by Andy Johnson

As is un-ironically true of the entire art historical canon, (white) men often dominate the narrative of artists who utilize bodily fluids (and solids) as a medium — urine, semen, feces, tears, flesh, saliva, and blood. Contemporary examples include Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, Vito Acconci’s Seedbed, and Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle, to name a few. To counter such narratives, Transformer, a Washington-DC gallery space, recently presented the exhibition Bloodlines. Curated by Martina Dodd and consisting of all female-identified artists, the exhibition explored the social stigma surrounding menses, blood, reproduction, and the feminine body, while underlining the intrinsic power both women and the reproductive body hold.

While the exhibition is no longer on view, my focus in this review is to call out and name the systems of white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and misogyny/misogynoir that Bloodlines critiques. As such, it is critical to note that while conceptually centered within a female framework, the exhibition lacks a clear analysis of the term “womanhood”. Where do women who were born intersex, trans women, or women who — for one reason or another — do not experience menstruation or who cannot reproduce, fit? All this to say, how can we challenge the cissexism of the term “female”, and in ways that confront heteropatriarchy, misogyny, and transmisogyny? I seek to underline the ways in which these hegemonic systems intersect and empower one another to maintain the hierarchy of value placed on the feminine body.

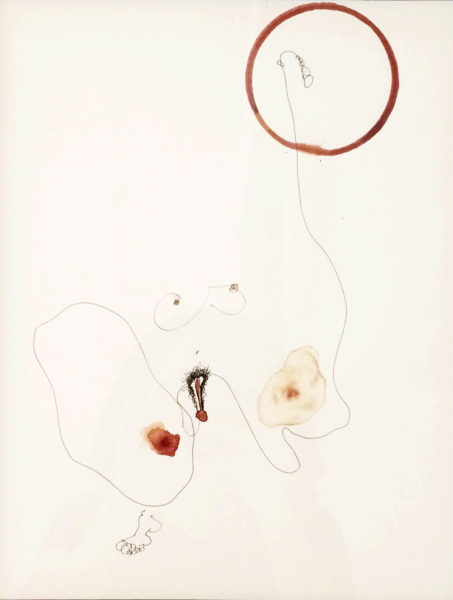

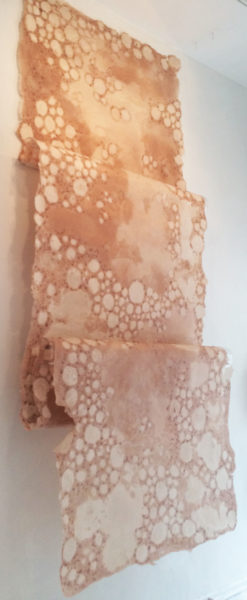

Artists Iman Person, Samera Paz, and Lisa Hill reflect upon menstruation and the reproductive cycle through works on paper. Person and Paz utilize their own menses in the production of their abstracted works. Person allows the blood to soak into the paper, highlighting particular areas of her abstracted figures, while Paz photographs and scans the movement of her menses between two glass plates. Lisa Hill’s large-scale installation cascades from the ceiling, alluding to the shedding, scarring, and regeneration of human skin cells every 93 days. While not a direct reference to menstruation, as in Person and Paz’s work, Hill’s process illustrates human genealogy on a larger scale. The work serves as a mapping device, alluding to ancestry and bloodlines as timekeepers and record keepers. The shrinking and disfigurement of the paper is evidence of a cell’s multiplication, a process that is vital to both life and reproduction.

Beyond the aesthetics and formalist aspects of blood on paper, it must be noted that the gesture of including one’s own menses and making reference to the power that the reproductive body holds is bold in our current political climate. To claim one’s own body as a site of resistance and make visible the intellectual, emotional, and physical labor that it requires to navigate hegemonic systems of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy, is critical. In a late capitalist system that rewards and acknowledges groups with the most profit and monetary value, it is essential that we recognize the importance of emotional and intellectual labor, the kinds that are so often belittled and made invisible: self-care, self-worth, and knowing that no matter what society tells you, you are your greatest source of power. As independent feminist scholar and writer Sarah Ahmed notes in her post “Selfcare as Warfare”, “when you are not supposed to live, as you are, where you are, with whom you are with, then survival is a radical action; a refusal not to exist until the very end; a refusal not to exist until you do not exist. We have to work out how to survive in a system that decides life for some requires the death or removal of others.” Person, Paz, and Hill offer legitimacy to the collective strength of women, when so often our social reality is characterized by a refusal to acknowledge women as human. (If you disagree, please refer to the recent healthcare bill introduced by the House and Senate, the relentless threats and attacks on Planned Parenthood, the nearly constant reports of trans women of color being murdered, the President of the United States of America’s plethora of disparaging comments about women’s bodies…)

It was Audre Lorde, the self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” who dedicated her career to naming and emboldening the power of a woman’s emotional and intellectual labor and revealed the inherent power that exists when one occupies the margins. Tsedaye Makonnen’s performance The Crowning was a meditative reflection on the words of Lorde. As Makonnen entered, she sprayed the room with rosewater. Six participants were crowned with pelvises wrapped in black tape, while each viewer held a single continuous red string in their hands. As the six participants surrounded Makonnen, she stood atop a white pedestal reading select passages from Lorde’s seminal text, Sister Outsider. To conclude, each participant tipped their crown, spilling red candy and chocolate on the floor, while the viewers indulged in communal red wine. Ingeniously, Makonnen activated Lorde with a complete sensorial experience — sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell. The social and political stigma of women’s bodies, in particular women of color, relies on secrecy and shame. Makonnen’s performance served as a direct challenge to the discourse of humiliation and indignity that characterizes a woman’s sexuality and subjectivity, effectively lifting that veil of silence. The Crowning critiqued the systems of power and value that seek to disparage both the female mind and body; it offered humble solace to those who often find themselves constantly battling against a heteropatriarchal and racist regime.

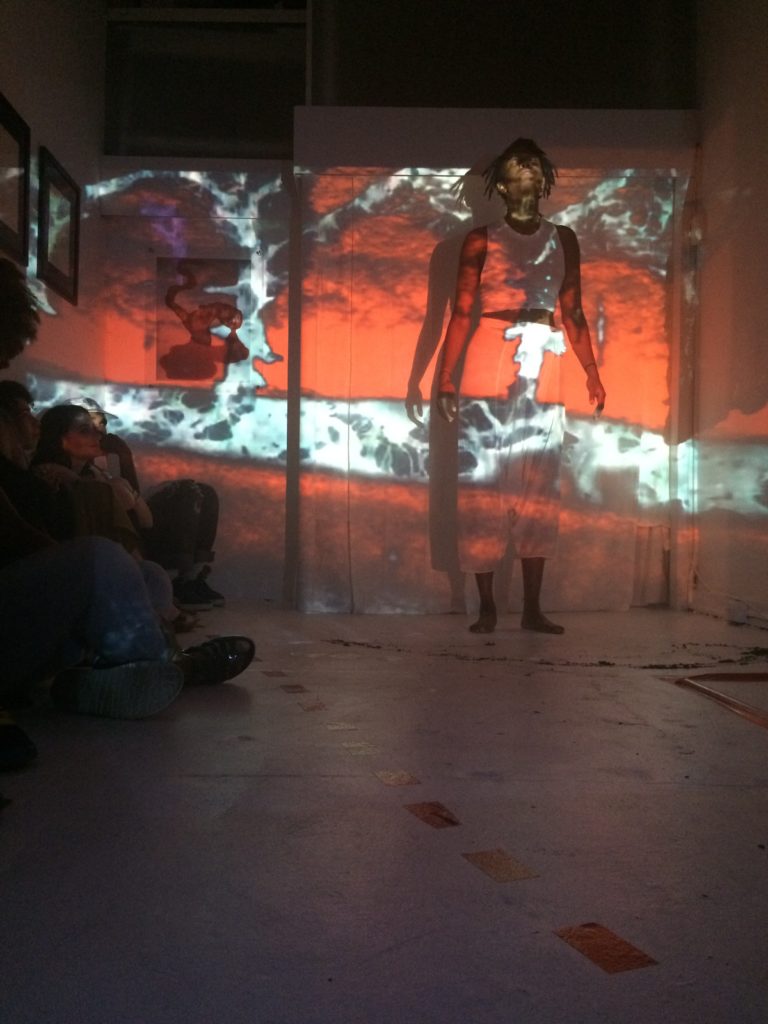

The exhibition’s second programmed performance, Cosmic Meditation, offered viewers a combination of dance, video projection, and spoken word. Presented by the àjé collective, a queer Black trans-media exploration of the erotic complexities of menstrual blood, the performance focused on the parallelism between the cycle of the moon, the menses cycle, and one’s own body in relation to a larger network of cosmic energy. The performance prompted the viewer to ask, “What can women achieve when they embrace that which society finds most grotesque, most undignified, and most deplorable (i.e. their own bodies)? What is a woman capable of when she realizes that her strength resides not in pleasing others, but pleasing herself?” As Lorde points to in her critical text “Uses of the Erotic”, “recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama.”

Bloodlines serves as a double-edged sword: one side critique, the other healing meditation. Few honest spaces exist to collectively gather and recognize the power and legitimacy of emotional and intellectual labor. Within those spaces, to name the forces that seek to destroy you is radical, but to embody and proclaim solidarity to the thing with which society oppresses you is an act of self-preservation.

Bloodlines ran at Transformer in Washington, DC, from May 20–June 24, 2017. Images courtesy of Transformer and Martina Dodd.

Transformer

1404 P Street, NW Washington, DC | 202-483-1102

Open Wednesday through Saturday, 12pm-6pm, during exhibitions and by appointment.

Andy Johnson is a DC-based art historian, arts writer, curator, and currently director of Gallery 102. His academic and curatorial practice centers on queer, feminist, and black feminist theories, critical race theory, cultural studies, photography, video, performance art, and visual culture. He holds an M.A. in Art History from The George Washington University. He has presented research and spoken on panels at universities and museums including Rutgers University, University of Georgia, UC-Santa Barbara, GW, Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts, and GW Museum. He is a contributing editor at DIRT DMV and has curated exhibitions for Gallery 102 and DC Arts Center.