by Meg Hahn

Announced as a MacArthur Fellow in 2015, and now with concurrent exhibitions in New York City where she lives and works, Nicole Eisenman has had a successful year thus far to say the least. Al-ugh-ories, presented by the New Museum, and Nicole Eisenman by Anton Kern Gallery, provide full and varied looks at Eisenman’s oeuvre. While both exhibitions feature samples of sculptures and works on paper, Eisenman’s paintings are the strongest by far, containing an intellectual and formal awe. The discourse they offer around painting itself, in addition to contemporary issues on politics, sexuality, and daily life, is translated through her strength in technical craftsmanship.

Al-ugh-ories serves more like a retrospective, with works spanning from 1996–2014. Viewers can visibly trace her artistic development, as the paintings here show the evolution of Eisenman’s interest in producing narratives that appear humorous and a bit illogical, but at their core, portray relatable settings and emotions. Emphasized by the show’s title, Al-ugh-ories connects ideas of humanity through the symbolisms in her paintings, where she builds familiarity through the depiction of the figures and choice of objects. Frequently painting scenes like a beer garden at night, canvasses are filled with figures captivated in their own worlds that represent the range of human emotions and dimensionality we all contain. There are masses of tired-looking patrons and employees, a few couples dancing, one sharing a kiss, a woman lighting a cigarette about to engage in conversation, and a man closeby seemingly taking notes with the figure next to him. The density is a reminder of places we’ve all been, where — despite the claustrophobic nature — we still go. Like the Impressionist paintings by Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec of bars and parties of the late 19th-century, Eisenman contemporizes this scene of socialization. Rather than showing groups of people all with wide smiles enjoying themselves, she portrays morosity, joy, and contentment: feelings in others and ourselves that are more realistic to how people really function.

Using less of a chronology and thematized connection however, Anton Kern’s show is solely a debut of new works, focusing more on the extraordinary feats these paintings are. These works demonstrate her multiple approaches to depicting scenes like sitting on a train to being with friends inside an apartment. As the press release describes, the focus is more on the internalizations of her daily life, specifically through the lens of being a queer female New York painter.

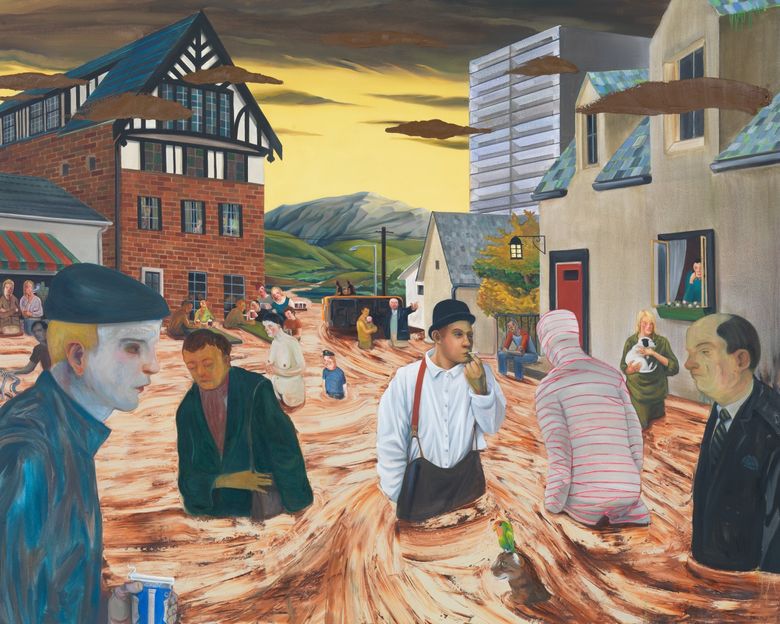

The variances in Eisenman’s techniques, both nuanced and bold, portray her strong ability, knowledge, and integrity to the discipline of painting. The longer one takes in carefully viewing these paintings, the greater the reward. Her vast catalogue of gestures and marks nod to art historical referents like Edvard Munch and Paul Gauguin. She demonstrates a confidence in the material, harmonizing paint squeezed directly from the tube alongside soft academic rendering. In Coping, for example, the burnt sienna-like water the figures are trudging through accumulates a slight thickness in paint, looking like the gestures of a palette knife, while the bodies vary in color and style, appearing effortless and natural. Moreover, most of these works are fairly large in scale which contribute to the viewer’s ability to become encapsulated inside Eisenman’s world. The figures being roughly life-size add to the relatability of the portrayed circumstances and emotions. Through demonstrating a range between geometric abstraction to more representational, she combines these dichotomies creating styles that are unique to her, rather than sticking to the limitations of one.

While the New Museum focuses on the allegorical nature of her paintings and Anton Kern on her daily life, what strongly bridges these shows and works together is the diversity in how the role of intimacy is portrayed. The intimate relationships between: Eisenman and her practice, academically and technically; the figures in the paintings, which seem very autobiographical; and the paintings and the audience, perceptually and in the vulnerability of exposing her personal life and ideas.

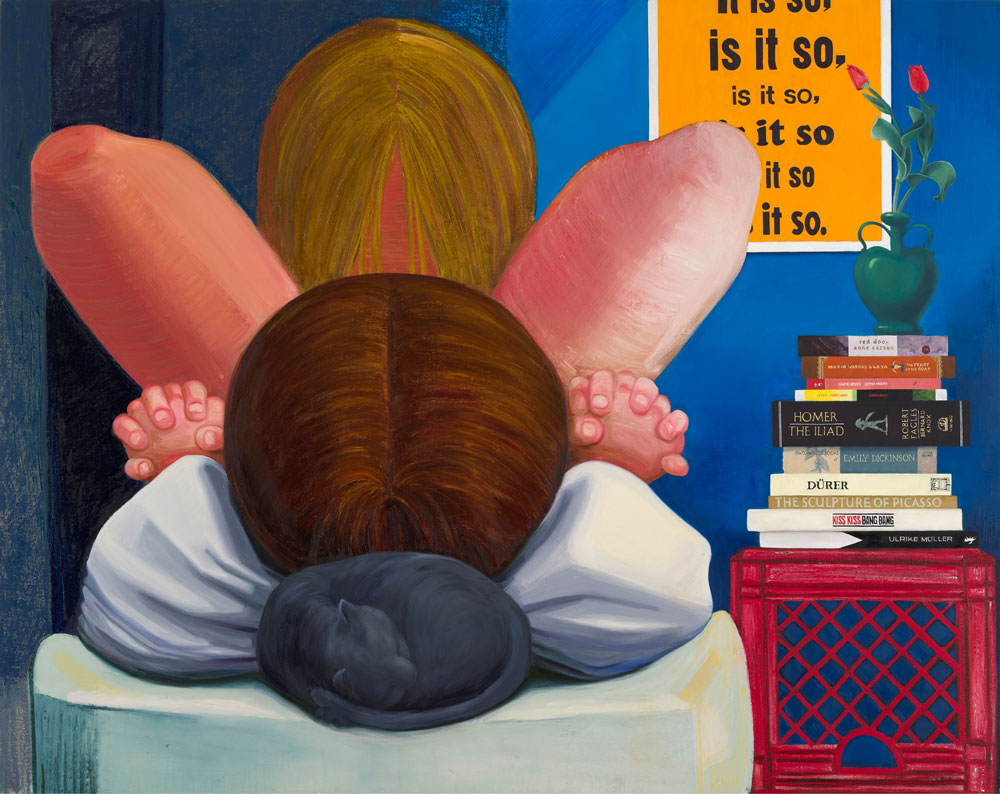

As stated earlier, Eisenman’s dedication and genuineness to painting and its history are apparent. In person especially, they emit a sense of care, thoroughness, and attention. They provide an emotional response that displays a deep connection she assumedly has while creating her work, being diligently devoted to her artistic development. Besides the closeness Eisenman has with her practice, the figures she creates are many times in intimate positions themselves. The recent work, Morning Studio, shows two female figures, one topless, together on a makeshift futon in the comfort of a humble apartment, the projection of an Apple computer screen behind them. As the clothed figure stares directly at the viewer, her expression shows a tough demeanor but acknowledges the private moment she’s allowing you into. Even the default computer screen background and the milk crate with the tuna fish can on top feel like important inclusions. These moments of humbleness and familiarity strengthen the piece as these small details reveal parts of herself. Depicting a moment that shows the lives of those she is close to or a representation of a relationship of her own, nonetheless address Eisenman’s world.

Furthermore, there is an intimacy between the viewer’s interaction with the work, and Eisenman’s authorship in what she divulges. As her paintings have an openness in sexuality, they provide us with a private view into her life. As stated in a recent New York Times interview, “Work comes out of life…Being a queer woman is the air that I breathe, and it’s inescapable, and it’s going to be part of the work.” The paintings Eisenman creates are therefore a reflection of her personal life. They are intimate through the process of making and the ultimate image itself. Uncautious, she exposes experiences and viewpoints from her life that have a serious and humorous tone to them. These private intimate moments put the figures in the work and the artist herself in a state of vulnerable critique.

While visiting these two exhibitions, I also considered the role of audience accessibility. While the New Museum caters to attracting visitors of all kinds, for Anton Kern, casual walk ins are more of a secondary concern. Thus, these exhibitions display different kinds of viewers and perhaps publicity. As some of Eisenman’s strongest paintings are at Anton Kern, does the location of being in Chelsea, a highly affluent and influential spot for the distribution of contemporary art, make the paintings more intimidating or exclusive to be viewed in comparison to the reception the New Museum will receive? Or rather, is it the institutional format of a blue chip gallery over a public museum?

If only able to see one show, both are certainly impactful. Besides the visual fodder these paintings contain, they offer rich discourse and commentary on contemporary American culture regarding sexuality, politics, technology, and history. Eisenman isn’t afraid and finds it important to address these complexities we face as a society. Her paintings demonstrate the value in taking time in being with a work in person.

Al-ugh-ories was at the New Museum May 4–June 26, 2016. Nicole Eisenman was at Anton Kern May 19–June 25, 2016.

Meg Hahn currently lives and works in Portland, Maine. She graduated from Maine College of Art with a BFA in painting and a minor in Art History. Meg was a finalist for the Joseph A. Fiore Painting Prize (Damariscotta, ME), and has attended the Vermont Studio Center (Johnson, VT), Hewnoaks Artist Colony (Lovell, ME), the Monhegan Artists’ Residency (Monhegan Island, ME), and will be a resident this summer at The Sam and Adele Golden Foundation Residency Program. She is also interested in other forms of art practice including curation. Meg is a co-director at Border Patrol (Portland,ME) and works out of the SPACE Studios building.