by Skye Priestley

A pair of shows at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art trace our understanding of night from the mid-19th century to the present day.

Night Vision: Nocturnes in American Art, 1860-1960, has been widely anticipated as the first major examination of the night in American art. Night Vision is encyclopedic without being enormous: in five small galleries we examine the night through a variety of media and historical viewpoints. Among the artists represented here are figures of importance, some with connections to Maine, like Hopper, Homer and Hartley, Marguerite Zorach and Andrew Wyeth.

From a multitude of movements come a multitude of themes. From the Hudson River School we have Albert Bierstadt and George Inness. The closing of the frontier and the mythologizing of the west? Here is Frederic Remington. Childe Hassam represents American Impressionism, Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz cover the development of photography and Ansel Adams its extension into the mid-century. The Ashcan School, early American Modernism, the Harlem Renaissance, and Abstract Expressionism are also represented. The effects of electrification are of particular importance, but older, mystical representations of the night as a time of reverie — either spiritual or hedonistic — are not far behind. Because many of the artists worked in or around New York City, the city-scape features prominently. So, predictably, does the moon.

A Waterfall, Moonlight, from around 1886 and by Ralph Albert Blakelock, could have been plucked straight from the easel of a German Romanticist. The black silhouette of a large tree broods eagerly over a river. The moon, placed behind the tree, struggles to pierce the darkness of its branches. In the foreground, a waterfall tumbles into the surrounding indistinguishable morass. Blakelock was a fiercely independent artist and he captures a night that is both beautiful and sinister.

In the face of so much that is significant, the works of minor artists tend to arrest the attention. Martin Lewis, who instructed Hopper at one point, has several excellent works that exceed expectations. Which Way?, an aquatint from 1932, shows a car stopped at a winter crossroads, its headlights illuminating a single telephone pole directly in its path. The work is so finely illustrated, from the lumpy smoothness of the snow bank to the spindly iciness of the frozen trees, that it’s immediately familiar to anyone who has ever found themselves lost on a country road.

…it can be difficult to determine whether the invasion of our collective privacy is an outrageous affront or merely the inevitable byproduct of an increasingly ubiquitous technology.

Night is the best time to see without being seen. Night Vision features several works that might be considered voyeuristic. The most significant of these is John Sloan’s Three A.M., a 1909 canvas which considers two women living in a New York apartment. One has just returned from a night shift, while the other has just arisen. The picture was based off of two women whom Sloan believed to be sisters and observed from his window. While Three A.M. has historically been considered an important portrait of working-class women at a time when few artists focused on such subjects, the notion of a painter capturing our images without permission may strike some viewers as off-putting.

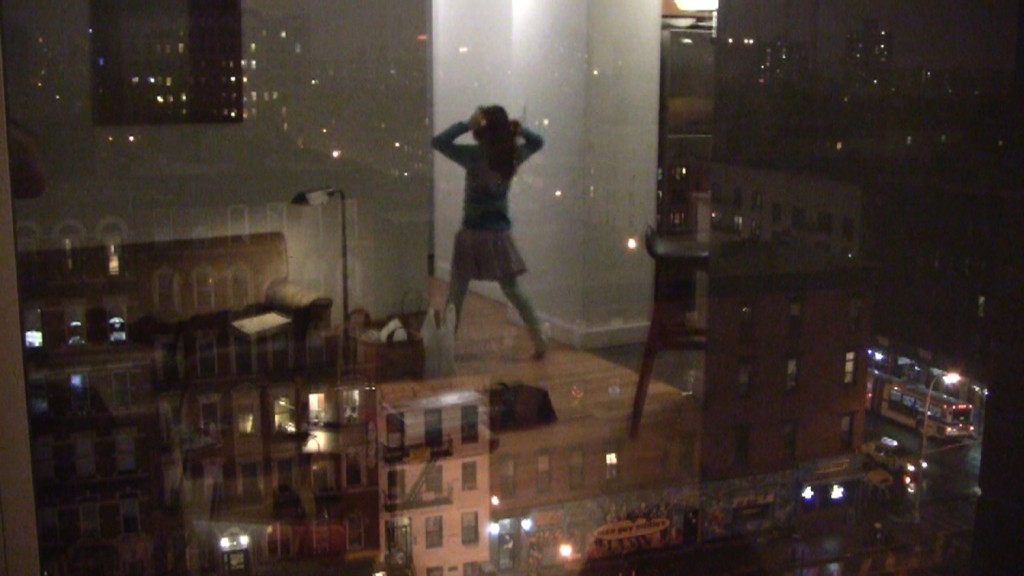

Creating art based on clandestine observation remains controversial today, an issue further agitated by the video installation by French artist Michel Auder, Untitled (I Was Looking To See If You Were Looking Back At Me To See Me Looking Back At You). The work features three screens that show separate fifteen-minute loops. All of the material was filmed from the artist’s New York apartment. Two televisions content themselves with examining the rising moon or the movements of cabs on a snowy evening, while a projector shows images of tenants living in the apartments opposite Auder’s.

Because the camera never lingers too long we are mostly treated to small vignettes from the lives of Auder’s neighbors. Two men change a light bulb, a woman smokes a cigarette, people use computers, blow dry their hair, cook, undress, watch television, walk around, lie in bed, have sex. A soundtrack accompanies the images: a constant whispering that could almost be conversation intermingles with an assortment of music. The music intermittently grows louder before abruptly subsiding. The soundtrack is altogether similar to the aural landscape of a crowded sidewalk.

While its flowery subtitle might be enough to give offense, whether Untitled actually crosses boundaries of decency or not must be decided by each individual viewer. In an age of NSA wiretapping and “the right to be forgotten” it can be difficult to determine whether the invasion of our collective privacy is an outrageous affront or merely the inevitable byproduct of an increasingly ubiquitous technology. In comparison to George Orwell’s dystopian vision of a lurking authoritarian government, bystanders today are more likely to fall prey to the efforts of overzealous advertisers poaching our browser histories or, as in this case, of video artists recording our every moment for inclusion in meditative art pieces.

Michel Auder:Untitled (I Was Looking To See If You Were Looking Back At Me To See Me Looking Back At You) continues through October 18, 2015 in the Media Gallery.

Night Vision: Nocturnes in American Art, 1860-1960 continues through October 18, 2015 in the Halford, Center, Becker, Focus and Bernard and Barbro Osher Galleries.

Bowdoin Museum College of Art

9400 College Station, Brunswick, Maine | 207-725-3275

Open Tuesday–Saturday 10am–5pm, Thursday 10am–8:30pm, Sunday 12pm–5pm through October 18, 2015. Free.

Skye Priestley is an artist, poet and critic living in Portland. He likes to play soccer and ride his bike. You can find some of his writing and artwork at sjpriest.wordpress.com.