by Jacob Fall and Virginia Rose

Around 1595, Denys Calvaert, a Flemish painter living in Italy, painted an Annunciation that is now in the collection of Bowdoin College. In 2015, Elise Ansel, a painter living in Portland, saw this piece of late Renaissance devotional art and found it to be fertile ground for her own work. In the catalog for the exhibition (which is free, by the way), Ansel writes: “I make paintings that are derived from Old Master depictions… . I use painterly notation and shorthand to translate historical art into a contemporary pictorial language.” Jacob Fall and Virginia Rose recently visited the Bowdoin College Museum of Art to discuss Ansel’s Distant Mirrors.

Jacob Fall: Calvaert’s Annunciation, done in oil on copper, is a fairly small painting, about 21″ by 16″. Mary stands on the right, a few steps back into the painting’s space. She wears rose and blue. The angel Gabriel kneels in the lower left foreground in a brilliant white robe with a bright red sash. He points heavenward, and God leans out of the sky with a bestowing gesture. He uses his left hand — sinister! — and the ochre glow around it made me think if Zeus turning himself into a shower of gold to impregnate that nymph…

Virginia Rose: Danae; another kind of immaculate conception. This is a great painting: classic Renaissance pyramid composition with subtle detail and traditional symbols.

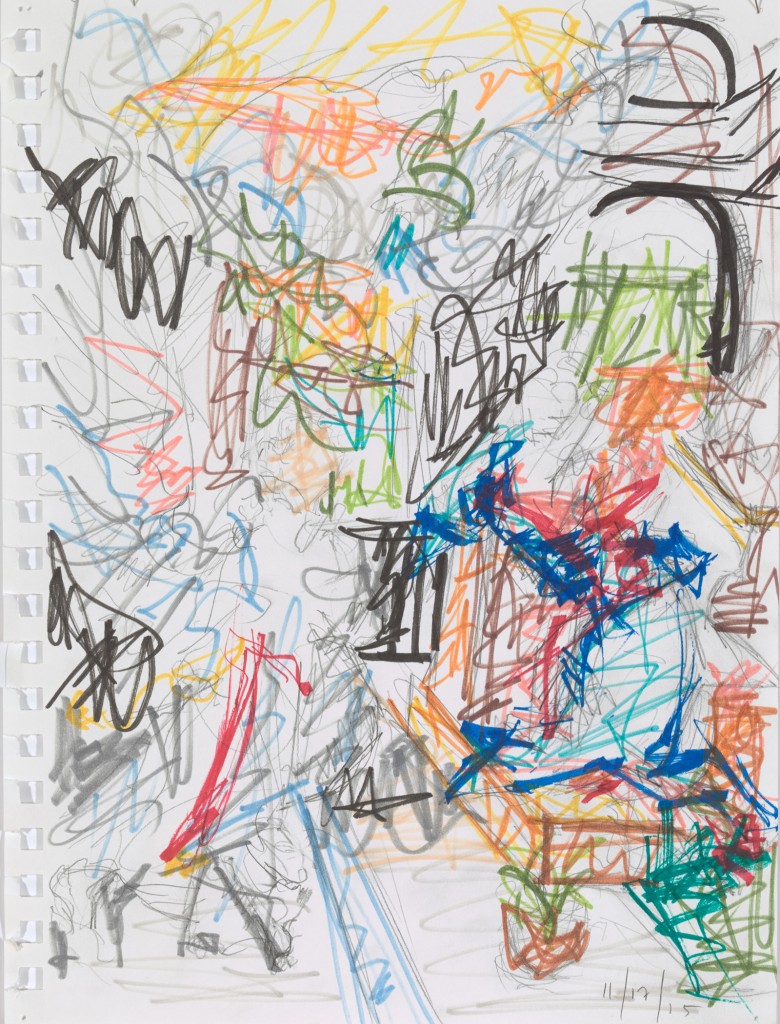

JF: We’ve got nine oil paintings by Ansel and seven drawings that she made in the mornings before starting to work on the paintings. All of this work was done in a few weeks during the fall of 2015. The paintings become increasingly abstracted as they go along, increase in size though the seventh, then shrink. The drawings help to reveal Ansel’s thought process: what to emphasize, what to leave out. In the first, the angel’s head becomes a mass of light brown hair and the Virgin just a cluster of pink and red strokes. God disappears, leaving only a trace of his left arm, and the sky looks like a sunset. In the second painting, Gabriel has lost his head but his wings are still painted realistically (if you believe in angels). By the seventh one, the red sash and wings are gone and the Virgin is reduced to a bloodstain.

VR: I like that the paintings are called Revelations. I think this suggests Ansel’s personal revelation concerning her process. The painting and the process are fun to follow, rich, and intense. That vase of lilies in the foreground, a symbol of purity disappears early in the series, eliminating the symbolic purity. I don’t need a theoretical dialectic to enjoy good painting. She’s a painter’s painter. That alone is frankly enough.

JF: You don’t find many places where her brush seems to hesitate or where she overworked something. The paint is juicy but not runny. Ansel makes pictures that convey a sense of objects in space without using the illusions of realist painting. She works from historical models but the results aren’t trying to convince you that there is anything there beyond paint on a surface.

VR: Ansel is breaking down a sound composition, ripping it apart, failing miserably, then rediscovering it in quick succession — this is the process of good painting made visible. In the seventh and largest painting she’s gone too far: that welter of white strokes unbalances the painting. Then she goes back to smaller size and turns the image upside down.

JF: In her lecture the other day, Ansel said she does this to empty the image of its narrative content.

VR: …and she changes the composition from a pyramid to an X — so much is resolved here. These last three paintings are great, number ten is fantastic! She is problem-solving the issues of perception and interpretation right on the canvas. The artist’s statement in the catalog is more revealing; I like how she compares her process to Comparative Literature. In her statement, Ansel writes about the move toward abstraction: “Linear, rational readings are interrupted…” Yes! I appreciate these works more as responsive painting than critical text. The final paragraph of her statement helps you understand [exhibition curator] Hanétha Vété-Congolo’s complex essay in the catalog, when Ansel mentions the “toxic consequences of an uncritical ingestion of the plethora of images of ‘beauty’ with which we are confronted on a daily basis.”

JF: In his famous essay, “Modernist Painting,” Clement Greenberg said that using a medium’s essential aspects to critique the medium itself was central to Modernism; Ansel uses the techniques of postwar painting, specifically gestural abstraction, to critique the social structure of the Renaissance by riffing on the tropes of the era’s painting. She writes [in the catalog] of wanting to portray female experience “from the inside out.” We could imagine that for her the crimson of Mary’s robe refers to menstruation and childbirth, but maybe I’m thinking of Mary Kelly’s or Greta Banks‘ work. Ansel’s approach to the historic painting she starts from is explicitly feminist: working “in a female voice”; and reacting against the objectification of women. There are many binaries here: historic-contemporary, male-female, representation-abstraction, and we could go the full deconstruction route and talk about social constructs, implied hierarchies, power relations…

VR: I am taking on the devil’s advocate position here. Certainly women had very little power and authority in the Renaissance and Ansel is taking on the past in a general sense. And she chose a fantastic painting to riff off of. But in many ways, I think seeing women as “objects” is much more of a 19th century idea (the Cult of True Womanhood, the domestic angel), which presents some interesting problems: a feminist take as an afterthought upon reflecting on the painting. Objectification has taken place on the part of the artist here (Ansel), making Mary an object from which to work like a still life, translated through a painting lens that removes the spiritual in favor of the formal.

In our current conflict-ridden world, Ansel’s thoughts as manifested by her art production process and concrete body of painting, singularized by unpredictability and life-giving colors, are as relevant as they are revivifying.Hanétha Vété-Congolo

Historically, with this source material, I also find this objectification problematic on other levels: the cult of the Virgin and its importance for the Counter-Reformation (Calvaert is a Flemish artist who moved to Italy), the private devotional aspect of the source material, the role of women in general. Women artists were quite prevalent in Bologna at the time: Elisabetta Sirani opened a school in the early 17th century and there were about two dozen women artists known to be working in Bologna in the 16th. In Ansel’s statement about depicting the female experience from the inside out, I guess I’m just not seeing that in the work itself. In the catalog there is mention of Ansel choosing work from a period in European history when women were considered “other” — honestly, I would argue that that period never ended, as evidenced by the current political climate of the US. Interpreting the essay in the catalog, for Ansel to be re-visioning and re-presenting a work from this past would posit Calvaert as specifically creating a work of art that is about objectification, which is faulty: Calvaert’s work is more of an attempt to make visual the central mysteries of Christianity. Yes, she is examining art of the past to make a new vision that neutralizes the source, and yes, it creates a new “fable” through a different lens and painting technique, but the true power of this rests with the art itself as a feminist reinterpretation of an old master.

JF: Would this show be less intelligible if all the wall texts were taken down?

VR: No, this work is really about painting and process and problem-solving on the canvas.

Elise Ansel: Distant Mirrors continues through April 17, 2016.

Bowdoin Museum College of Art

9400 College Station, Brunswick, Maine | 207-725-3275

Open Tuesday–Saturday 10am–5pm, Thursday 10am–8:30pm, Sunday 12pm–5pm through October 18, 2015. Free.