes were clear and bright

But she’s not there

Like most rock lyrics the message is a simple story line that repeats itself and relies on the musical backdrop to fill in what is not said.

Cross’ figures resemble the rock lyrics, taken out of the music, or in her case the figures are often cut away from a background. That can make them timeless or turn them into a contemporary version of a black light poster, a genre of art that filled head shops and teenagers’ rooms in the 1970s, the era to which many of these images seem to belong. Cross’ women are counterpoints of the women who float through the opening credits in James Bond films, where silhouettes writhe across the screen as objects of desire. The pop/vintage images she has lifted from are companions of blacksploitation flicks such as SuperFly — bordering on a caricature of femaleness. Silhouette art, a popular Victorian era genre that illustrated cut out figures and profiles, often contained in lockets, is regaining a place in contemporary art, seen in recent works of Kara Walker; Cross alludes to this genre but at times reverses it like a photo negative.

There are several images, Swishy Britches, Doppelganger I, and Double Exotica where Cross doubles and reverses the positive and negative grounds and outlines, white becomes black and black becomes white. The patterning of foliage, feathers, and curtains carry a strong rhythm of flowing lines and design. These double images create a transformation: the content is altered, the iconography becomes pattern, allowing new associations. By using imagery of women that sets the clock back to the 1960s and ’70s, Cross evokes a dynamic era of nascent radicalized feminism. The stereotypical American Family was breaking down and more women from the middle class entered the work force.

Examining and exploring changing feminine roles is not the exclusive territory of woman. In the 1974 Martin Scorsese film, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, actress Ellen Burstyn sings, in an apologetic voice, with a tight-curled hairdo (not the more chaotic, liberated locks that Cross depicts in works like Coil) that mirrors her insecurities in the virtually all-male bar scene where she auditions — recently widowed and entering the job market as a singer. This is a pivotal moment, of a woman entering the stage, and of a woman emerging from the background to take the spotlight. The scene, created by a male director, gives us a slow pan of a blank-faced male audience and we can empathetically share Burstyn’s anxieties. The counterpoint female lead is the young Jodie Foster, a flat-chested tomgirl, with short, un-styled hair, unafraid of shooting off her mouth, and drinking ripple wine. Like the character played by Tatum O’Neil, (also with “boys'” hair) in Paper Moon, these are wise young girls with the sharp wit of screenwriters who have studied English literature, and know the writing of the 19th century author, Jane Austin. These pre-pubescent girls represent a new model for female power, the tomgirl, an Amazon who could compete in a man’s world by relinquishing their feminine attributes. The timid Burstyn character got the job but her passive theatrical type later gave way to a new generation of powerful, female forward, pinup pop stars like Deborah Harry, Madonna, and Beyonce. These new stars combined their pinup glamour with a sense of pride, and the confidence of ownership. Each one could be picked out in a lineup just by their hair.

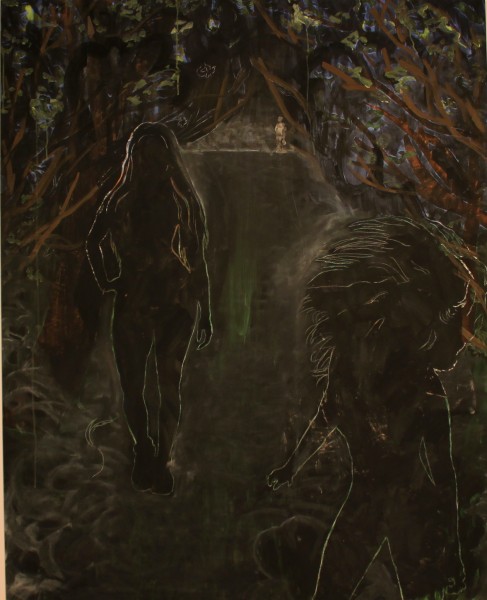

Cross is aware that her women and floating hairdos are not mere images — they are signifiers, iconic as a corporate logo. She claims to have “hijacked” images from popular culture and some vintage sources, but have they in turn hijacked her message? The borrowed images come with suitcases packed with associations. Some of the associations are humorous as in Nature GRRRL, where a pin-up silhouette primps in the verdure, many years after Manet’s provocative Dejeuner sur l’herbe, (1863). Cross’ women are powerful, desirable and dangerous, badass all. They are Wonder Women, Divas, or, as in Crown of Glory, recall Mary Magdalene’s robust, yet penitent hair as envisioned by Donatello. But what are these women’s other attributes and how do they play off the inhabitants of their world? Is there a Zeus to pair with her Heras?

Roland Barthes in his Mythologies, writes about the difficulties in pinning down meaning (of an image) through reference. Every image carries with it multiple meanings and stands for new concepts as the generations pass the icon along. Cross presents her women but what are we to make of them? Heads of hair evoke wigs, then scalps, or transform into Medusa, locks of hair become feathers. Then, as we step closer to examine the images, they break down into paint and line and paper. We go to look for her, but she is not there. In Grande Dame, a related work not included in the show, the house lights are up, the curtain is open but there is no one in the spotlight. Perhaps this would be the place for the famous cutout teeth of Willem de Kooning’s Woman I: the collaged teeth were later removed and replaced with painted, ferocious teeth. In the case of Grande Dame it would give us the smile without the woman — a Cheshire girl. But perhaps the missing woman, the curtains and trappings are all reminders that this is theater, the myth of the glamour is fabricated, subject to decay, ripe for misinterpretation and reinterpretation. All is allusion and illusion — all is vanity.

In order to create a new art and recreate the image of women, one needs to examine and understand the evolution of women’s roles and of the differences between the middle and upper classes and the working classes where social change evolves at different rates and under different circumstances. In the painting Manifest Destiny, a woman in a model’s pose looks off into the distance, away from the viewer, but what destiny does she envision? The title is a key to the idea of a woman’s body as a territory. This suggests the female body is simultaneously property, sovereign nation, and even sacred ground.

When Cross alludes to a cutout female figure from an era that was giving birth to dynamic social change, she has cut away the background but cannot remove history. And yet She’s (Not) There does succeed in doing that, casting these images out into a dark night to survive or perish on their own merit. Perhaps true equality in the future will not be a reaction, an opposition, to the (repressive) Victorian era of “women and children first,” with the chaos of “everyone for themselves,” but could become “May the best selves win.” At last! We achieve equality, adrift in our lifeboats, floating in the dark of a poster painted night.

Veronica Cross‘ She’s (Not) There: The Re-Mix ran at the University of Maine Farmington Art Gallery from October 15 through November 15, 2015.

Kathy is an artist and writer living in Morrill Maine, just outside of Belfast. Her poetry has been published in Off the Coast Literary Journal, The Island Reader, and she was one of three winners in the Maine Community Foundation essay contest, A Place in Maine, in 2013. Kathy is also an artist working in a variety of mediums including painting, sculpture and photography. She has exhibited her work in New York, Germany, and Maine. Her profession in antique and architectural restoration includes museum period room installation projects at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Museum of the City of New York, and private residences and collections.